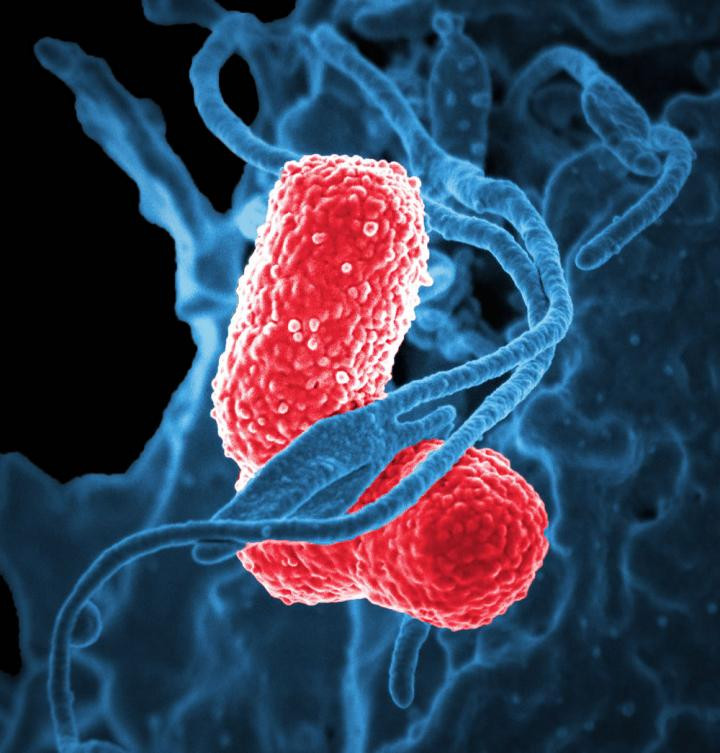

How a pneumonia-causing 'super bug' steals our iron and invades our bodies

A very resistant bacteria can take hold in the body by sending powerful little molecules to grab iron.

Scientists have identified new tactics used by K. pneumoniae to infect the human body. K. pneumoniae is one of the bacteria that can cause pneumonia – the disease currently affecting US presidential candidate Hilary Clinton – and it is particularly resistant to antibiotics.

When they infect their hosts, bacteria require iron for growth and proliferation. To defend itself, the human body had put some mechanisms in place to reduce the availability of iron to pathogens.

In this study published in the journal mBio, scientists have discovered that, in turn, K. pneumoniae has evolved to evade defence mechanisms, and to be more effective at grabbing iron and spreading in the body.

The bacteria has also figured out how to overcome all of the most potent antibiotics.

As the third-most-common cause of infections that arise in hospitalised patients, the findings could be used to research new drugs to fight K. pneumoniae and other "super-bugs".

Iron-grabbing molecules

Using mice infected with the bacteria, the researchers have studied small molecules known as siderophores, which are sent out by the bacteria to grab iron from the host's body during an infection. They have shown that these siderophores are much more powerful than the proteins produced in the body at grabbing and using iron to reproduce. They also produce a type of siderophore that our defence systems is unable to neutralise.

More problematic, K. pneumoniae has also become more efficient at invading the rest of the body beyond their initial point of entry. Indeed, in the process of sending out siderophores, the bacteria appears to activate a protein called Hif-1alpha, which normally helps our bodies respond to low oxygen or low iron. However, here, it worsens the infection by allowing K. pneumoniae to spread.

"This is a bacterium that has evolved new ways to get iron, and it turns out that the mechanism it uses also causes cellular stress during infections," explains lead researcher Michael Bachman from the University of Michigan. "That response triggers an immune response that tells our bodies to fight the infection, but it also activates a mechanism that allows bacteria to escape and travel to the rest of the body."

Fighting K. pneumoniae

These findings could open new avenues in order to fight the bacteria and prevent infections and pneumonia from developing. One of the option would be to develop strategies to prevent siderophores to be sent out, to neutralise their production. Another would be to use them to create a vaccine so that the immune system is trained to identify and attack them as invaders.

"This work provides us with motivation to target the production of siderophores, rather than just the uptake of them," concludes Bachman. "Now that we know that the bacteria cause cellular stress just by secreting them, we may be able to prevent these effects if we neutralise them."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.