Mars Orbiter to seek out life on the Red Planet by detecting subterranean microbes

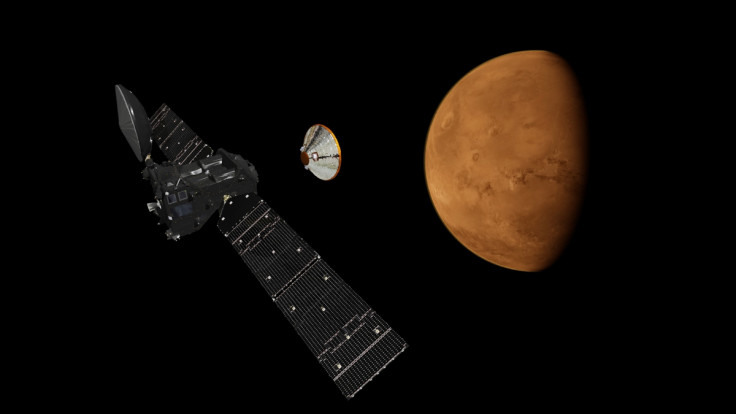

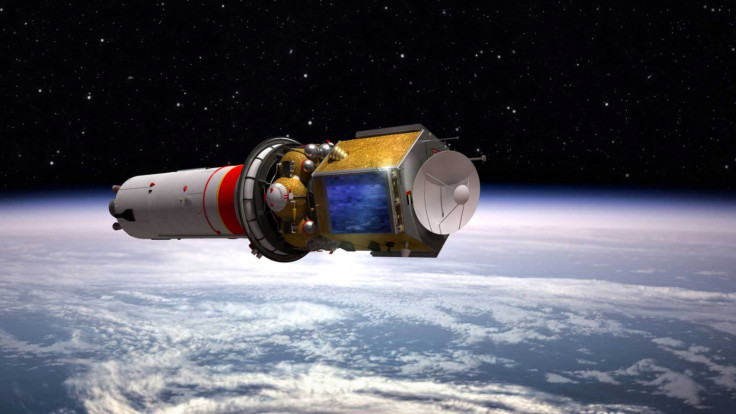

The European Space Agency (ESA) is to launch the Trace Gas Orbiter, a probe designed to analyse the Martian atmosphere for emissions of methane and discover what is producing them. The mission which commences next week, is the first stage in ESA's ExoMars programme. The second, in two years' time, will see the ESA flying a British-built robotic rover to the surface of Mars. It will then drill down 7ft into the Red Planet's surface to locate the methane-producing microbes.

"These missions are specifically designed to see if life has ever existed on Mars and if it still survives," said Professor Andrew Coates, deputy director of University College London's Mullard Space Science Laboratory.

"Methane is one of the key gases we are looking for. We know from other missions that it is coming from under the surface, and there are only two possible sources: geothermal activity or, mind-blowingly, some form of life, almost certainly microbial," he said in a Sunday Times report.

Fears of contamination from the Red Planet

If life is discovered on Mars, some experts worry that bringing back samples from the planet could endanger the Earth with unknown organisms. "If ExoMars finds life then our plans become far more sensitive and we will have to consider strict planetary protection protocols to minimise that risk," said Rolf de Groot, head of the ESA's robotic exploration programme.

Possible signs of rudimentary life has previously come from Nasa's Martian rovers, which found soil and rocks that could only have formed in lakes or rivers. Other exciting research shows that Mars once had a magnetic field to protect it from the sun's radiation – as the Earth has today.

"The emerging picture is that soon after Mars formed, around 4.6bn years ago, it was a very suitable place for life," Coates said. "The question is whether life, or its remains, might persist underground."

Hakan Svedhem, the ESA's project scientist for the Trace Gas Orbiter has stated that they have already detected methane on Mars but its behaviour is very strange, and further research needs to be done to understand it. The orbiter will also survey deposits of underground ice and water.

In 2018, the ExoMars rover's mission is to find buried microbes in the planet's core. It will be equipped with a new and improved drill which will enable the buggy to reach the soil layers where microbes could still survive. An onboard laboratory will look for the molecules of life, such as amino acids, lipids and nucleotides.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.