Your liver swells and shrinks by almost half its size every day

The whole liver grows in size to cope with extra stress when we eat and drink.

The liver has a remarkable ability to grow to one and a half times its size before shrinking back on a daily basis, scientists have discovered.

After the skin, the liver is the largest organ in the human body. It has a huge range of vital functions, from filtering out toxins such as alcohol to making bile.

Now scientists have discovered that the size of the liver is closely tied in to the workings of the body clock, also known as the circadian rhythm. The results are published in the journal Cell.

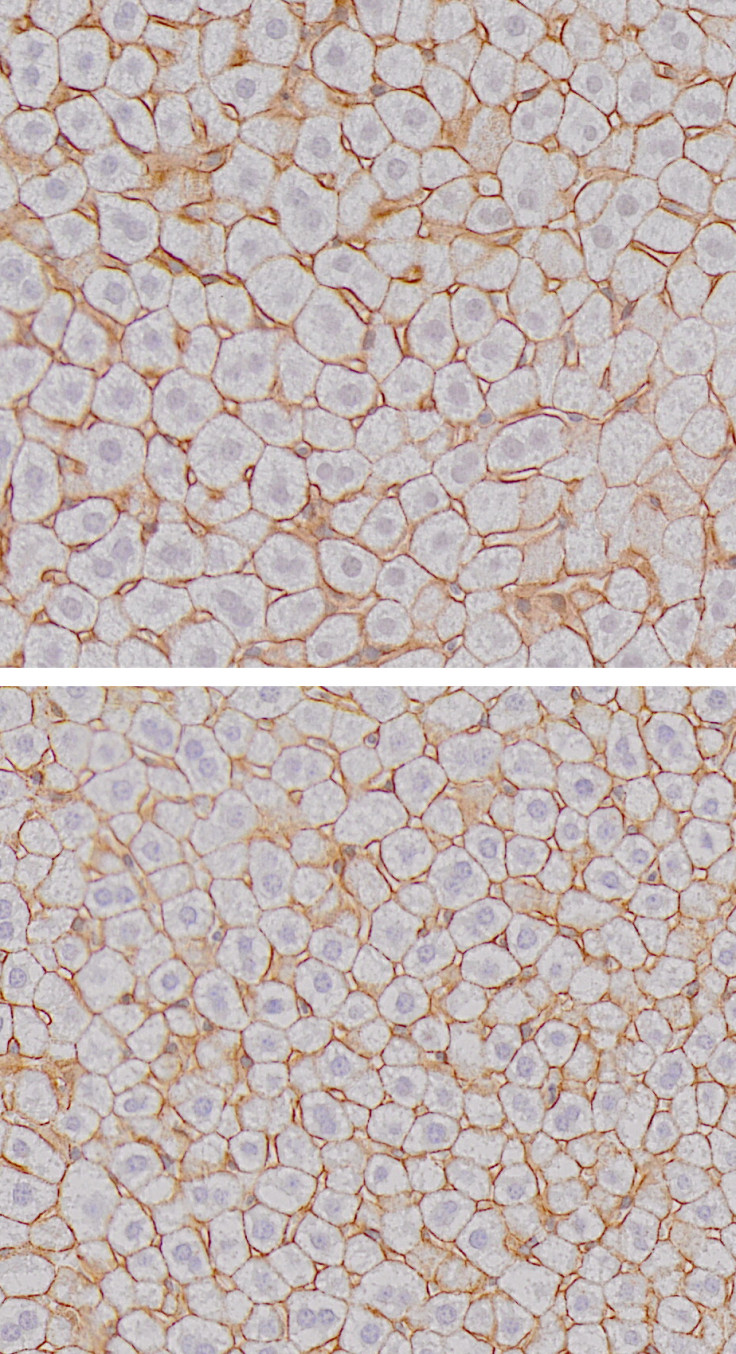

A study in mice has found that the mass of the whole organ, the size of the individual liver cells and the amount of protein in the liver varies hugely throughout the day. The liver is at its largest and most active when the mice were most active. As mice are nocturnal animals, this meant that their livers were bulging by the early hours.

"We saw the biggest difference in the night, an up to 45% increase. I would expect that this is true in most mammals, but exactly what the effect will be in humans we don't know yet," study author Ueli Schibler of the University of Geneva told IBTimes UK.

The change in mass is thought to be to help the mice deal with the extra activity – the more food the mouse eats, the more work the liver has to do to keep up.

"The liver gets all the bad stuff from the food and has to deal with that," Schibler said. "It's possible that it's not sufficient to have a liver the size of the resting phase at this point."

But when mice had their body clock disrupted, the liver lost its ability to grow and shrink. Mice that were fed during the day had a constant liver size, even though they were eating the same amount of food as mice in the ordinary nocturnal rhythm.

"This may contribute to the health problems associated with shift work. When we eat at the wrong time, the liver doesn't oscillate," Schibler said.

Previous studies in humans from the 1980s showed that the liver in humans also changes size, although the measurements were not on such a fine scale. These would require invasive measurement methods, Schibler said.

"But it would be very interesting to do that, and measure the oscillations of the human liver around the clock."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.