Chinese scientists edit genomes of human embryos as rumours emerge of 'secret' experiments

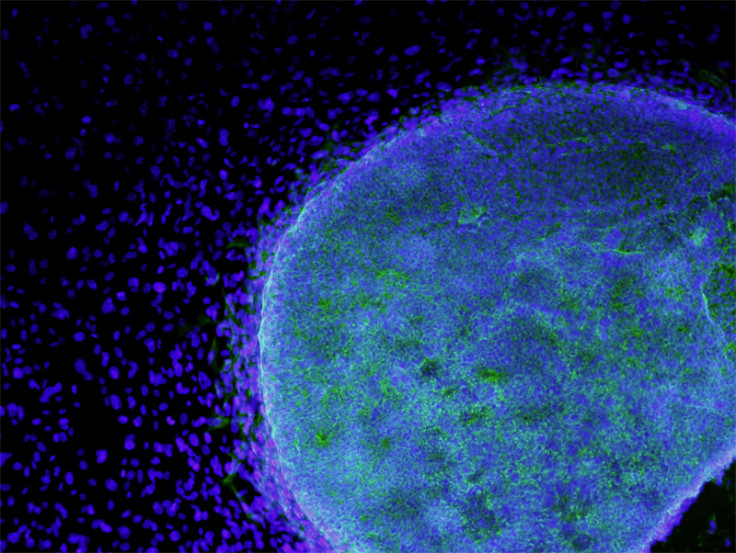

For the first time ever, scientists have edited the genomes of human embryos – an announcement that has raised widespread debate about the ethics of experiments like this.

The researchers, from at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, successfully injected embryos with an enzyme that can be programmed to target the gene responsible for a potentially fatal blood disorder.

They attempted to use a gene-editing technique called CRISPR and the results revealed some major obstacles.

Of the 86 embryos used in the experiment on the technique, which has been successfully performed on cows, pigs and monkeys, only 28 were successful, with only a fraction of these containing the replacement genetic material.

Research leader Junjiu Huang told Nature magazine: "If you want to do it in normal embryos, you need to be close to 100%. That's why we stopped. We still think it's too immature." Publishing their findings in the journal Protein and Cell, the authors also said that the gene editing had caused unintended mutations in other genes.

"To date, a serious knowledge gap remains in our understanding of DNA repair mechanisms in human early embryos, and in the efficiency and potential off-target effects of using technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 in human pre-implantation embryos," they wrote, saying that while the technique could be used to effectively cleave the gene, efficiency was low and the edited embryos were "mosaic".

Researchers obtained the embryos from local fertility clinics. They got past ethical concerns by using non-viable embryoes, which cannot result in a live birth.

However, some said the findings should serve as a warning for future experiments.

George Daley, a stem-cell biologist at Harvard Medical School, told the magazine: "I believe this is the first report of CRISPR/Cas9 applied to human pre-implantation embryos and as such the study is a landmark, as well as a cautionary tale. Their study should be a stern warning to any practitioner who thinks the technology is ready for testing to eradicate disease genes."

The study comes amid reports of further secret testing on human embryos in China. A source working in the field told Nature there are other groups pursuing gene editing in human embryos.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.