Super-attractor implant catches cancer cells and stops disease spreading

An implant that can catch cancer cells and stop them from moving to other organs in the body has been developed by US scientists. The sponge-like device – a "super-attractor" – has been found to work in mice to detect cancer cells before they are visible elsewhere in the body.

The researchers, from the University of Michigan, designed the device to attract cancer cells that emerge in the bloodstream during early stages of the disease returning and before tumours appear in other parts of the body. Findings showed that it slowed the spread of cancer cells to the lungs by 88% compared to mice without the implant.

Their findings were published in the journal Nature Communications and the team hopes to develop a super-attractor implant that can be placed just beneath the skin of breast cancer patients. This would allow doctors to monitor it using a scan, then detect and treat any relapse sooner. They said it could also be used in women who are at a high risk for developing the disease.

Study author Jacqueline Jeruss said the idea for the implant came about because of the understanding that cancer cells do not spread randomly – they tend to be attracted to specific areas. This allowed the team to exploit this trait. Lonnie Shea, another author, explained: "We set out to create a sort of decoy − a device that's more attractive to cancer cells than other parts of the patient's body. It acts as a canary in the coal mine. And by attracting cancer cells, it steers those cells away from vital organs."

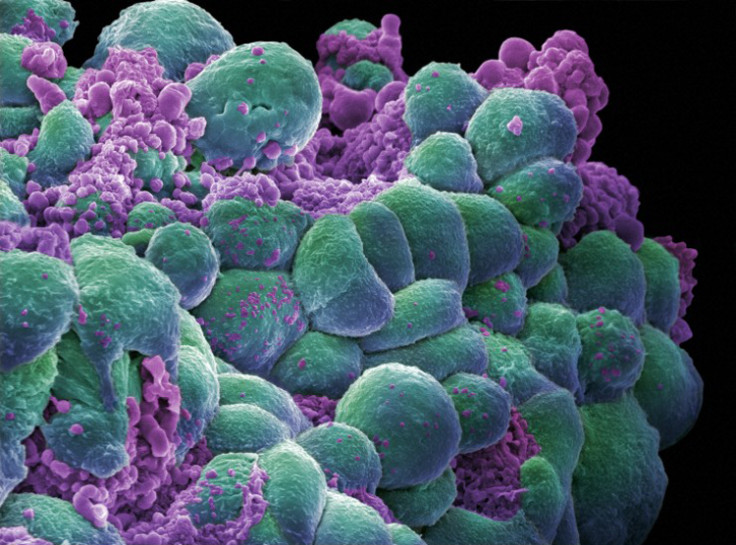

When the device was implanted into the mice, their immune systems responded as it would with any foreign object – sending cells to attack it. Cancer cells were then attracted to the immune cells in the device, where they took root in the sponge's tiny pores. They also did not group together to form a secondary tumour. Shea said: "We were frankly surprised to see that cancer cells appeared to stop growing when they reached the implant. We saw individual cells in the implant, not a mass of cells as you would see in a tumour, and we didn't see any evidence of damage to surrounding tissue."

The authors said it will be several years before the device can be used on patients, but they are hopeful it could be used for other types of cancer, including prostate and pancreatic cancer. They are now working to find out why the cancer cells were so strongly attracted to the device.

"A detailed understanding of why cancer cells are attracted to certain areas in the body opens up all sorts of therapeutic and diagnostic possibilities," Shea said. "Maybe there's something we can do to interrupt that attraction and prevent cancer from colonising an organ in the first place."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.