Why Do Gamers Obsess Over Review Scores?

Venomous responses to 'wrong' reviews are commonplace in the world of video games, and it all stems from those little numbers.

On 16 September 2013, Grand Theft Auto V's embargo lifted and reviews flooded the web.

Gamers around the world were excited to see whether the long-awaited sequel lived up the hype, and on the basis of those first reviews it absolutely did. High scores rained down on Rockstar's crime epic, but one review in particular caught the attention of the gaming world.

GameSpot's review inspired such fury in some quarters of the online community that a petition was set up to have its writer - Carolyn Petit - fired. Her crime? Criticising GTA 5's portrayal of women, and giving the game a 9/10.

Anonymous web commenters flooded in to give their opinion of the opinion of Petit. "Playing it right now, it's a 10. This reviewer's prejudice has clouded her opinion of what otherwise is a masterpiece," said one. "'Politically muddled and profoundly misogynistic', why Gamespot keeps judging games using this kind of s**t? It's a game, don't give me a political lecture or philosophy class," accused another.

These were just two of the less-loathsome examples. Many more were too vile and incoherent to repeat - viscous, misogynistic attacks against Petit from hundreds of enraged gamers.

'We're remarkably lazy creatures'

It is not the first time a critique has inspired such anger, and it won't be the last. Why though, do some react so furiously to opinions that differ from their own? And why do we as a culture obsess so much about those little numbers at the end of reviews?

"They're easy to understand, take less effort, and fit easily into existing conceptions of how to measure quality," says videogame psychologist Jamie Madigan. "Reading all that text and dealing with its ambiguities is hard. We're remarkably lazy creatures. A lot of people also look to scores to validate and repeat their own opinions, or to provide evidence for existing opinions."

Opinions are wonderful things. Everyone has them, they inspire great debate, but they also bring out the worst in people. An increasingly online world has told us that our opinions matter - but some have misinterpreted that as meaning their opinions are of the utmost importance, leading to attacks on those that don't conform to their "superior" viewpoint.

Disagreement, obviously, is at the core of gamer rage. Those schoolyard scraps over which console, which game was better – Microsoft Vs Sony, Mario Vs Sonic – are now prevalent on hundreds of forums and in countless comment sections, concerning every detail of our gaming world. Only online it's not just schoolboys who are slinging jibes at one another.

A difference of opinion is one thing, but why do some gamers take it so much further, making personal attacks and throwing racist, homophobic, sexist remarks around to try and "win" an unwinnable argument?

"People use products, brands, and purchases to create and communicate their identity - at least in part," continues Jamie, who goes on to cite multiple consumer psychology studies about what has been called "self-identity theory".

"If we identify as part of a group, we will identify with the products that group uses. So when someone attacks a brand or a franchise that is close to our identity, they are in a way attacking us.

"We could take that new information – such as a review - into account and either change how much the product means to our identity or downgrade our perception of it. Or, we could attack the credibility of the review and the person making it, which allows us to maintain our identity.

"Guess which option most people opt for if they can?"

Deputy editor of Eurogamer.net and former reviews editor Oli Welsh says gamers hold scores so dear due to changes in how games are critiqued.

Speaking of the roots of game criticism in the 1980s he says: "Back then, reviews were - at least in part - a rather dry benchmarking process that would look first at how well a piece of game software worked, and what the quality of craftsmanship was in superficial elements like graphics and sound."

"There was an air of scientific objectivity to it, like a consumer product review. In the years since, as the technical quality of games has improved to a certain reliable level, the critical style has changed. Most critics now review games as works of art and entertainment - but the scoring, in readers' minds, hasn't really caught up with that change."

Cara Ellison, who writes for The Guardian, PC Gamer and Rock Paper Shotgun agrees, adding that the old style of objective reviews means that "games are thought of as being more technology fetishism than art."

