Nanoparticles Exposed in MIT Study Reveals Iron Hands in Velvet Gloves

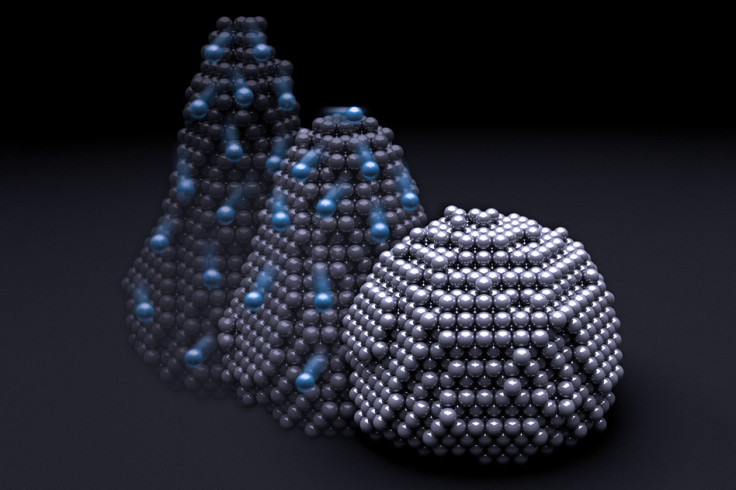

Nanoparticles have shown yet another unreliable side to their magical properties. A team at MIT has exposed shape-changing silver nanoparticles, which appear to be liquid droplets from the outside but retain a solid, stable crystal structure within.

In experiments conducted at room temperature (ruling out melting of the metal) they used the electron microscope to see that it was only the outermost layers comprising a thickness of one or two atoms that moved across the surface while deep inside the atoms stayed lined up like bricks.

The results should apply to many different metals, says Ju Li, senior author of the paper and the BEA Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering.

Used in applications ranging from electronics to pharmaceuticals to cosmetics, nanoparticles are desired to stay in a shape. The deformation discovered can be a serious barrier.

For example, if gold or silver nano ligaments are used in electronic circuits, these deformations could cause electrical connections to fail.

But having understood the phenomenon, researchers can work around this disadvantage by coating the nanoparticles with a thin layer of oxide which eliminates the liquid like wobbliness.

The new finding also comes as a roadblock on the road to improved mechanical strengths at small material sizes.

In most materials, mechanical strength increases as size is reduced. But now, as observed by Li, the transition from 'smaller is stronger' to 'smaller is much weaker' can happen around 10 nanometres size at room temperature and can be very sharp.

This is the size that microchip manufacturers are fast approaching as circuits shrink. They will now have to brace for "a very precipitous drop" in a nanocomponent's strength.

Nano magic

Materials have been known to drastically change properties at the nanoscale and become more reactive and magnetic. Nano gold particles for instance not only look red but are explosively reactive and catalytic.

Having greater surface area per weight, nanoparticles interact with their surroundings in ways that can render harmless substances toxic.

But their amazing properties also open up many opportunities in the field of medicine where they are used as drug delivery agents, able to cross cell barriers by virtue of their dimensions.

However, the dangers from their wide access as well as reactivity have also been a disadvantage.

At 10 nanometers width, they are less than one-thousandth of the width of a human hair and can easily lodge themselves in any organ within the body.

The results, published in the journal Nature Materials, come from a combination of laboratory analysis and computer modelling, by an international team that included researchers in China, Japan, and Pittsburgh, as well as at MIT, says a press release.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.