Scientists discover how to stop deadly Cryptococcus fungus from reaching the brain

The pathogen can hijack the immune system to spread throughout the body.

Scientists have discovered a new way of stopping a deadly fungal infection from spreading from the lungs of patients to their brains. The pathogen hijacks the immune system, and studying this process has provided valuable clues to develop ways for immune cells to fight it.

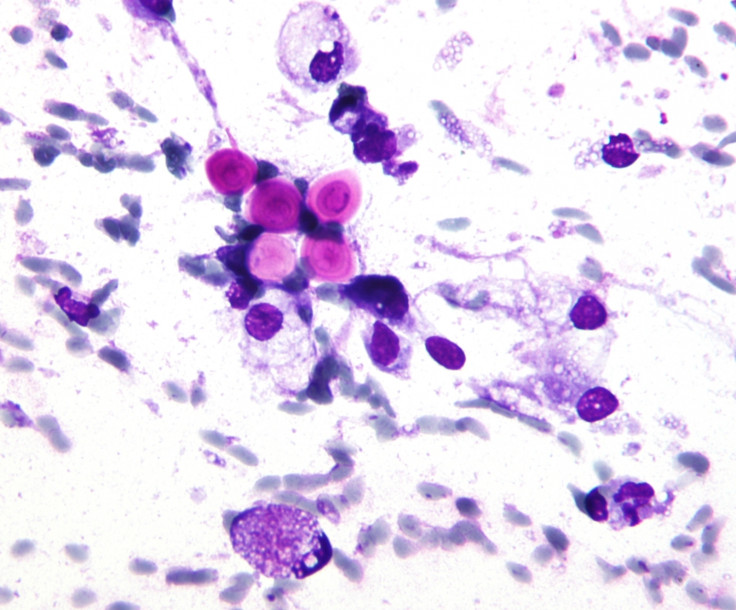

The fungal disease they studied is called cryptococcosis. It infects humans and animals after they breathe airborne spores from the fungus Cryptococcus, but it does not spread from person to person.

In healthy people, the fungus does not usually cause serious illness because their immune system can fight off the infection. But it is life-threatening for individuals with weakened immune systems, in particular those who are infected with HIV with no good access to effective treatment.

Although data on the topic is sparse, it is estimated that there are about a million case of cryptococcosis worldwide every year. Two thirds of those are fatal.

The infection is known to spread from the lungs to the brain by hijacking white blood cells called macrophages and surviving inside them. Macrophages are the first white blood cells to react when a person is infected, destroying the pathogens and alerting the rest of the immune system.

The problem with cryptococcosis is that the pathogen has evolved to survive inside the macrophages, using them to spread throughout the body, all the way the brain. However, scientists have found that a number of macrophages can succeed in ejecting the pathogen through a process known as vomocytosis.

In a study now published in Science Advances, researchers have studied this poorly understood mechanism further in the hope they would be able to find how it is controlled and how it can be used to stop the spread of an infection.

"We know that many white blood cells overcome the hijackers by throwing them out, using a mechanism called 'vomocytosis'. However, we don't know how vomocytosis is controlled. Our goal here was to understand the underlying mechanisms of vomocytosis. We wanted to identify the mechanisms that allow white blood cells to recognise and expel these hijackers," lead author Robin May at the University of Birmingham told IBTimes UK.

Working with zebrafish, the scientists first identified molecules that white blood cells used to control their behaviour. They then blocked the activity of these molecules one by one to see which ones controlled vomocytosis.

They found that one particular molecule called ERK5 could be manipulated to encourage white blood cells either to throw out pathogens better or to keep them inside and try to kill them for longer.

These results suggest that manipulating ERK5 could be a way to stop cryptococcosis from spreading in the body. The method could then be applicable to other infections in which pathogens also hijack white blood cells.

In a statement May concluded: "There are many diseases, not only Cryptococcosis, in which pathogens - bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites that can cause disease - survive by deliberately hijacking the immune system in this way. Longer term, our hope is that we will be able to develop therapies that target this process, such as drugs that would be able to limit an infection and prevent it from spreading from the initial site of attack."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.