Flashbulb memory: New experiences boost memory formation, say scientists

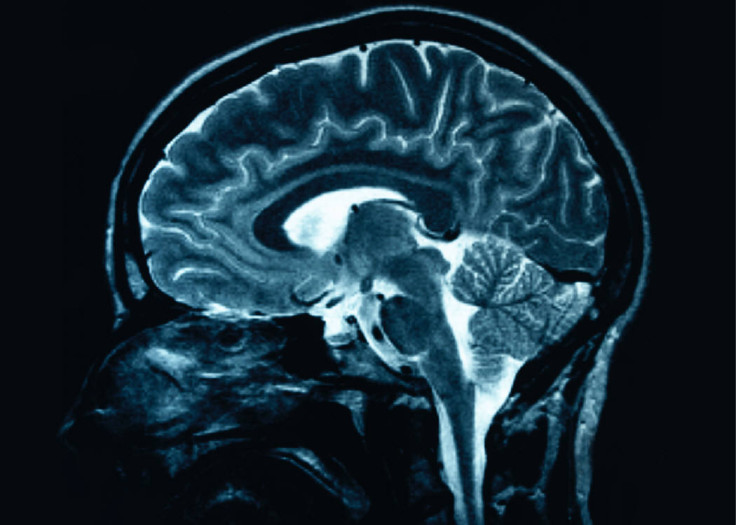

Attention-grabbing experiences activate chemicals in parts of the brain crucial in forming new memories.

Most people remember where they were and what they were doing when a significant event happened – say 9/11, for example. Now, new research led by the University of Edinburgh and published in the journal Nature, is uncovering why this might be the case.

The work has shed light on the biological mechanisms that drive the process – known as flashbulb memory.

The study, which used mice, showed how attention-grabbing experiences activate a specific area of the brain, which then releases memory-boosting chemicals.

The findings help to explain why people retain information better if something distracts their attention either just before or just after a memory is stored in their brain. Experts say the research could have benefits for supporting learning in schools.

The study centred on how everyday memories – such as remembering names – are stored in the brain. The equivalent in mice is remembering the location of a food source.

The team placed mice in an arena to search for hidden food which was placed in a different location each day. They found that animals which had had a new experience – such as exploring an unfamiliar floor surface – within 30 minutes of being trained to remember the location of the food, were better at remembering where to find food the next day.

The team showed that the phenomenon is linked to the release of a chemical called dopamine in a brain region known as the locus coeruleus. They found that this area of the brain is particularly stimulated by new experiences and that brain cells in the locus coeruleus carry dopamine – whose crucial role in forming new memories is well understood – to another area of the brain, called the hippocampus, which controls the formation of memories.

This is the first study to establish a link between the locus coeruleus and the hippocampus.

"Little surprises happen all the time in subtle ways that reflect our personal lives and interests,"said Professor Richard Morris, from the University of Edinburgh. "Somehow, the novelty of surprise creates a halo of better memory for all the otherwise trivial events of one's day that we ordinarily forget. Our research suggests that a skillful teacher may be able to take advantage of these little surprises to help pupils learn and remember."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.