Faster gene editing tool can modify mosquitoes to stop transmitting diseases like malaria, dengue

Life science researchers at Virginia Tech have designed a quicker and more effective way to modify genes in organisms like mosquitoes. This is expected to accelerate efforts to develop novel mosquito-control or disease-prevention strategies.

The genome-editing method known as CRISPR-Cas9 has been used to delete and add genes to organisms. But often natural repair mechanisms are triggered that reduce opportunities for new sequences to be inserted into the genome.

The team overcame the hurdle by developing a process to silence the mosquito's DNA repair mechanism, so that the introduced changes become a permanent part of the mosquito genome.

Working with up to 5,000 mosquito embryos to investigate a single gene can now be done in a week compared to months required earlier, allowing faster and efficient ways to transform mosquitoes.

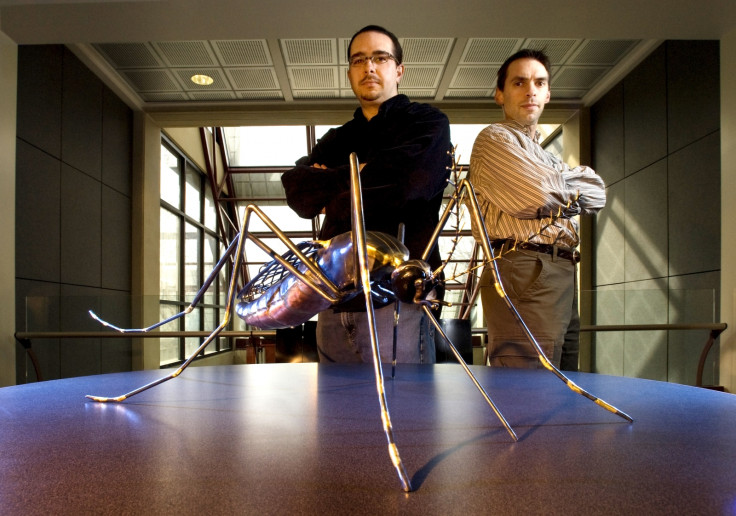

"We've cut the human capital it takes to evaluate genes in disease-carrying mosquitoes by a factor of 10," said Zach N Adelman, an associate professor of entomology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and a member of the Fralin Life Science Institute.

Eventually, research hopes to use the technique to edit disease-causing genes in people.

But for now it is restricted to mosquito research, and to strategically modify the genome of the insect that carries parasites and viruses and was called by Bill Gates as the "world's deadliest animal."

Mosquitoes transmit pathogens that cause malaria, dengue fever, and other high-impact diseases.

In 2013, malaria killed an estimated 584,000 people, most of them young children, according to the World Health Organization. The number of dengue infections globally stands at 390 million a year. Without due care, half of those infected die.

The current study has demonstrated the efficacy of the CRISPR system in mosquitoes. The researchers also improved the technique to increase the probability of precise insertion of DNA, making CRISPR more useful.

It is now possible for a scientist to find the genetic root of a mosquito phenotype.

"That's important for basic research into mosquito biology and applied research to control disease-vector mosquitoes," says Kevin M Myles, an associate professor of entomology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and a member of the Fralin Life Science Institute.

Dangers of the technique

When CRISPR arrived in 2012, it drastically reduced the time taken by researchers to rewrite an organism's DNA. Since then the technique has become much easier to use.

Recently, a group of researchers had called for a moratorium on the same technique over fears of its use in creating designer human embryos.

The CRISPR tool allows germline modification or genetic changes to embryos, eggs or sperm.

The fear is that germ-line engineering takes mankind on the dangerous path to superhumans and designer babies, for those who can afford it.

Unintended mutations are among the worries of those opposing the technology, saying that selected gene variants given an artificial boost could eliminate other versions of genes whose potential evolutionary importance scientists still have no idea of.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.