World Cancer Day: Sudan's only breast cancer clinic raising £100,000 to replace vital equipment

KEY POINTS

- The Khartoum Breast Cancer Care Centre has changed attitudes towards breast cancer in Sudan.

- The clinic screens around 200 women a week.

When the Breast Cancer Care Centre in Khartoum opened eight years ago, it became the only facility in Sudan dedicated to treating women with the deadly disease. Since then, it has transformed attitudes towards breast cancer in a socially conservative nation and saved thousands of lives in the face of US sanctions.

Now, to mark World Cancer Day, the team behind the centre has launched a crowdfunding campaign for £100,000 to replace the clinic's mammography machine - the only one in the whole of Sudan. The equipment is used to screen around 200 women a week but recently broken down for ten weeks.

The equipment is vital as it enables clinicians detect even the smallest signs of the potentially deadly disease before it spreads and becomes harder to treat. Women can travel long distances to attend the centre. If they arrive and it is broken, their travel fare will have been wasted, they may be put off front returning, and could delay a life-saving screening. Any day without the mammography machine risks lives.

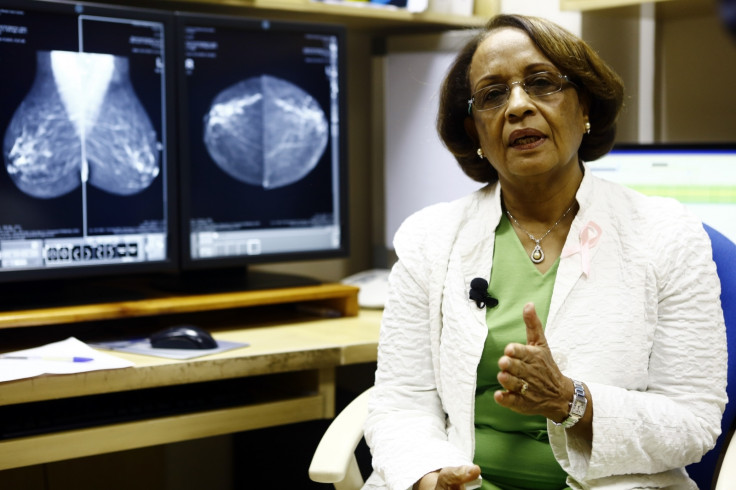

"10 weeks is a hell of a lot of time for the machine to break down," Dr Hania Fadl, a Sudanese radiologist and founder of the centre, who worked in London for two decades, told IBTimes UK. "We see 40 cases a day and it's going up all the time. In the beginning it was maybe 30. The problem is you can't see new patients without the machine, and you can't tell those who come for a follow-up when to come back. Some of them really travel a long distance."

"Mammography is the only internationally recognised modality for breast cancer screening," she explained.

"It enables you to look for and see lesions that doctors can't feel. We can then do a procedure where you use a wire to take them out. And even if a woman comes in with a big lesion you have to do a mammogram because you never know what's happening in the other breast, or she might have two smaller lesions in another part which you can't feel. Or there may be lesions on the other side. So it's very important."

As well as the mammography machine, which costs over £300,000, the centre hopes in the future to buy a CT scanner to check the disease hasn't spread before women undergo surgery.

Opening in 2010, the facility had its work cut out. Not only was access to screenings and treatment for breast cancer expensive, but women's health was a taboo subject. Educating women about breast cancer and getting them through the centre's doors in the first was as important as filling it with state-of-the-art equipment.

US sanctions - imposed because of Sudan's links with terrorism and human rights violations - posed another obstacle. All of the centre's equipment is manufactured by a US company, meaning it was affected by a ban on international money transfers, and restrictions on medical equipment. When the mammography machine broke down for ten weeks on a separate occasion in 2014, Dr Fadl took her fight to Congress - and convinced a government body to exempt medical equipment from the sanctions.

The next challenge was spreading the message that breast cancer is not a death sentence, and is a treatable disease.. The centre's outreach programme, which has even targeted women in Darfur in the west, has taught women how to self-check, and broken down the stigma around the disease which affects such an intimate area. The KBCC now sees 24,000 women a year.

"At the beginning women were reluctant to speak about their experiences. Now if we have an event they all want to hold the microphone. They talk about it and they don't mind."

"People are more open and we get more cases where the cancer is small because they have done the breast examination at home. Once they feel something they come in, and we now have cases with lesions as small as 1cm.

"We let survivors talk to women to reassure them." Dr Fadl says one of the most memorable cases she has dealt with was of a woman called Instir, who attended the centre six months pregnant. The centre saved both of their lives.

"We have started sending out groups of 20 or 30 doctors, medical students, and midwives - midwives are really important in rural communities because they have good connections - we give lectures as well as hands on workshops, and give out leaflets.

"We go and visit ladies at their work, we go to factories, companies, banks, and we talk to them there and answer all their questions. We even visit housewives."

"These women have the right to have proper treatment," she added. "It's the same treatment and drugs and medicines and to not have that available I think that is really unfair and cruel. Why can a woman in the West have that, but because of sanctions or whatever a woman in Sudan can't?"