Fungus Attacks Toxic Algae in Major Marine Discovery — Could Help Prevent Human Health Risks

The fungus targets algae associated with respiratory illness, beach closures and ecosystem damage

Scientists have identified a previously unknown marine fungus that attacks toxic algae responsible for harmful blooms, a discovery that could eventually help reduce risks to human health and coastal ecosystems. The organism targets algae linked to respiratory illness, skin irritation and widespread disruption to marine life.

The finding offers new insight into the role of microscopic fungi in ocean environments, an area that has historically received far less attention than bacteria or plankton. Harmful algal blooms are becoming more frequent in many regions, driven by rising sea temperatures and increased nutrient pollution associated with climate change and coastal development.

While researchers stress that the discovery does not provide an immediate solution to algal blooms, they say it could improve understanding of how such outbreaks are naturally regulated. Over time, this knowledge may help inform new ways of monitoring or managing events that threaten public health, tourism and marine ecosystems.

Discovery of a New Marine Fungus

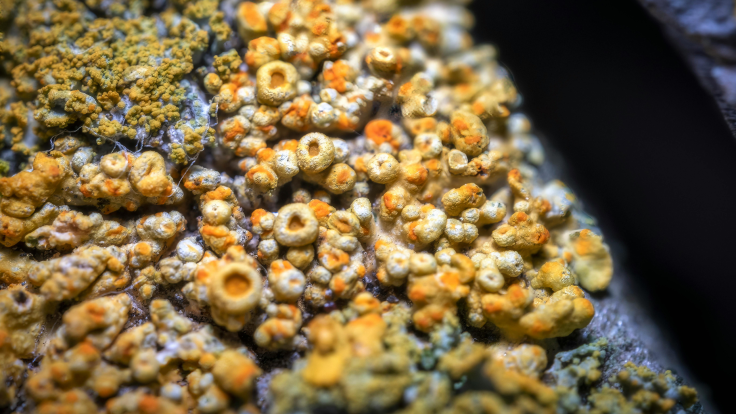

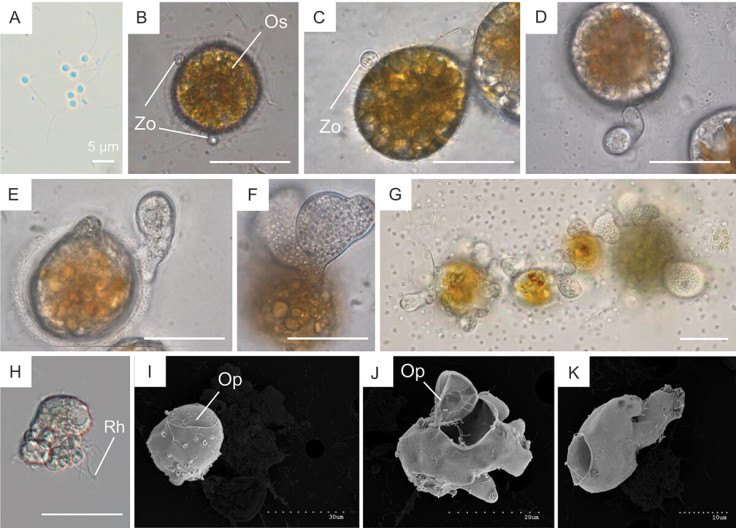

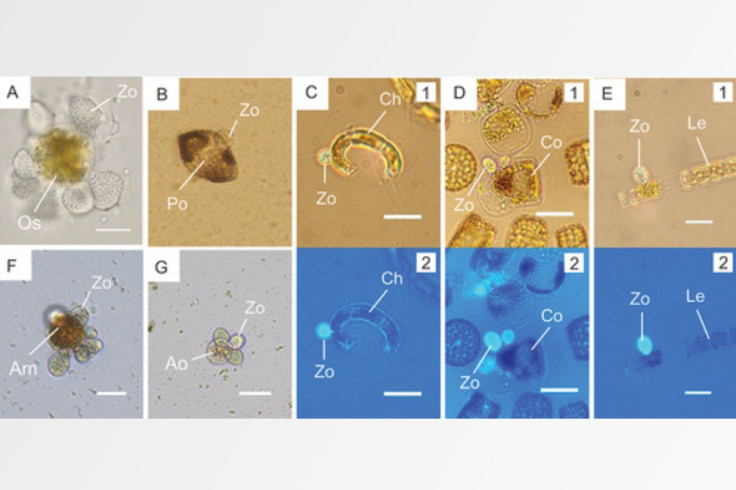

The fungus, named Algophthora mediterranea, was identified by researchers from Yokohama National University in collaboration with European partners. It belongs to a group of microscopic fungi known as chytrids and acts as a parasite of the toxic dinoflagellate Ostreopsis cf. ovata, a species associated with repeated harmful algal bloom events.

The organism was first isolated from Mediterranean seawater in 2021 by scientists at Spain's Institut de Ciències del Mar. Subsequent genetic analysis confirmed that it represents both a new species and a new genus. Researchers also found that it has an unusually broad range of potential hosts, infecting several types of algae and even feeding on pollen grains.

Laboratory experiments showed that the fungus can infect and kill O. cf. ovata cells within a matter of days, effectively halting their growth. Scientists say this suggests marine fungi may play a more significant role in regulating algal populations than previously recognised.

Health and Environmental Impact of Toxic Algae

Harmful algal blooms occur when certain algae multiply rapidly, often in warm, nutrient-rich waters. Some species release toxins that can become airborne or accumulate in seafood, causing respiratory problems, skin irritation and gastrointestinal illness in people exposed.

Ostreopsis cf. ovata has been reported with increasing frequency along Mediterranean coastlines. Blooms have led to beach closures and public health warnings in several countries, particularly during summer months when tourism is at its peak. Similar concerns exist globally as environmental conditions increasingly favour toxic algae.

Beyond risks to human health, algal blooms can damage fisheries, reduce oxygen levels in coastal waters and disrupt entire marine ecosystems, with knock-on effects for biodiversity and local economies.

Implications for Science and Public Health

Professor Maiko Kagami, one of the study's authors, said the next step would be to investigate how parasites such as Algophthora mediterranea behave in complex marine environments. Understanding these interactions could help improve predictive models for bloom formation and decline.

Researchers caution that the discovery should not be viewed as a direct control method. Instead, it highlights the importance of marine fungi in ocean ecosystems and raises new questions about how natural biological checks and balances operate.

As harmful algal blooms continue to pose growing challenges worldwide, scientists say expanding knowledge of these microscopic interactions may prove essential. While practical applications remain distant, the discovery adds to wider efforts to understand how marine ecosystems respond to environmental change and how risks to coastal communities might one day be reduced.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.