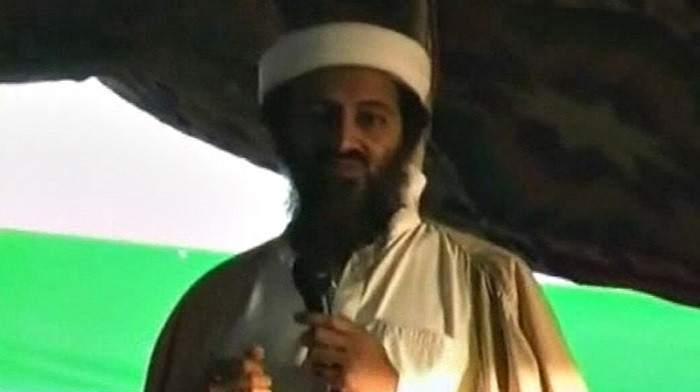

Osama bin Laden Killing Fails to End Americans' Thirst for Revenge

As the third anniversary of Osama bin Laden's assassination approaches, a study has found that his death has not satisfied many Americans' thirst for revenge.

The study, Vicarious Revenge and the Death of Osama bin Laden, looked at the reaction to news bin Laden had been killed by people in America, Germany and Pakistan.

Published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, researchers undertook three studies to find out if the vicarious revenge associated with Bin Laden's assassination led to feelings of satisfaction and re-established a sense of justice.

Even Americans who were not directly affected by the 9/11 attacks saw themselves as victims and were keen for revenge, the study found.

Respondents who felt a stronger sense of justice from Bin Laden's killing also showed a stronger need to take revenge further for those responsible for the attacks on the twin towers.

Study author Mario Gollwitzer, of the Philipp University of Marburg, told IBTimes UK: "We weren't really sure what to expect here. In cases of direct 'dyadic' revenge (A harms B, and B punishes A in return), we have some solid empirical evidence from earlier studies that revenge can - under certain circumstances - go along with a sense of psychological closure and a sense of justice achieved. This implies that revenge can sometimes close a chapter.

"In the present study, we seem to have found a case in which one act of revenge (the assassination of Bin Laden) did lead to a sense of justice achieved, but did not quench the desire to take more revenge. On the contrary."

The findings revealed that Americans who believed Bin Laden's death sent the message "don't mess with us" were the people who believed his death helped balance the scales of justice. Assassination, rather than death in any other way, also increased satisfaction.

The researchers found that while justice had been perceived as achieved, psychological closure had not. Gollwitzer said that revenge that provides closure and allows victims to "let go of their vengeful desires" can be healthy but the need for more revenge is not.

The final part of the study looked at how people from other countries viewed Bin Laden's death. Respondents in Germany and Pakistan, they found, felt less satisfaction over the death. This, the authors say, was due to people outside America observing the events of 9/11 as spectator rather than feeling they were involved.

"Americans are so much more content with the killing of Bin Laden because Americans conceptualised his death as an act of just desserts whereas Germany conceptualised it probably more as an act of deterrence.

"But that's speculation, we don't have the data to confirm this notion," Gollwitzer said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.