"It also comes from a time when the majority of games players and makers were white men with computer science degrees or at least a cursory intellectual interest in technology," says Ellison. "So any opinion that came down from high on a game was deemed an 'objective' judgement, from expert to expert, man to man."

'Games are thought of as being more technology fetishism than art'

Freelance writer Chris Schilling – who has reviewed games for The Telegraph, Official Nintendo Magazine and Eurogamer among others - remembers the reaction to his first-ever published review eight years ago.

"It was a response to nothing more than the score: a single number, taken completely out of context," he says. "Someone posted the 5/10 rating on a forum, and the very first response was 'Either that reviewer didn't play the game, doesn't understand the genre, or is on crack. Or all three.'

"I laughed. It was actually quite helpful in terms of getting used to the fact that my opinions were now going to occasionally provoke this kind of reaction."

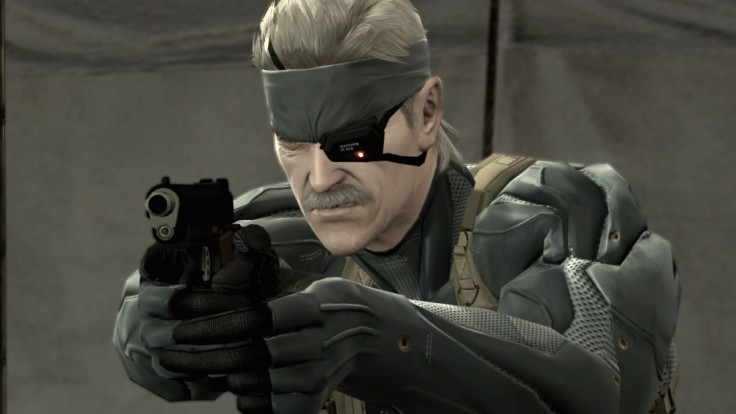

Similarly Welsh remembers when he reviewed Konami's Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots.

"The backlash was one of the worst we've ever experienced," he says. "2300 comments and a deluge of messages for me containing illiterate death threats or other bits of creative nastiness. Reading harsh or insulting comments on your work is often dispiriting, but actually in this case the ludicrous scale and intensity of it made it kind of fun, and some of the most hideous insults - which sadly I can't repeat - were also the funniest!"

Chris goes on to say that videogames themselves also play a part in "knee-jerk reactions" to reviews.

"Games put us at the centre of their universe, and many of them ask us to make binary choices. Recently we've seen more games that introduce shades of grey, but for the most part it's black or white, kill or be killed, and the people who play the most - and who are consequently among the most active on forums and comment threads and such - get conditioned into making snap decisions.

"Twitter's the same. It encourages instant, unfiltered opinion - and I think that's why this kind of culture is worse than ever. It seems there's not enough time or room for nuance these days."

'Toxic disinhibition'

How, though, can this epidemic of personal attacks and naysaying be remedied? I asked Berni Good, psychologist and founder of Cyberpsychologist Ltd.

"It's very hard to police virtual communities and very hard to keep a lid on strong emotions such as jealousy and envy," she says. "It's also difficult for individuals to avoid the disinhibiton effect in online environments."

Good explains that the disinhibiton effect occurs when "an individual will loosen the social constraints and restrictions that they would normally comply with in face to face settings" while in an online environment, making them more likely to make attacks.

Disagreeing that it may be a generational phenomenon, Good says: "Gamers have always defended fiercely the games they play and slated other games, I guess it's more about the ease of accessibility to computer-mediated communication that has really allowed for uncensored communication for the reasons of anonymity and invisibility, around game reviews and or a lack of eye-contact with reviewers that contributes to this toxic online disinhibition."

Jamie Madigan doesn't think there is an easy way of stamping out the problem. "People seem to want easy ways to digest and communicate information, and trends don't seem to be going in the other direction", he says. "I think the best that companies can do is provide both scores and well written and well-reasoned text to go with them."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.