Seasonal Protection against Malaria Could Save Thousands of Life Every Year: Study

Giving young children medicine once a month during the rainy season to protect them against malaria could prevent tens of thousands of deaths each year in some areas of Africa, according to new research.

A team of scientists analysed the potential impact of a new strategy to control malaria in Africa which takes a similar approach to that used to protect travellers going to malaria-endemic areas and found that even with moderate levels of coverage it could lead to significant public health improvements.

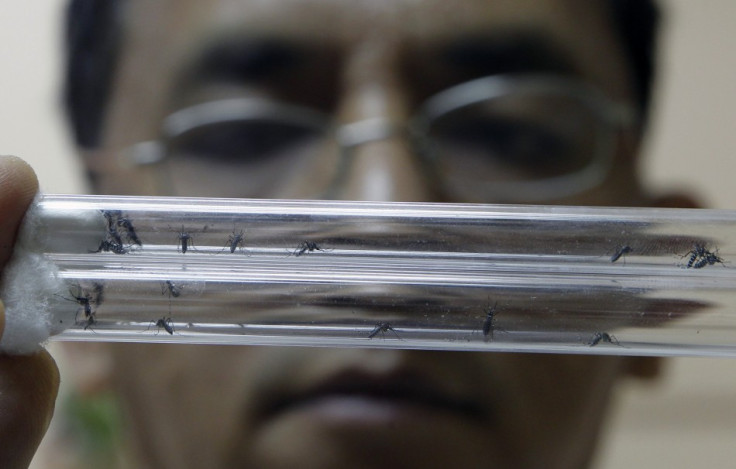

Malaria experts see this new approach, called seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), as an exciting new tool in the fight against malaria. The study highlights the areas of Africa where this approach could be used most effectively and will assist deployment of this new control measure where it is needed urgently.

The study, published in Nature Communications, was led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and involved a collaboration of researchers in the UK and Africa.

In some parts of Africa, malaria is only a major problem for a few months of the year during and immediately after the rainy season. In these areas, providing monthly courses of a cheap antimalarial drug combination (sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and amodiaquine) to young children during the malaria transmission season when they are at highest risk has been shown to prevent approximately 80 percent of severe and uncomplicated malaria cases.

It has been found that large-scale administration of antimalarial medicines once a month on repeated occasions can be carried out successfully, that it is very safe and that it provides protection even if children are sleeping under insecticide treated bed-nets. Currently, the main approaches to malaria control are use of insecticide treated bed-nets and spraying of homes with insecticide, combined with prompt diagnostic testing and effective treatment of malaria patients with artemisinin-based combination therapies.

Combining satellite maps of rainfall with information on the malaria burden in different areas of Africa, the researchers identified the regions where seasonal malaria chemoprevention would be useful and cost-effective. The largest impact would be in countries of the Sahel and sub-Sahel, a wide-belt of Africa ranging from The Gambia and Senegal in the West to parts of Sudan in the East. Key countries are Nigeria, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali, where approximately 14 million children under five are at risk in areas suitable for this approach.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.