Diabetes: Insulin injections not required with TMTD treatment that shields implanted cells

A new way to treat diabetes has been developed that prevents the need for insulin injections or immunosuppressants, say researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The scientists found a way to create a protective shield around new, fully functional pancreatic cells so that the immune system does not attack them when implanted.

The study, published in Nature Medicine, uses the material triazole-thiomorpholine dioxide (TMTD), to make encapsulated pancreatic cells developed by stem cells. These can be implanted into Type 1 diabetes patients so that no insulin injections need to be taken again, and the immune system cannot attack the implant.

Why is a the treatment needed?

Replacing faulty cells from the pancreas has been carried out already in hundreds of diabetes patients, but their immune system attacks the implanted cells believing it is an unwanted pathogen. That means they have been forced to take immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of their lives.

This new treatment, which uses a capsule around pancreatic cells that act as a force-field against the immune system, "has the potential to provide diabetics with a new pancreas that is protected from the immune system," said Daniel Anderson, senior author of the research. "[This] would allow them to control their blood sugar without taking drugs. That's the dream."

The investigation

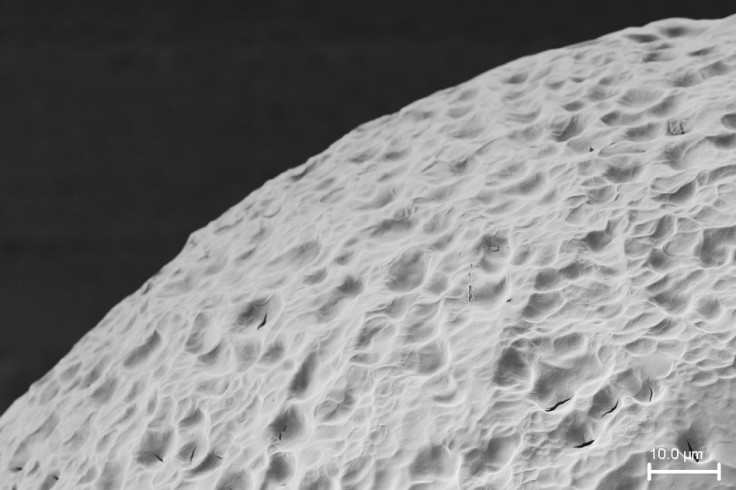

The scientists began their investigation by considering alginate – a material made from brown algae already being used to encapsulate cells. However, research has shown that scar tissue tends to form around these cells, eventually rendering them useless.

They therefore began to experiment with alginate by adding various molecules to its polymer chain. After a process of trial and elimination – and 800 alginate derivatives later – the researchers managed to produce TMTD – the best of all capsuling materials they made.

TMTD was trialled on diabetic mice with a fully working immune system. Pancreatic cells cultured from stem cells were encapsulated in TMTD and implanted into the mice.

The cells produced insulin immediately, and ultimately controlled their blood-sugar levels for the entire 174 days of the study.

"The really exciting part of this was being able to show in an immune-competent mouse, that when encapsulated, these cells do survive for a long period of time – at least six months," said Omid Veiseh, researcher on the study. "The cells can sense glucose and secrete insulin in a controlled manner, alleviating the mice's need for injected insulin."

What is next for the treatment?

The next step of investigation involves testing the pancreatic cell shield in non-human primates. Should that be successful, clinical trials will begin in diabetic humans.

Arturo Vegas, researcher from Boston Children's Hospital said: "Being insulin-independent is the goal. This would be a state-of-the-art way of doing that, better than any other technology could. Cells are able to detect glucose and release insulin far better than any piece of technology we've been able to develop."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.