BlackBerry Buyout: Ten Years of Boom and Bust

As BlackBerry looks set to be bought out by Fairfax Financial Holdings for $4.7bn, Alistair Charlton looks back over ten years of boom and bust for the Canadian phone maker.

In the six years since the iPhone was announced in January, 2007, the share price of BlackBerry - formerly known as Research in Motion - has dropped from $230 to less than $9; and despite minor recoveries in early 2008 and 2009, the figure has fallen almost continuously in that time. Below is a brief company history, starting with its first smartphone in 2003.

2003 - The smartphone is born

Although founded in 1984, it was from 2003 that Research in Motion (now known as BlackBerry, which I'll be sticking with) had the smartphone world at its feet. The first mobile phone manufacturer to deliver real-time 'push' email to its users, the Toronto, Canada-based company saw the future of the smartphone before any of its rivals.

BlackBerrys - named due to the fruit seed-like shape of their iconic keyboards - quickly became the must-have accessory for any professional who wanted to be taken seriously. Nothing said you're an important, hard-working, high-earner quite like firing off emails on the train home at 11pm on a Monday night, signed off with 'Sent from my BlackBerry'.

With products boasting a physical Qwerty keyboard unmatched by its rivals and phone encryption secure enough to be used by central government the world over, company co-CEOs Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie had grown their business into an enviable position, and its move to the consumer market with multicoloured handsets and BBM messaging service seemed the logical next step.

2007 - iPhone arrives, but poses no immediate threat

On 9 January, 2007, Steve Jobs' unveiling of the iPhone caused RIM's share price to fall 8%. The phone featured an email client of its own and a virtual keyboard which Apple claimed to be far superior to that of BlackBerries or any other mobile phone.

The iPhone arrived six months later with a high price and an exclusivity deal with AT&T in the US and O2 when it arrived in the UK in November. Apple's product was interesting and different, but even Jobs himself admitted the company faced an uphill battle to steal any meaningful market share from the dominant Nokia, Motorola and BlackBerry.

RIM's co-CEOs dismissed the iPhone, claiming its touchscreen keyboard was no match for physical buttons. "As nice as the Apple iPhone is, it poses a real challenge to its users," Balsillie said. "Try typing a web key on a touchscreen on an Apple iPhone, that's a real challenge."

2008 - A touchscreen phone of its own

A year later, BlackBerry launched the Storm, a full touchscreen phone with a display that clicked when tapped. Known as SurePress, the system was slated for being awkward to use and slower than the iPhone.

While the iPhone remained locked to a select few carriers with a high price, BlackBerry continued to hold position, adding new and improved handsets which were still unique in their ability to provide safe and secure encryption for business users; the security provided by the iPhone and new Android phones wasn't yet suitable in the enterprise market.

2010 - BlackBerry reaches peak US market share, but still growing internationally

BlackBerry reached its peak in the US in autumn 2010 with approximately 21 million users, but as US interest waned from then on, sales in the emerging markets of Europe and the Middle East kept global interest high, and worldwide subscribers continued to grow, eventually maxing out at 79 million in December 2012.

But as deserting US users showed, the writing was already on the wall. At this point the company was heading for gradual decline, as workers who had previously been addicted to their BlackBerry soon realised the iPhone and others offered much more - and as the security of iOS and Android improved, the BYOD (bring your own device) phenomenon took hold. Employers relaxed their rules about what devices workers could use, and some even began to issue alternative phones to staff.

BlackBerry's once monopolistic grip on the enterprise smartphone market was weakening - but forecasts of gradual decline were soon turned to "death spirals" as a series of increasingly calamitous events in 2011, '12 and '13 tore the company apart.

2011 - Annus horribilis

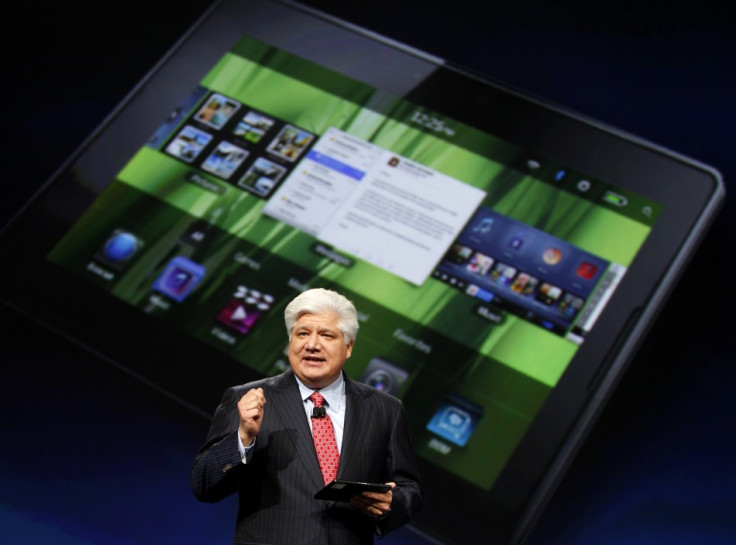

In 2010 Apple announced the iPad, and although Microsoft and others had tried to produce tablets before, Apple appeared to have cracked it. Based on the iPhone's operating system and with a £429 price tag, the iPad went on to be a success, prompting rivals to invest heavily in a tablet market now hungry for cheaper alternatives.

