Want Protection From Weapons of Mass Destruction? Weave Carbon Nanotubes into Your Clothing

Scientists from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the US have found a way to neutralise chemical weapons like Sarin nerve gas by weaving carbon nanotubes into clothing.

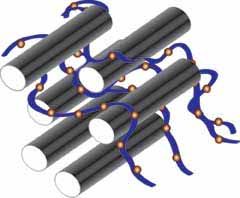

Nanotubes are special molecules that resemble grey cylinders. When these cylinders are combined together with a copper-based catalyst, they have the ability to break apart the key chemical bond in a class of nerve agents, rendering them less harmful.

Their research, entitled "Functionalised, carbon nanotube material for the catalytic degradation of organophosphate nerve agents" is published in the journal Nano Research.

Sarin gas is part of a group of deadly nerve agents called organophosphates and was used in the 1995 Tokyo subway attack, which killed 13 people, severely injured 50 more and caused temporary vision problems for almost 1,000 people.

When inhaled or absorbed by the skin, the nerve agent causes a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine to build up in the central nervous system, causing muscles in the body to seize up.

When the muscles that we use to breathe seize up, such as the diaphragm, the effects of the gas prove fatal.

Classified as weapons of mass destruction, organophosphates can even be re-released from clothing, if it is not properly decontaminated, so to protect themselves, the researchers performed their experiments using a "mimic molecule" which has a chemical bond identical to that of organophosphates.

The researchers attached the catalyst molecule to the nanotubes and then placed the complex onto a piece of paper. When they placed the piece of paper in a solution containing the mimic molecule, the complex was able to break the chemical bonds.

"The solution was initially transparent, almost like water, but as soon as we added the paper, the solution started to turn yellow as the breakdown product accumulated," said study co-author John Heddleston.

"Measuring this colour change over time told us the amount and rate of catalysis. We began to see a noticeable difference within an hour, and the longer we left it, the more yellow it became."

More research still needs to be done before nanotubes can be added to clothing, however, in order to make the protection as strong as possible.

Study co-author Hight Walker said: "We'd also like to find ways to make the catalytic reaction go faster, which is always better, but our research group has been focusing on the fundamental science of nanoparticles for years, so we are in a good position to answer these questions."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.