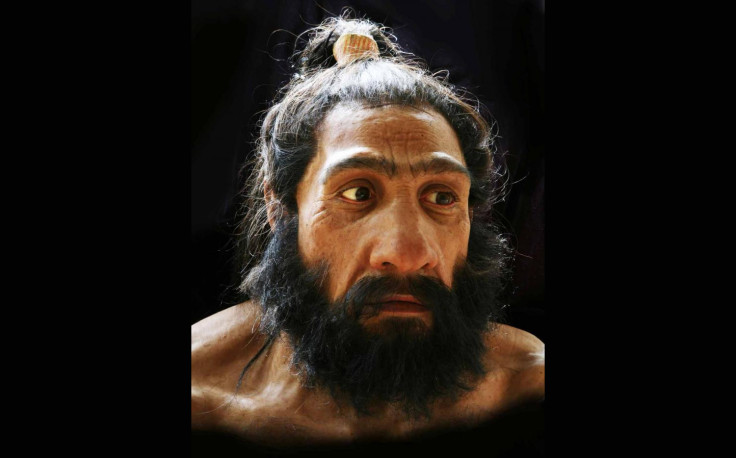

Crohn's and sickle cell anaemia evolved to protect Neanderthals from deadly diseases

Sufferers of psoriasis, Crohn's disease or sickle cell anaemia, which are hereditary conditions, might be interested to know these ancient diseases evolved in order to protect our ancestors from even worse medical conditions.

A group of international scientists have been studying how the human genome has evolved over thousands of years by comparing it to species closely related to us, such as chimpanzees, as well as Neanderthals and Denisovans (archaic humans that modern humans evolved from).

Their study, entitled "The Evolution and Functional Impact of Human Deletion Variants Shared with Archaic Hominin Genomes" is published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

The researchers discovered chunks of DNA present in chimpanzees have been erased over time through evolutionary processes (known as "deletions") and are now present in only some human genomes.

Why were segments of DNA deleted?

The human genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes. In order for an organism to grow and function, its cells must constantly divide and replicate, copying all of the genes from one DNA molecule to another.

The scientists say the DNA deletions occurred in a common ancestor of humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans about a million or so years ago, in order to make humans in certain parts of the world deliberately susceptible to various health conditions.

"The best example of this is sickle cell anaemia," said senior scientist Dr Omer Gokcumen, an assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Buffalo (UB) in New York, who co-authored the study.

Sickle cell anaemia is a serious blood disorder that causes red blood cells to take on a curved, crescent-like shape, which leads to anaemia (a problem) but also protects against malaria, a deadly infectious disease, by keeping parasites out of cells (an advantage).

This blood disorder mainly affects people of African, Caribbean, Middle Eastern, Eastern Mediterranean and Asian origin, which is where malaria is an ever-present danger.

As such, the human genome of people from these areas contains a copy of the gene that causes sickle cell anaemia.

Genetic variations important to understanding health

While the scientists are not sure exactly what Crohn's disease (a long-term stomach condition) and psoriasis (a chronic skin condition) protected ancient humans against, they do know that it was probably related to invading pathogens.

"Crohn's disease and psoriasis are damaging, but our findings suggest that there may be something else – some unknown factor now or in the past – that counteracts the danger when you carry genetic features that may increase susceptibility for these conditions," Gokcumen said.

"Both diseases are autoimmune disorders, and one can imagine that in a pathogen-rich environment, a highly active immune system may actually be a good thing even if it increases the chances of an auto-immune response."

In fact, more emphasis should be made into researching how genes have evolved in different parts of the world.

"[Ancient genetic variations are] underappreciated," said Yen-Lung Lin, a PhD candidate in UB's Department of Biological Sciences, who is lead author in the study.

"We're thinking forces that maintain variation might be more relevant to human health and biology than previously believed."

The study was a collaboration between University of Buffalo, the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology in Greece and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Germany.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.