Deadly Irukandji Jellyfish 'to Become a Global Threat' as Oceans Warm

A deadly breed of jellyfish looks set to become a global threat as climate change warms the ocean.

Researchers have said the Irukandji jellyfish look likely to spread into the waters of south east Queensland and will reach Sydney in the next 70 years - a trend predicted to take place across the globe.

Irukandji jellyfish are extremely venomous and currently inhabit northern Australia, but have also been found in Japan, Florida and the British Isles.

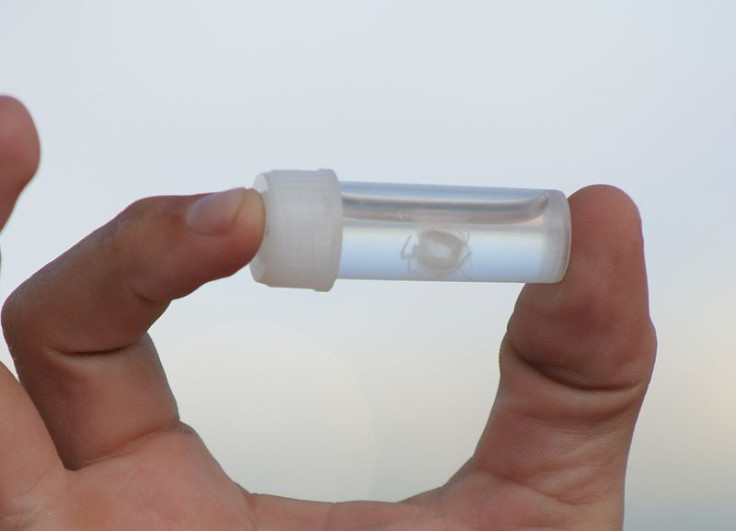

They only measure around one centimetre in length but their sting can cause severe muscle cramps, extreme back and kidney pain, burning sensation to the skin, nausea, sweating, vomiting and increased blood pressure. Since 2002, two people have died from Irukandji jellyfish stings.

Researchers at Griffith University's Australian Rivers Institute conducted a number of climate change simulation experiments to establish whether these jellyfish will establish breeding populations in south east Queensland.

They found that the higher sea temperature caused by climate change would provide Irukandji jellyfish with the opportunity to expand their range.

Historically, the species has been limited to the waters off Gladstone to the north, but an adult specimen was found for the first time in Hervey Bay in 2007.

The study is the first to assess if the jellyfish pose a significant threat to tourism in the area.

Lead author Shannon Klein said: "Increasing ocean temperatures and strengthening boundary currents have caused the poleward migration of many marine species."

"These effects of climate change are particularly apparent on the eastern coast of Australia. Over the past 60 years the East Australian Current has strengthened and now delivers warmer tropical waters further south by as much as 350km."

Global threat

The authors say if current rates of warming continue the Irukandji would be able to survive in waters of Sydney in New South Wales by 2080.

They believe the jellyfish would have the biggest socio-economic impacts of any other species migrating as a result of climate change.

Shannon said that there may be some reprieve to the Irukandji invasion as the study showed that increasing ocean acidification may inhibit the development of juvenile jellyfish.

However, the researchers warn that this will not eliminate the threat to southerly waters: "This response may reduce the likelihood of Irukandji jellyfish establishing permanent populations in South East Queensland in the long term, however, it is possible that they could migrate farther south in the short term if acidification proceeds slowly and appropriate reproduction habitats are available."

She said that even if juvenile jellyfish remain in northern waters, adults will still be able to expand their range.

"Our results suggest that, if other Irukandji species behave similarly, range expansions could be occurring in other regions around the globe," Shannon said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.