Sea sponge inspires cancer drug without the toxic side effects of chemotherapy

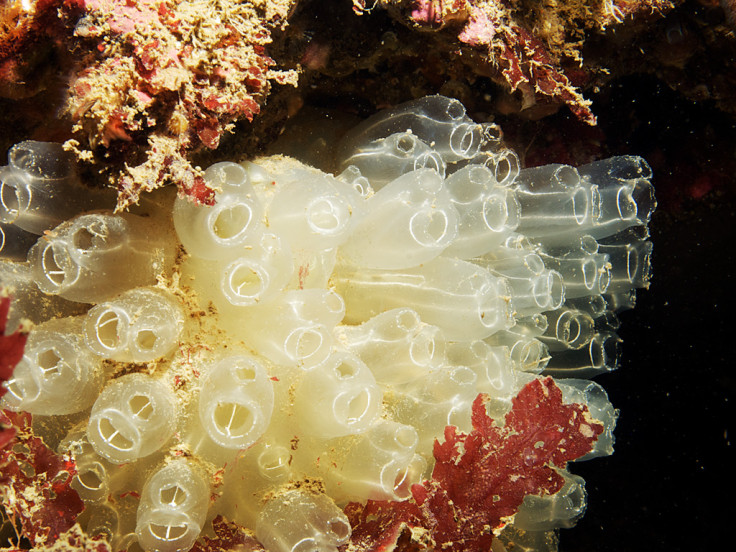

Synthetic version of rare compound from Diazona angulata used to treat leukaemia, breast and colon cancer.

A rare toxin produced by a sea creature has inspired a new cancer drug that fights the disease without the side effects of chemotherapy. The synthetic compound developed by scientists was found to me more effective at treating leukaemia, breast and colon cancer in rodents – and with far less toxicity.

The toxin produced by the sea sponge Diazona angulata was isolated by scientists. This substance, diazonamide, prevents cell division. UCLA's Patrick Harran who led the latest study published in Science Translational Medicine, began studying diazonamide in 1991.

After a decade of work, he and his team managed to re-create the compound in the laboratory. In 2007, they discovered it prevented cell division without the side-effects of chemotherapy.

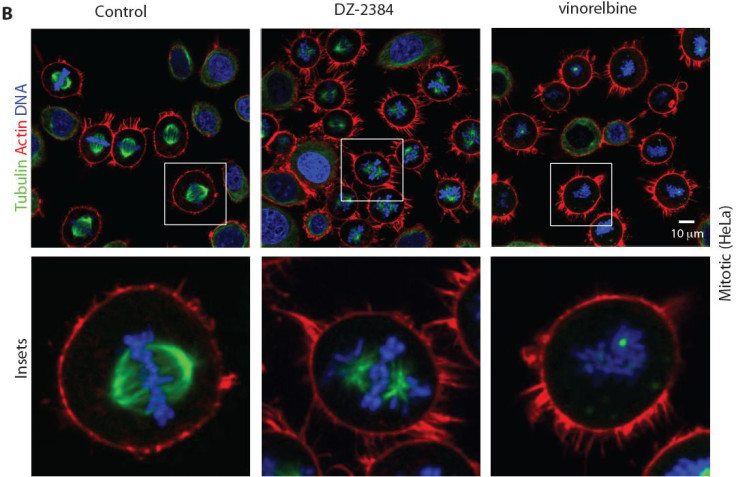

From this, Harran and colleagues have produced a synthetic version of the toxin DZ-2384 - which is more potent and lasts longer than natural diazonamide. They then combined it with the chemotherapy drug gemcitabine.

To test its effectiveness, researchers grew or implanted hundreds of tumours in mice and rats, representing different types of cancer. They tested DZ-2384 against conventional therapies.

Findings showed that the tumours in rodents being treated with DZ-2384 shrank as much or more than with traditional treatments. It was found to be effective in models of leukaemia, pancreatic, colon and breast cancer.

They also experienced fewer side effects - specifically, rodents showed far less peripheral neuropathy. This is a type of nerve pain that often affects people being treated with chemotherapy drugs and can be so severe, physicians end up stopping treatment.

Concluding, the team said DZ-2384 offers "potent anti-tumour activity" in multiple types of cancer while offering an "unusually high safety margin".

Harran said that he hopes to begin clinical trials on humans within two years: "We have good reason to expect that human clinical trials of DZ-2384 will show that, at doses effective for treating a person's cancer, there will be much less risk of the peripheral neuropathy that can force clinicians to stop treatment," he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.