Celtic ancestors had worms: Intestinal parasites found at 2,000-year-old Switzerland settlement

Two thousand-year-old intestinal parasite eggs have been unearthed at the site of a Celtic settlement in Switzerland.

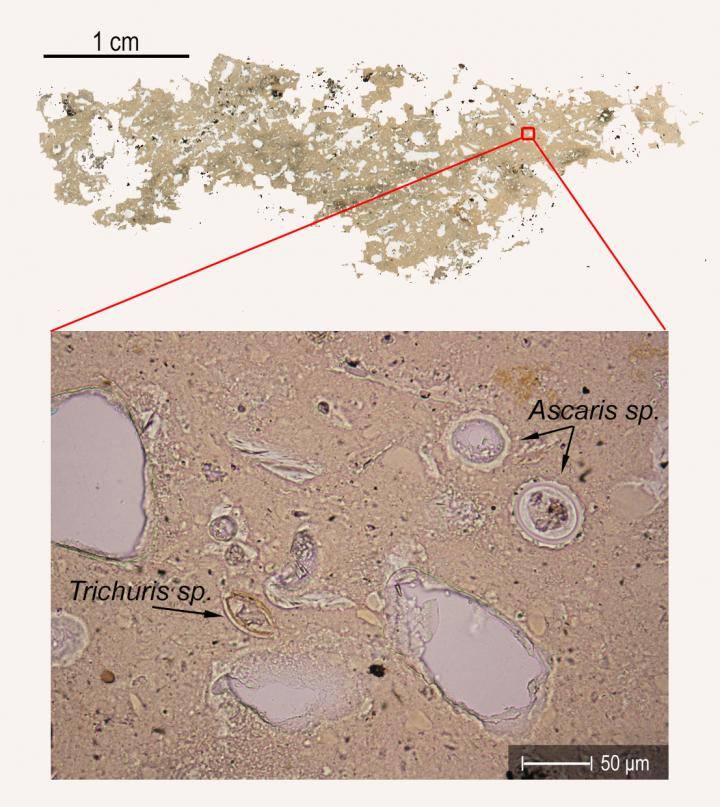

The parasites included durable eggs of roundworms, whipworms, and liver flukes.

Archaeologists from the University of Basel discovered the parasites in samples taken from the former Celtic settlement of Basel-Gasfabrik - the present day site of Novartis.

The area was inhabited around 100 BCE and is one of the most significant Celtic sites in central Europe. Researchers say their finding suggests the community lived in very poor sanitary conditions.

Eggs were discovered in the backfill of ancient storage and cellar pits from the Iron Age.

Parasites discovered

Roundworms infest the human gut where they live, feed and reproduce. They do not tend to cause any symptoms and are normally easy to treat. People normally see their GP after noticing a worm in their faeces. If lots of eggs are ingested, they can cause complications including bowel obstruction.

Whipworm is a round worm that causes trichuriasis when it infects the large intestine. Those infected may get abdominal pain, tiredness and diarrhoea. In children it can cause physical development problems. Whipworm is passed on through the faeces of infected people, normally when defecating outside.

Liver flukes are localised in the liver and are a type of flatworm that feed on blood. Transmission is normally through consuming contaminated plants or water. Symptoms include fever, itching, abdominal pain, a rash and cough. After the worm has matured, symptoms are related to the blocking of the biliary system – such as infection and jaundice. Worms can live up to 12 years.

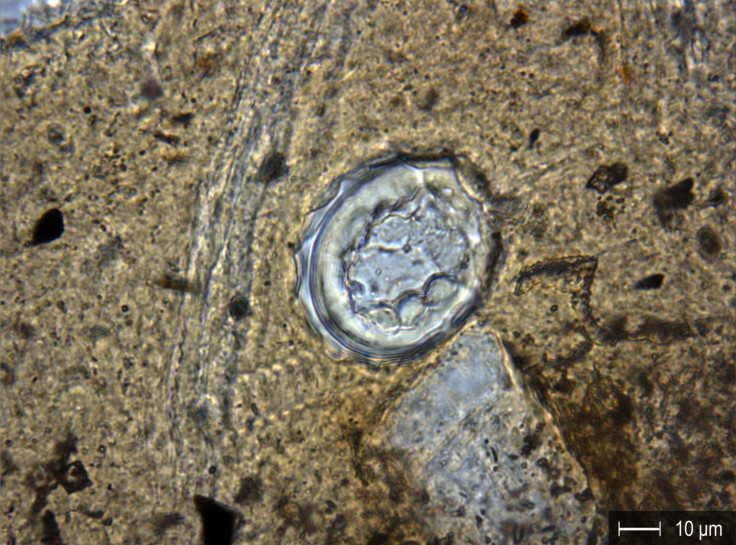

They were discovered using a geoarchaeology method, which was applied to thin sections allowing the eggs to be captured in their original settings.

These sections were prepared from soil samples embedded in synthetic resin – meaning researchers could work out the exact location and number of the eggs at their original site in the sediment pits.

Findings of the study provide clues into the diseases triggered by parasites at the settlement and suggested the inhabitants lived in poor sanitary conditions.

Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, researchers believe the parasites might have been brought into the settlement from the surrounding areas via livestock – at the time humans and animals lived side by side.

"The eggs of the Iron Age parasites originate from preserved human and animal excrement (coprolites) and show that some individuals were host to several parasites at the same time," the authors said.

"Furthermore, the parasite eggs were distributed throughout the former topsoil, which points to the waste management practiced for this special type of 'refuse'. It may, for example, have been used as fertilizer for the settlement's vegetable gardens."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.