3I/ATLAS Anti-Tail Could Prove Interstellar Object Is A Comet, Avi Loeb Reveals

Avi Loeb investigates whether interstellar visitor 3I/ATLAS is a natural comet or a sign of alien tech.

The night sky has always been a place where we can see our biggest mysteries. But the arrival of the third known interstellar visitor, 3I/ATLAS, also known as C/2025 N1, has sparked a debate that goes all the way from Harvard to the farthest reaches of our solar system. The Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System in Chile first saw this visitor on July 1, 2025. It is moving at a mind-boggling 58 kilometers per second, which is much faster than its predecessors, 'Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov.

This mysterious traveler is on a one-way, hyperbolic path past our sun, and it has a defiant 'anti-tail'—a striking jet of material pointing straight at the sun—that refuses to stay quiet in the world of traditional astronomy. Is this just an old piece of junk from a faraway star system, or could it be the smoking gun for a technological presence in our own backyard?

Researchers are scrambling to find answers about the object that was captured in amazing detail by a small 0.2-meter telescope in Belgium in December 2025. The fact that such a small, ground-based instrument could capture these details highlights the object's surprising luminosity as it passed 270 million kilometres from Earth.

By applying a Larson–Sekanina rotational gradient filter to images from 19 and 27 December, astronomers revealed a pronounced anti-tail stretching several hundred thousand kilometres in the sunward direction. This feature is not just a visual curiosity; it is a physical puzzle that challenges our understanding of how interstellar objects behave when they meet the heat of a foreign star.

The Physics Behind The Mysterious 3I/ATLAS Anti-Tail

To understand why this sunward jet is so significant, one must look at the invisible war being waged between the comet's own outgassing and the relentless pressure of the solar wind. Under a purely natural scenario, 3I/ATLAS is assumed to be a conventional comet, with its activity driven by the sublimation of carbon dioxide (CO₂) ice. At a distance of roughly 2 AU from the sun, where surface temperatures hover around 200 K, the gas is expected to rush away from the nucleus at a speed of approximately 0.2 km/s.

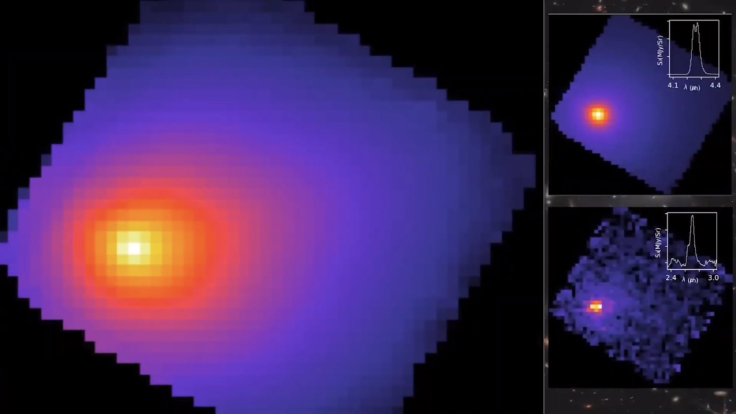

Recent data from the James Webb Space Telescope suggested a pre-perihelion mass-loss rate of about 150 kg/s, a figure likely to have surged to around 500 kg/s as the object made its closest approach to the sun. While this gas is powerful enough to loft dust grains—specifically those around 10 microns in size—it eventually hits a wall. Harvard professor Avi Loeb, who famously detailed the search for alien life in his book Extraterrestrial, points out that this gas should 'stall' when its ram pressure is equalled by that of the solar wind. In simpler terms, the solar wind acts as a physical barrier, pushing back against the comet's emissions.

Numerical calculations suggest this stopping point occurs at roughly 5,000 kilometres from the nucleus. This matches the bright coma seen in Hubble Space Telescope imagery. Beyond this boundary, the solar wind should effectively sweep the gas away. Therefore, if 3I/ATLAS is a natural comet, the long anti-tail we see reaching across the void should be composed entirely of larger dust grains, effectively 'devoid of streaming gas.'

Could 3I/ATLAS Harbour Secrets Of Alien Technology?

The intrigue deepens when we consider the alternative. If 3I/ATLAS is not a simple rock, but rather a craft propelled by something more advanced, the rules of the game change entirely. The analysis notes that a technological propulsion system would produce much higher exhaust velocities, allowing the gas jet to punch through the solar wind for much longer distances. Loeb, who also leads the Galileo Project, argues that we must remain open to 'anomalies' that do not fit the standard icy-rock model.

If the jet were driven by a chemical thruster with an exhaust speed of 5 km/s, the gas could remain coherent out to 25,000 kilometres. If it were an ion thruster—the kind of tech we use for deep-space missions—the gas could stretch as far as 100,000 kilometres sunward. This creates a clear, binary test for the object's nature. By mapping molecular species like CO₂ or CO along the jet axis, we can determine the truth. A sudden drop-off at 5,000 kilometres points to nature; a persistent trail points to 'a different, potentially technological, origin.'

The scientific community is now calling for an all-hands-on-deck approach. From the Keck and Very Large Telescope to the James Webb Space Telescope and the upcoming SPHEREx mission, the race is on to map the gas and dust of 3I/ATLAS. Observatories in Tenerife and Hawaii are already providing high-resolution data to feed into this global investigation. As we wait for these definitive measurements, the world watches, wondering if this visitor is a message from the stars or just another piece of cosmic drift.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.