Ebola, dengue, yellow fever: Paper-based test will give diagnosis in minutes

Scientists have developed a paper-based test that changes colour and can give a patient a diagnosis within minutes on whether they have Ebola, yellow fever or dengue. The test is ideal for developing areas as it requires less resources than polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests but the only downside, the researchers say, is that it is not as accurate.

Kimberly Hamad-Schifferli, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) said: "Typically people perform PCR and ELISA, which are highly accurate, but they need a controlled lab environment. These are not meant to replace PCR and ELISA because we can't match their accuracy. But this is a complementary technique for places with no running water or electricity."

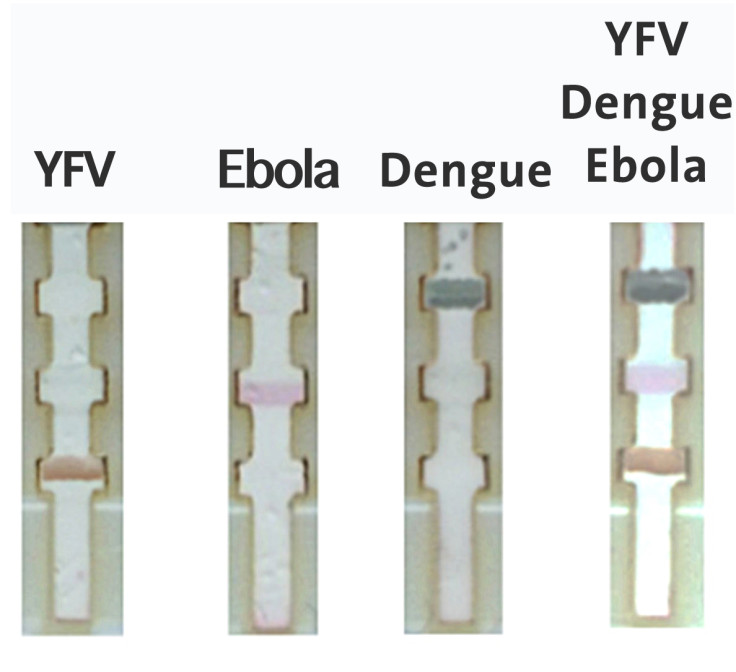

Hamad-Schifferli and her team, which also included members from Harvard Medical School and the US Food and Drug Administration, attached red, green and orange nanoparticles to antibodies that bind proteins from the organisms responsible for Ebola, dengue or yellow fever. These antibodies were then attached to a small piece of paper.

They placed the antibody-tagged nanoparticles to three strips along the paper. "The strip looks so simple, but it's incredibly complicated. Putting it all together in an integrated system was really challenging," Hamad-Schifferli said.

The team of scientists tested the device by using blood samples that contained elements of each disease and placing them on the paper. They use dengue as an example and state that the dengue antibody attached to the green nanoparticles, turning a strip the same colour.

"Using other laboratory tests, we know the typical concentrations of yellow fever or dengue virus in patient blood. We know that the paper-based test is sensitive enough to detect concentrations well below that range," Hamad-Schifferli said. "It's hard to get that information for Ebola, but we can detect down to tens of nanograms per millilitre – that's pretty sensitive and might work with patient samples."

The kits will be handed out freely once they have been mass produced. "We're giving people the components so they can build the devices themselves. We are trying to move this into the field and put it in the hands of the people who need it," Hamad-Schifferli added.

The findings will be presented at the 250th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS).

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.