How the Eyam plague of 1665 spread among villagers during self-imposed quarantine

This year marks the 350<sup>th anniversary of a major plague outbreak in the village of Eyam, Derbyshire, which claimed 257 lives over a period of fourteen months. Scientists from Imperial College London have now analysed official documents from the episode to get a clearer picture of how the disease was transmitted between villagers.

The Eyam Plague is well known for the heroism of its villagers, who self-imposed a cordon sanitaire during the outbreak to prevent the plague being spread to neighbouring parishes. However, few attempts have been made to model exactly how the disease spread.

The latest epidemiological analysis – published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B - identifies the different routes of disease transmission, showing human-to-human infection was a lot more significant than previously thought.

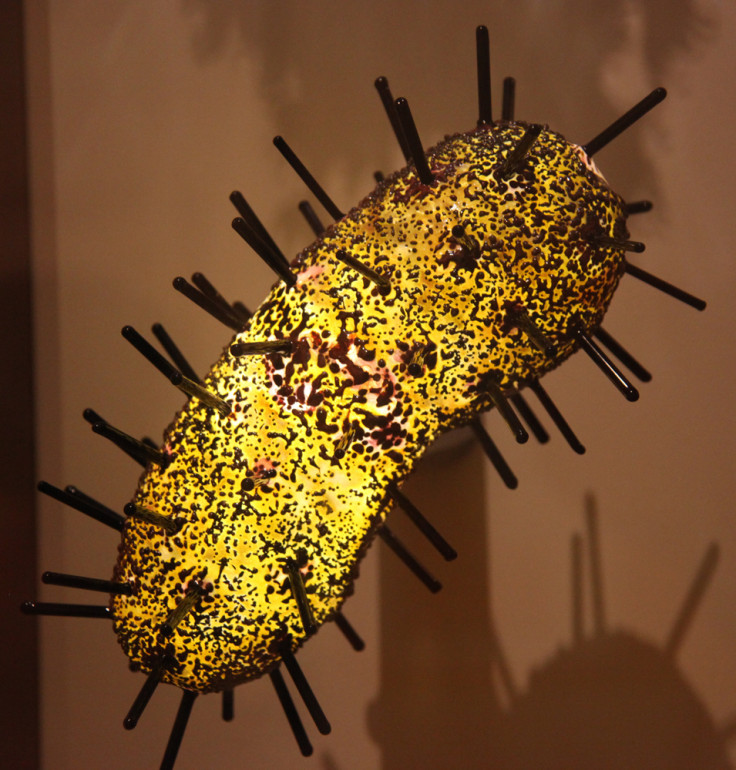

Th plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis – often transmitted by rodents - and is one of the deadliest infectious diseases known to men. It is often considered to be a historic disease, confined to the past, with the three main worldwide outbreaks occurring during the Roman Empire, in the middle Ages and 19<sup>th century.

Yet, Yersinia pestis is still present in animal reservoirs around the world, and some cases are regularly reported in Latin America and Africa. Understanding the way plague is transmitted and the damages it can cause is thus still relevant today. By studying the Eyam outbreak scientists hope to increase their knowledge of plague epidemiology.

Lower mortality rate

The researchers studied documents which had never been examined before, such as Parish registers and tax records. What they learnt was that the village's population was a lot larger than previously thought – with up 700 inhabitants instead of 350.

The records also indicated that during the fourteen months of the outbreak, between September 1665 and November 1666, 257 people died of plague. After excluding people who died from other causes and infants, the scientists say the plague mortality rate in Eyam was 37%, much lower than the 75% estimated in the past.

Routes of transmission

Based on population data, death rates and tax records indicating household compositions, the scientists constructed a statistical model to plot rodent-to-human and human-to-human transmission.

Contrary to common beliefs that plague is mostly transmitted by rodents, they showed rodent-to-human transmission only accounted for a quarter of all infections, but for three quarters in the case of human-to-human contact.

Additionally, the force of infection was stronger for infectious individuals living in the same household compared with the rest of the village. Among other risk factors, being part of a poor household significantly increased the risk of disease, but such a risk also decreased with age.

The scientists believe these results can contribute to the current debate on the relative importance of plague transmission routes, and lead to better prevention in the event of future outbreaks.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.