World Cup 2014: Paraplegics Will Walk Independently in Mind-Controlled Robotic Suits

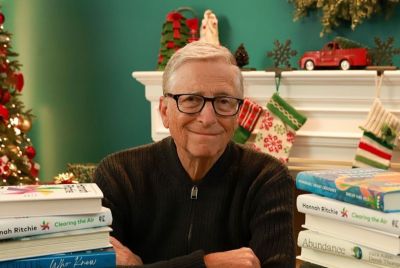

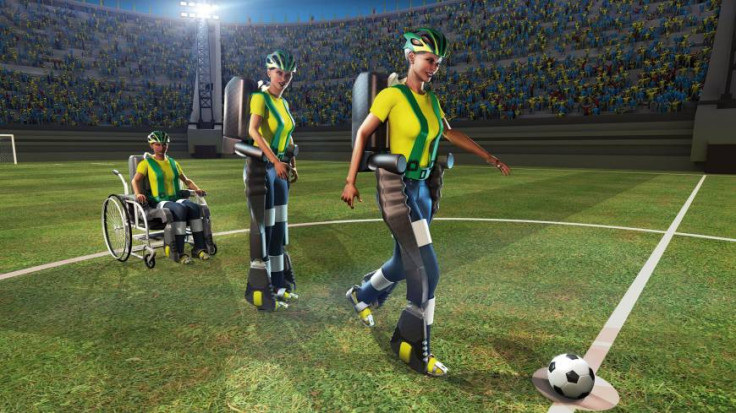

For the first time ever, on 12 June three young adult paraplegics wearing mind-controlled exoskeleton suits will stand up, walk and kick a football at the opening ceremony of the 2014 World Cup in São Paulo, Brazil.

The robotic exoskeleton suits are the results of 12 years of research and work by the Walk Again Project – an international group of engineers and scientists headed by Dr Miguel Nicolelis, a neuroengineer at Duke University in North Carolina.

In 1999 Nicolelis, together with co-author John Chapin and other colleagues, published the first study demonstrating that the brain of a rat could be used to control a robotic device in real-time.

However it wasn't until 2002, after tests with monkeys proved successful, that Nicolelis realised that there was a possibility that humans would be able to control robotic devices with their brains.

But in order to bring his dream to life, he needed help from scientists experienced in working with humanoid robotics, so he brought in Dr Gordon Cheng at the end of 2006, a professor who founded the Institute for Cognitive Systems at the Technical University in Munich.

"The main goal of the project is to demonstrate that a brain-machine interface can be the centre of rehabilitation," Nicolelis tells IBTimes UK from São Paulo, where he and a team of scientists are racing against the clock to prepare three paraplegics in their 20s and 30s who have been specially trained to operate the exoskeleton suits.

"Walking is the only beginning. That is the most immediate objective, but the technology could also restore upper limb movements and functions to allow patients to be able to speak again, by establishing a direct link between the brain and machines."

How the suit works

While Nicolelis pioneered the machine interface that enables the mind to control the suit, Cheng designed the robotics, and the exoskeleton was built by French researchers in Paris.

The exoskeleton suit is a full-body suit that houses the person and enables them to walk again. A large part of the suit is covered in artificial skin containing a variety of sensors that enable the wearer of the suit to feel touch, pressure, temperature and vibrations, the same way people without disabilities do.

The sensors are connected by wires to a computer running on Raspberry Pi that sits on the suit, controlling the signals in the background while the person's mind, connected to the suit by a cap worn on the head, controls the movements.

"Miguel and I proved the concept in 2008. We ran an experiment that allowed one of my humanoid robots to be controlled by one of his brains in a living monkey. [The monkey] in North Carolina could control my humanoid robot in Kyoto, Japan. That's when we knew," he tells IBTimes UK.

Nicolelis and his team decoded the walking signal sent from the monkey's brain and sent it to Cheng, where he and his scientists used the signal to control a humanoid robot on a treadmill.

Yet learning to control a robotic device with your mind is not as simple as learning to walk. Nicolelis and his team have had to train their patients through a painstaking process in order to teach them how to use the suit.

It's all in the mind

To do this, nine patients, both men and women, began training in December 2013. They were put in a virtual reality environment and taught to control an avatar on a virtual football pitch.

Over time, as the patients learned to control their avatars with their minds, their brains began to receive feedback and the patients began to feel the sensation of the avatar's foot touching the virtual ground.

"Since we gave constant feedback to the brain, the patients started having the illusion that their legs could move again. What we want is not only for them to be able to move the exoskeleton, but we want the exoskeleton to become an extension of themselves," explains Nicolelis.

After the patients completed the first stage, they were then put into a suspended simulator, whereby a robot moved their legs, which improved their sensation that they were controlling the exoskeleton suit.

Nicholelis says that more research papers about the next generation technology will be released in the next two months, and he thinks that the Walk Again Project's research will be a surprise to many.

"Once the World Cup is over, we're going to sleep for three months. Of course we hope that one day [the suit] will help to make the wheelchair obsolete, but we also think that this is a key tool in better understanding how the brain constructs a sense of self," he says.

Cheng believes that although the technology behind the suit is currently expensive, soon it will become affordable for patients.

"We're pushing the boundary by reducing the suit's costs. I think it will take less than 20 years, hopefully we could do it in 10. Our agenda is a societal agenda, we want to help people."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.