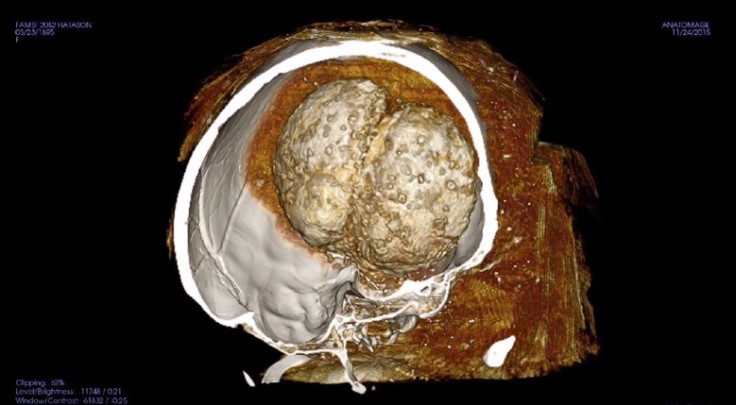

Brain of 3,200-year-old Egyptian mummy Hatason revealed through CT scans

CT scans of an ancient Egyptian mummy have revealed a never-before-seen technique used to preserve the brain. Scientists at Stanford University were analysing the remains of a woman who lived in the city of Asyut 3,200 years ago known as 'Hatason'.

The woman (researchers believe she is female but are not entirely sure) lived in what was a rich culture at the crossroads of several trade routes. Asyut was at the north end of the Darb el-Arba'īn, the Forty Days' Road, the 100-mile road through the desert in Darfur. It would have been well defended by soldiers due to the gold, ivory and spices passing through.

Her mummified body was shipped to San Francisco sometime in the 19<sup>th century and was put on display in Golden Gate Park. Eventually she was donated to the de Young Museum. Now, scientists hope to learn more about who she was with advanced imaging technology.

The name Hatason is believed to have come from a corruption of the name of the famous Queen Hatshepsut. Private collectors liked the idea of buying royal mummies so sellers would associate names to make them sound regal. Another problem is that the coffin she was found in: the sarcophagus in which she was found showed a woman in everyday clothes, but coffins were often reused and mummies swapped around.

Researchers placed the mummy in the scanner to create a complex set of 3D patterns. Images returned showed her brain was still inside her skull resting on top of a pile of dark material believed to be sediment. "It's some form of material added into the brain case while the brain was left inside," said Jonathan Elias, director of the Akhmim Mummy Studies Consortium. "We have not seen that particular pattern before."

The bones of her nose were intact, suggesting no one had tried to remove her brains (the most common method was through the nasal passage). Had she been mummified 1,000 years later, the brain would have been removed – Hatason lived in an experimental period of mummification.

All of the mummy's organs had gone and her bones had moved around quite extensively over the years. Her pelvis had collapsed meaning her sex could not be determined, but her skull suggests it was that of a young woman. The team is currently processing the images and expects to reveal more details about the mummy soon. "There are not that many mummies from this era that have been researched," Elias said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.