Scientists have just designed a new tool to diagnose Alzheimer's disease earlier

About 44 million people worldwide have dementia.

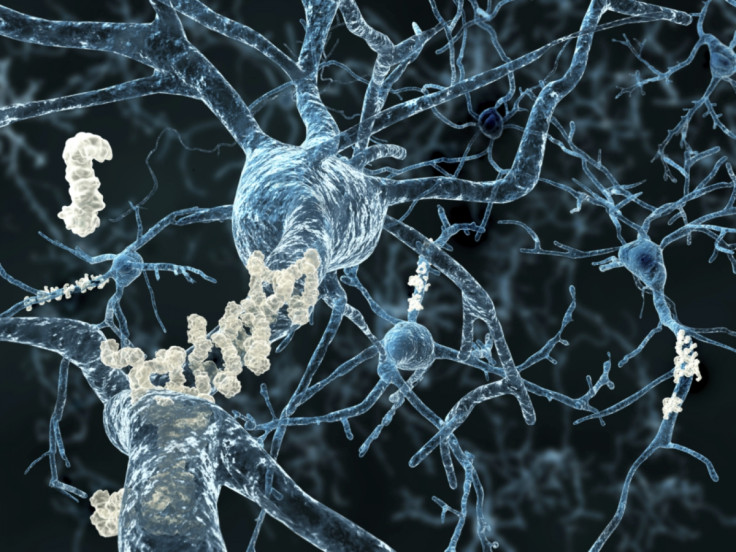

Scientists have established a potential new method to diagnose Alzheimer's disease and to assess the outlook for patients. They have figured out that changes to proteins found in the spinal fluid and blood are associated with the disease and can indicate its severity.

Dementia affects nearly 44 million people worldwide, and these figures are set to rise as the world's population ages. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer's disease.

At present, there is no single test that doctors can use to assess if someone is suffering from Alzheimer's disease, and what their prognosis is.

Doctors can indeed almost always tell if a person has dementia, but it often proves more difficult to determine the exact cause and to confirm whether it's Alzheimer's.

Developing novel diagnostics and biomarkers that can enhance Alzheimer's disease detection and management is thus a priority to make sure people are caught early on and can receive appropriate care and treatment.

Early diagnosis is all the more important so that available medication only treats symptoms of the disease and works best if they are taken in the very early stages of the disease.

In a study now published in the journal Science Advances, scientists show that the physical properties of the protein aggregates which are found in the cerebral spinal fluid and blood of patients are altered when they have the disease. "These properties can be used as a new class of 'physical biomarkers'," the authors write.

The scientists showed that as Alzheimer's severity increased, the proteins appeared to be longer, more rigid and more clustered.

Designing an algorithm

Next, the scientists used an algorithm designed to rate the severity of illness. The algorithm combined information about these new biomarkers and about several other factors typically used to diagnose Alzheimer's disease, such as scores from cognitive assessments of patients.

Using the algorithm in this way, the scientists found that they could identify disease stages and progression.

"With a tool like this you may predict how fast this disease will go, and currently we can't do that - we just know everyone is different," lead author Mingjun Zhang said. "Looking at multiple indicators of the disease all at once increases the reliability of the diagnosis and prognosis."

Of course, this is only an experimental tool at the moment, and so it is not yet ready for clinical use. But there is hope that it could radically change patients' experiences in the future, by helping to diagnose them early and with more confidence, and by giving them a more precise idea of their prognosis.

"Improved diagnostic tools could help doctors sort out more quickly which patients have Alzheimer's disease and which are experiencing cognitive decline for other reasons," co-author Douglas Scharre said.

The scientists also think that this diagnostic tool could also help speed up the discovery of a new treatments - in particular treatments that might work for people in the later stages of the disease. Indeed having an easily observable biomarker that changes quickly over time could help scientists to monitor the impact of the experimental treatments they want to test.

"A biomarker that shows that in three months, or three weeks even, that this drug is not doing a darn thing or is slowing down the disease will help us to not waste time in finding better treatments," Scharre said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.