Earth-like Planet in an Orbital Tug-Of-War with Much Larger Planet Discovered

Astronomers from the University of Washington and the Harvard University have discovered an Earth-like planet locked in an orbital tug-of-war with a Neptune-sized planet. They discovered the two planets while analysing some data retrieved from the Nasa's Kepler telescope.

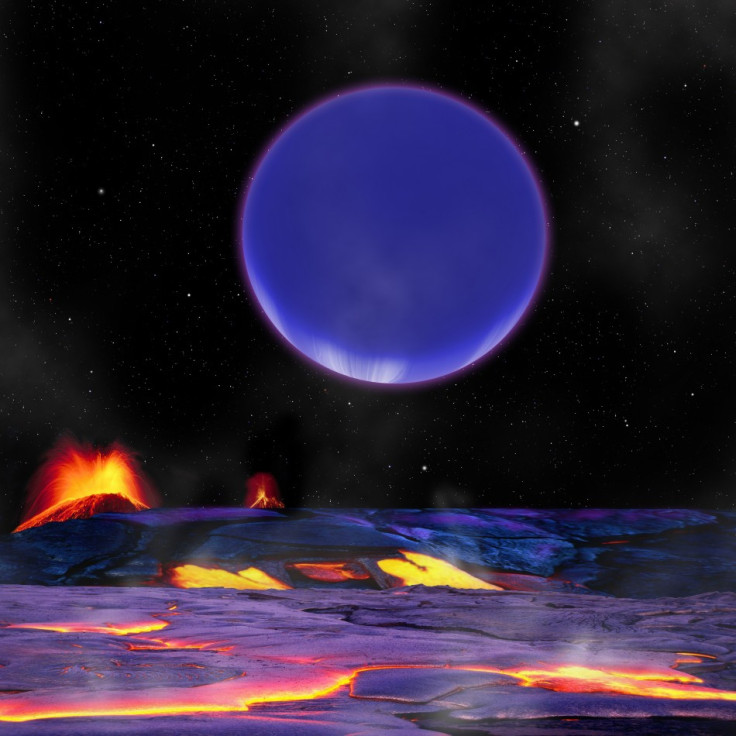

The Earth-like planet, Kepler-36b, is a rocky planet. It is 1.5 times the size of Earth and weighing 4.5 times as much. It orbits about every 14 days at an average distance of less than 11 million miles.

The Neptune- like planet, Kepler-36c, is a gaseous planet. Kepler-36c is 3.7 times the size of Earth and weighing 8 times as much. This "hot Neptune" orbits once each 16 days at a distance of 12 million miles.

During the study, astronomers found that the two planets circling a sub giant star much like the Sun except several billion years older.

The data retrieved from the telescope also revealed that the planets are close to each other and they occupy nearly the same orbital plane.

"These are the closest two planets to one another that have ever been found," said Eric Agol, scientists at the University of Washington, in a statement.

"The bigger planet is pushing the smaller planet around more, so the smaller planet was harder to find," Agol added.

The larger planet- Neptune-like planet- was originally spotted in the data from Nasa's Kepler spacecraft. The spacecraft used a photometer to measure light from distant celestial objects which could detect a planet when it transits, or passes in front of the parent star.

To detect the second planet, astronomers applied an algorithm theory called quasi-periodic pulse detection to examine data from Kepler. They were stunned to find another planet orbiting the same period and they were very close to each other.

"We found this one on a first quick look. We're now combing through the Kepler data to try to locate more," said Joshua Carter, astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in a statement.

The fact that the two planets are so close to each other and exhibit specific orbital patterns allowed the scientists to make fairly precise estimates of each planet's characteristics, based on their gravitational effects on each other and the resulting variations in the orbits.

Astronomers believe the smaller planet is 30 percent iron, less than one percent atmospheric hydrogen and helium and probably no more than 15 percent water. The larger planet, on the other hand, likely has a rocky core surrounded by a substantial amount of atmospheric hydrogen and helium.

However, further studies are required to know more about the planets, according to the astronomers.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.