Preventing Dementia: Studying, Playing Music and Computer Games Key to Avoiding Alzheimer's

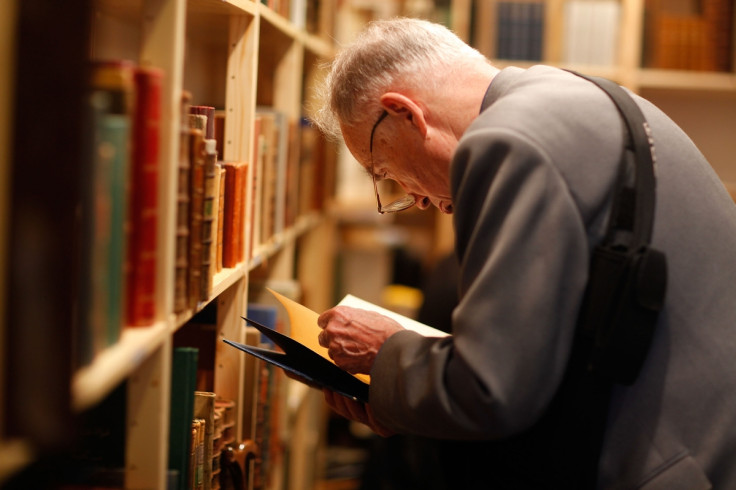

A lifetime of engaging in intellectually stimulating pursuits may significantly lower your risk for dementia later in life, according to new research.

Learning, studying, using the computer and playing music are all essential for preventing dementia, even in those with relatively low education and professional achievements if they adopt a mentally-stimulating lifestyle by the time they enter middle age.

"In terms of preventing cognitive impairment, education and occupation are important," said study leader Prashanthi Vemuri, an assistant professor of radiology at the Mayo Clinic and Foundation in Minnesota. "But so is intellectually stimulating activity during mid-to late life."

"This is very encouraging news, because even if you don't have a lot of education, or get exposure to a lot of intellectual stimulation during non-leisure activity, intellectual leisure activity later in life can really help," she said, in a report on CBS News.

For the study, the team tracked nearly 2,000 men and women aged between 70 and 89, who had enrolled in a Mayo Clinic ageing investigation between 2004 and 2009. Initial testing revealed that more than 1,700 of the participants were "cognitively normal" at enrollment, while nearly 300 had "mild cognitive impairment".

All participants were subsequently scored on their past educational achievements, while occupational histories were ranked by degree of intellectual complexity.

Participants completed questionnaires designed to pinpoint how much they engaged in intellectually demanding activities during the previous 12 months and from the ages of 50 to 65.

Each participant was also examined to see if they carried a variant of the APOE gene, considered the most significant genetic risk factor for late onset of Alzheimer's.

At the beginning of the study, mental functioning was lower among carriers of the gene, as well as those who scored lowest on education, career or activity.

However, APOE4 carriers who ranked highly in terms of education, occupation and activity routines saw their risk of dementia delayed by nearly nine years, compared with those whose with a low intellectual stimulation ranking.

The team also discovered that all participants who routinely engaged in intellectually stimulating activities in middle-age and later years saw their relative risk of dementia decline.

"Individuals with greater educational/occupational 'brain reserve' are more resistant to the effects of cognitive decline," Kevin Duff, a neuropsychologist from the University of Utah Health Care, told the Tech Times.

"However, if you don't get this reserve early in life, then it appears that cognitive stimulating activities in mid/late life can also have beneficial effects."

Results also showed that those with the lowest educational and occupational scores actually gained the most protection against dementia by taking part in intellectual activities.

"If you start early, your brain is probably sharper than starting later," Vemuri told The Atlantic. "But it's never too late, that's one strong message from the study."

The research was published in JAMA Neurology.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.