Amazon tribe that has never had contact with other humans has antibiotic resistance genes

An Amazon tribe that has never before come into contact with other humans has been found to have antibiotic resistance genes, possibly suggesting these may be a natural feature of the human microbiome.

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most significant threats to public health, with experts warning of a looming apocalypse.

An international team of researchers found the Amerindian villagers have what is possible the highest levels of bacterial diversity ever reported in a human group, suggesting that westernisation is associated with the loss of bacterial diversity.

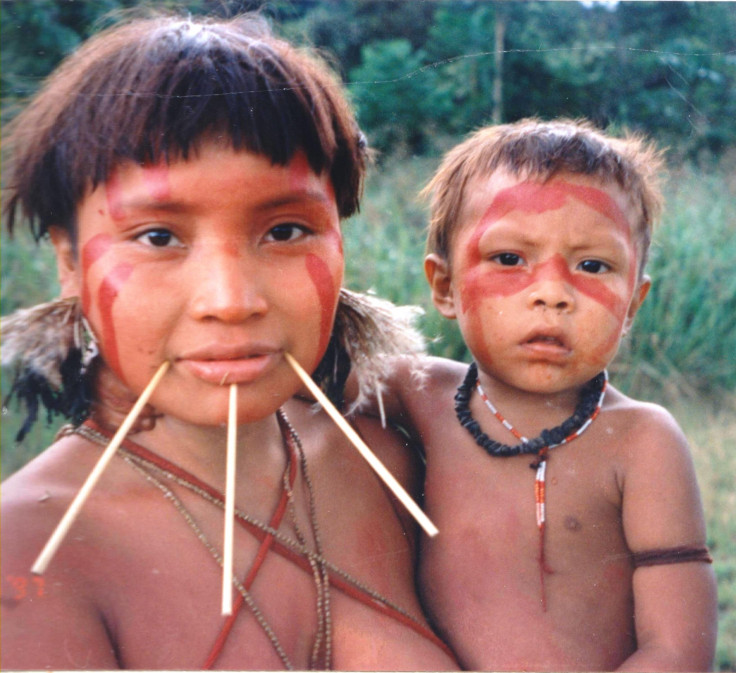

They were an isolated tribe of Yanomami Amerindians living in a remote mountainous area in southern Venezuela. The villagers live semi-nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyles and have done so for 11,000 years.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, used microbial DNA collected from villagers during a medical mission, with scientists collecting faecal, skin and mouth swab samples from 34 individuals.

The villagers said they had never seen non-Yanomami people before, however they had seen planes and helicopters, knew the word "medicina" and had some non-traditional products such as T-shirts and cans.

Researchers sequenced and analysed the DNA and found significantly higher bacterial diversity compared with US populations and two other non-Western groups with limited exposure to Western practices.

Along with the bacterial diversity, scientists were also extremely surprised to find genes for antibiotic resistance, as the Yanomami have presumably never been exposed to commercial antibiotic drugs.

Erica Pehrsson, one of the study authors, said: "These people had no exposure to modern antibiotics; their only potential intake of antibiotics could be through the accidental ingestion of soil bacteria that make naturally occurring versions of these drugs. Yet we were able to identify several genes in bacteria from their faecal and oral samples that deactivate natural, semi-synthetic and synthetic drugs."

Thousands of years before people started using antibiotics to stop infection, soil bacteria started to produce naturally occurring antibiotics to kill competitors. Microbes then evolved defences to protect against the antibiotics – getting resistance genes.

More recently, the use of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture has sped up this process, meaning strains of disease that are harder to treat have emerged and pose major health risks.

Researchers do not know if the diversity of bacteria improves or harms health but said there is growing evidence showing a link between decreased diversity and immunological and metabolic disease like asthma, diabetes and allergies.

Most human microbiome studies focus on Western populations, so researchers think access to people who have never been exposed to antibiotics could be key to finding new therapies for some diseases caused by imbalances in the microbiome.

While studying the DNA, scientists found the antibiotic resistance genes of the Yanomami people could resist semi-synthetic and synthetic antibiotics – they could resist drugs that the microbes have never encountered before, possibly indicating cross-resistance.

"These include, for example, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, which are drugs we try to reserve to fight some of the worst infections," said study author Gautam Dantas. "It was alarming to find genes from the tribespeople that would deactivate these modern, synthetic drugs."

However, the researchers also say the huge diversity of the microbiome could possibly suggest populations living ancestral lifestyles could be holding a reservoir of microbes with therapeutic values for various modern diseases.

Gloria Dominguez, another author of the study, said the concerns over the dwindling bacterial diversity in Western populations was what drove them to undertake this research. She said: "We are a human society that exert compounded impacts on the microbiome from very early ages. And we are now having asked ourselves in perspective when we compare ourselves with these people, and realise how much diversity we have lost.

"And the challenge is to determine which are the important bacteria, whose function we need to be healthy and have a healthy educated immune system and a healthy metabolic system."

Dantas added: "By studying the resistome of this incredible, previously uncontacted, antibiotic-naïve human group, we are able to establish that antibiotic resistance is a natural feature of the human microbiota, just waiting to be activated and amplified after antibiotic use.

"This emphasises the need to ramp up our search for new antibiotics, because otherwise we're going to lose the battle against infectious diseases."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.