UK strikes: how Margaret Thatcher and other leaders cut trade union powers over centuries

British trade union membership is currently around 6.5 million, but was more than double that in the late 1970s, when unions worked together to bring the UK to a standstill.

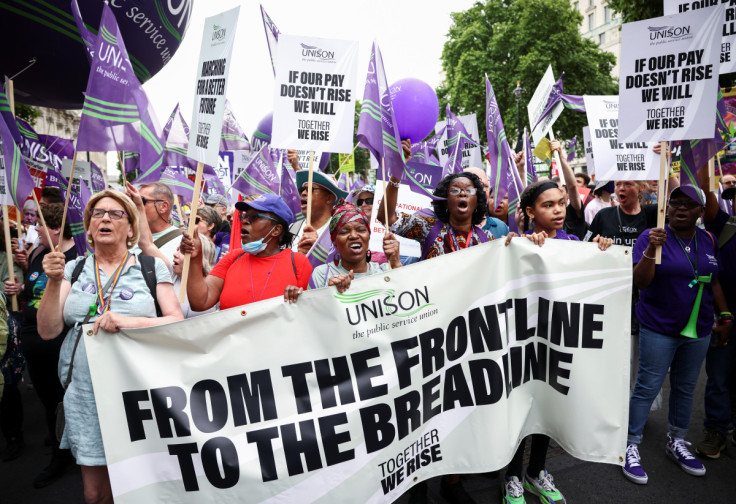

Strikes are often demonised in the UK as outdated and even unethical, but this summer has seen more workers considering and embarking on industrial action. Railway workers from the RMT (Rail Maritime and Transport) union have been among the most visible strikers, but barristers, airline staff and council workers have also taken or considered action, alongside ongoing activity from the likes of university lecturers.

Even as widespread pay discontent builds, British strikers take a great risk by invoking opposition from the government, the media and the public, not to mention the loss of pay they could face during any action. Strikers may be seen as inconveniencing consumers, regardless of whether the workers are taking strike action or have been "locked out". The latter is when employers impose conditions that workers reject, leaving them unable to perform their duties.

Success is not guaranteed. The strength of British trade unions has risen and fallen in line with membership levels and the introduction and repeal of many pieces of legislation since the late 1700s. British trade union membership is currently around 6.5 million, but was more than double that in the late 1970s, when unions worked together to bring the UK to a standstill.

On the other hand, this period also resulted in the election of Margaret Thatcher who brought in a spate of anti-union laws. These laws continue to make strike action difficult to this day, often ensuring action is either illegal or unsuccessful.

The rise and fall of British industrial action

There have been strikes in Britain since at least the late 17th century when skilled workers often briefly took industrial action to get better conditions of work and pay. But strikes were made illegal in the 18th century through various laws covering different trades that were eventually brought under the Combination Acts in 1799 and 1800.

These acts were removed by 1825, but even then legislation continued to control the extent and type of picketing. This made it difficult to effectively strike again until the late 19th century, when the 1871 Trade Union Act allowed unions to become legal bodies.

While this act saw an increase in union formation and industrial action, this activity understandably fell again during the first world war from 1914-1918. After the war, employers attempted to reduce wages, causing workers to start striking again.

By the time of the 1926 General Strike, 2.8 million workers were on strike, costing the nation 162 million days in lost work, compared to just under 8 million days in 1925 and a little over 1 million days in 1927.

An increase in strike activity after the second world war eventually led to the most successful period of strikes in British history. Faced with a high level of inflation in the late 1970s, trade unions began to demand substantial wage rises to help members cope with the cost of living. This led to the 1978-1979 winter of discontent.

Strikes in multiple industries during this period often produced substantial pay rises. But the strikers were pilloried by the press and negative public sentiment led to the election of Margaret Thatcher in May 1979.

Her Conservative government introduced major restrictions on trade union power that were extremely effective. The number of working days lost to strikes fell from nearly 29.5 million in 1979 to a little over 4.3 million in 1981.

Strength in numbers

The impact of strikes – and perhaps even public support for them – is highly dependent on trade union membership. This has also seen peaks and troughs throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and into this one (see graph below).

After a peak of about 13.5 million in 1979, new controls imposed after the Winter of Discontent forced union membership numbers downwards to a little over 6 million people by the end of the 20th century. It has since remained stable until a slight increase to about 6.5 million in 2021.

UK trade union membership levels

UK trade union membership levels peaked in the late 1970s and are currently about 6.5 million people. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy

The five employment acts and one trade union act introduced by the Thatcher and John Major Conservative governments of 1979 to 1997 severely reduced the powers of trade unionism in Britain.

They restricted the right to picket and prevented unions bringing their members out in support of other unions. They also required ballots for strike action (later enhanced to require 50% of members to vote), the failure of which would invoke a fine and seizure of assets.

While the miners' strikes of 1984-1985 tested some of this legislation, subsequent Tory laws survived. Neither of the Labour governments that came after withdrew any of the restrictions on union activity resulting from this legislation.

Alongside the rapid decline in trade union membership since 1979, unions have also been less likely to call industrial action. Apart from the 26 million working days lost during the miners' strike of 1984-1985, the number of days lost annually has only breached 2 million once, in 1989.

More recently, however, the return of high inflation, the failure to match public sector wages to cost of living increases and the impact of the COVID pandemic has seen a rise in strike activity. The summer's rail strikes and the threat of more to come this autumn and winter have led to some discussion of the potential for another winter of discontent.

But strike activity now depends on ballots and trade unions organise only about a fifth of the UK labour force – 6.5 million people out of a total workforce of around 33 million. Undoubtedly, there will be some successes.

Earlier this year, for example, Unite the union said it secured 20% pay rises for around 300 HGV divers and 21% for a similar number of Gatwick airport workers. A more recent 13% deal for British Airways employees "goes some way" to restoring pre-pandemic pay levels, Unite says.

Indeed, it's more likely that the majority of workers will settle for much less from the sluggish British economy. But this could store up frustration among public sector workers for further action in the future, particularly as the UK faces ongoing price inflation.

Keith Laybourn does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.