The same year, rumours began circulating that BlackBerry was working on its own tablet, and by the autumn the company named the upcoming device PlayBook - a tablet it claimed to be faster than the iPad and under $500 (£312). "Amateur hour is over", it's adverts read.

In April 2011 the PlayBook went on sale in the US and Canada, with Europe following later. The tablet had competitive hardware and a 7in screen that was smaller and more portable than the 9.7in iPad - but a lack of native email, calendar and contacts applications meant users had to pair the PlayBook over Bluetooth to their BlackBerry phone in order to access these key services. A native email app was promised within 60 days, but it would not arrive for 10 months.

In the meantime, BlackBerry's own shipment figures fell from 500,000 in the first quarter on sale to 200,000 then 150,000; actual sales figures were never revealed.

Several price cuts followed but sales continue to fall and in December 2011 the company took a $459m write-down on unsold PlayBook stock. Later that month the company lost an estimated 5,000 PlayBooks, when a truck they were in was stolen.

Six senior executives left the company between March and September, including chief operating officer Don Morrison, leaving Thorsten Heins to take on more responsibilities as COO, before eventually becoming CEO a year later.

Blackout

On 10 October, 2011, a hardware failure meant millions of BlackBerry users the world over were unable to access their email, internet or social networks.

For the first two days BlackBerry refused to comment, leaving networks to keep angry users informed about a problem they had no control over. By day three, CEO Lazaridis issued a video statement, apologising for the mass outage, which cost the company over $50m in revenue.

BlackBerry's services came back online on 13 October, but the company wasn't out of the woods yet. The previously-announced BlackBerry 10 operating system (whose name had to be changed from BBX, following a threat of legal action) was delayed by a year to "late 2012" - the company citing the need to wait for new, more powerful processors.

As 2011 drew to a close, BlackBerry had lost 75% of its value, its share price hitting a seven-year low and at one point dropping below book value - the total value of its assets, such as buildings, corporate jets and unsold stock. Essentially, BlackBerry was worth more as scrap than as a functioning company.

One last sting in the tail of 2011 came in December, when two BlackBerry executives disrupted an Air Canada flight to China, which had to be diverted to Vancouver Airport. Each was fined CA$35,878 (£22,000) and pleaded guilty to mischief, earning them suspended sentences and probation for one year.

2012 - A waiting game begins as BB10 delays drag on

In January 2012 CEOs Mike Lazaridis and Jim Balsillie stepped down, promoting Thorsten Heins to the top job.

By now, everyone knew that BlackBerry 10 was on its way - despite the setbacks - and so sales of older Blackberry 7 devices, at least in the consumer sector it so desperately wanted a slice of, began to dry up.

With BlackBerry 10 and new hardware in development, Heins remained confident in his company. "We're not just a service company," he said shortly after taking the role of CEO. "We run a network, we run services and we run devices and we can create formidable integrated solutions. This is a very unique position in the wireless landscape."

Controlling both the hardware and software is a position enjoyed to maximum effect by Apple and the iPhone, but any hopes of BlackBerry mirroring this would soon be dashed when the arrival of BB10 in early 2013 failed to capture consumers' imagination.

2013 - End game

After a year stuck in limbo between the soon-to-be-replaced BlackBerry 7 and supposedly game changing BlackBerry 10, the new software and phones arrived via a global press event taking place in six cities simultaneously.

Research in Motion changed its name to BlackBerry, Alicia Keys was hired as 'creative director' and the company purchased prime sponsorship space on the Mercedes Formula One team's cars and team clothing.

Initially, BB10 looked good, with a hugely impressive touch screen keyboard - which I still claim to be the best I've ever used - a powerfull unified inboxes, solid hardware and the company's famous encryption and enterprise software.

The Z10 and, later, Q10 smartphones reviewed well enough, but were simply too little, too late. Three years earlier, they would have been worthy iPhone rivals, but in 2013 - and once the 'BlackBerry turnaround' headlines had subsided - their prices fell, as did the sales figures and, once again, the company share price.

First-quarter financial results announced in June saw a $518m loss, causing stock to plunge almost 30% in a single afternoon, never to recover. On the same day, it was announced that an update bringing BB10 to the PlayBook had been cancelled.

The company announced in August that it would consider selling all of part of itself; this was followed by the reporting of a $1bn loss and 4,500 redundancies (40% of its total workforce) in September.

Now, as BlackBerry enters what could be its final weeks as a public company, it seems likely that Fairfax Financial Holdings will buy it for $4.7bn (£3bn).

When Steve Jobs announced the iPhone in 2007 he was entering a market led by Motorola, Nokia and BlackBerry. Now, Google owns Motorola, Microsoft is in the process of buying Nokia's phone business, and BlackBerry will struggle to see 2014 under its own steam.

The iPhone can't be blamed (praised?) for claiming all three scalps, but it, along with Google and Samsung, has shown how no technology company, no matter how heavily used and relied upon by institutions and consumers the world over, can be too big to fail.

All eyes will now be on HTC, which is soon expected to post its first quarterly loss in 11 years of being a public company.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.