Milgram experiment: People ordered to give electric shocks are just as brutal now as they were 50 years ago

People still follow orders against their will and inflict pain on another person when told to by an authority figure.

Would you unwillingly deliver a painful electric shock to another person if a figure of authority told you to?

A variation of a psychological experiment designed in the 1960s to understand obedience to authority has been repeated in Poland, finding that people are equally willing to inflict pain today when told to by a figure of authority as they were 50 years ago. The study is published in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science.

The original experiment was invented by Stanley Milgram, a psychologist at Yale University, who wanted to understand how subordinates in the Nazi regime responded to authority. Were the atrocities of the Holocaust carried out in part because people were 'just following orders'?

Milgram intended to test the experiment on Americans before contrasting the results with Germans, to see if there was a difference in the two nationalities that made Germans more likely to follow orders that go against their values than Americans.

But he didn't get that far. American study participants – his test population – showed that they were surprisingly likely to continue administering shocks when they heard the person receiving the shocks screaming in pain, complaining of a heart condition or demanding to be released from the experiment.

50 years later

Milgram's experiment has been replicated with variations several times since it was first done in 1962. The study in Poland was the first time it had been repeated in a Central European country.

"As you may know, Polish people often think of ourselves are first to fight and first to resistance," study author Tomasz Grzyb of the SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities told IBTimes UK.

"We are extremely proud in our country, that we started the battle against communism, that we broke the Berlin Wall. That's only a cliché in our head, but many people think that we are like that. So we expected a slightly higher level of refusing [to give the shocks] than in other cultures."

How does the experiment work?

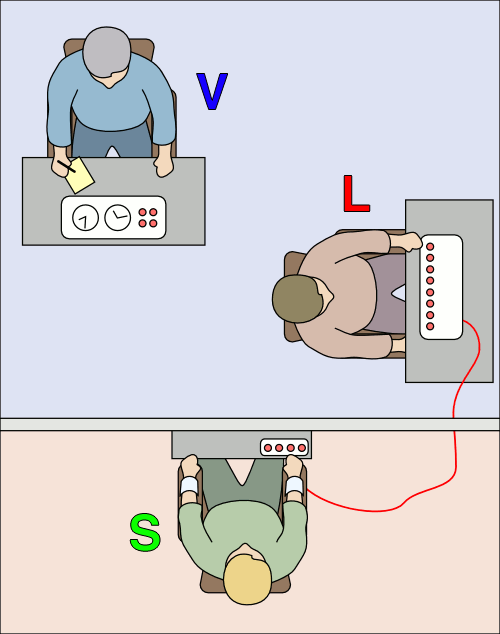

There are three people involved in the experiment: the experimenter, the teacher and the learner. The experimenter is a psychologist who is running the study. The teacher is an ordinary volunteer. The learner is an actor, who pretends also to be a volunteer for the study. The volunteer is told that the study is about memory and learning.

The volunteer and the actor draw lots, supposedly to decide who is the teacher and who is the learner. However, both slips of paper say 'teacher', to make sure that the volunteer becomes the teacher. The actor lies and says that their slip says 'learner'.

The actor leaves the room and the volunteer is told that they are going to sit in the next room. When the learner answers a question incorrectly, the volunteer has to administer an electric shock. The volunteer receives a test shock so they are given a sense of what they think they are giving to the actor. In reality, the actor is not shocked, but recordings of screams, complaints and demands to be released are played back for the volunteer to hear after administering a shock.

The shocks range from small to start with to very large as the experiment goes on.

If the volunteer says that they want to stop, the experimenter asks the volunteer to continue in increasingly strong terms each time:

- Please continue

- The experiment requires that you continue

- It is absolutely essential that you continue

- You have no other choice, you must go on

About 90% of participants in the study – who totalled 80, 40 men and 40 women between the ages of 18 and 69 – were willing to deliver the largest electric shock. The vast majority expressed a desire to stop during the experiment.

"Almost no one in our study was not satisfied with what he or she did. They always show regret. They told us, 'I don't want to do that, this guy is screaming, I would like to stop.' But they did not, they just pressed the next switch and the next one," Grzyb said.

New angles

There were, however, some differences between the Polish experiment and the original Milgram experiment – of which he did 24 different variations. Milgram's take is not considered ethical to repeat in full due to potential psychological trauma on the volunteers.

The Polish experiment included female actors as the learner, whereas in the original experiment the actor was always male. However, the sample size wasn't large enough to draw firm conclusions about the effects of gender on how the volunteer behaved.

Another difference was that the study stopped when the highest shock level was reached, not when the actor complained of a heart condition or suddenly ceased making any noises at all. Stephen Gibson at York St John University in the UK, a psychologist who studies obedience, said that the study should not be directly compared with the original Milgram experiments because of this.

"They've not introduced the sufficient pull for people to feel they want to get out of that experiment. The victim is kind of calling out in pain but not demanding to be released, so you don't have that withdrawal of consent form the apparent victim," said Gibson.

"In Milgram's experiment is crucial in letting someone realise they are inflicting harm on someone wanting to get out of that situation."

It's also been questioned whether this study design really does investigate obedience directly, or whether there is another factor at play. For example, study participants will frequently continue to press the buttons before they receive verbal orders from the experimenter to continue. When the experimenter issues orders, that's when study participants often finally refuse.

However, regardless of exactly what makes study participants carry on against their will, most of them do.

"It is surprising for me," said Grzyb. "When Milgram did his experiment he tried to spread the results as widely as he could because it was really important to tell people that we can behave in this way. That we can do cruel things, awful things to other people if there is someone saying they are taking all the responsibility.

"I was surprised that 50 years later we cannot shape our education system to explain to people how it is important sometimes to say no."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.