Controversial placenta treatment could cure radiation poisoning after nuclear disaster

Macaques treated with placental stem cells had higher survival rate after being exposed to radiation, study claims.

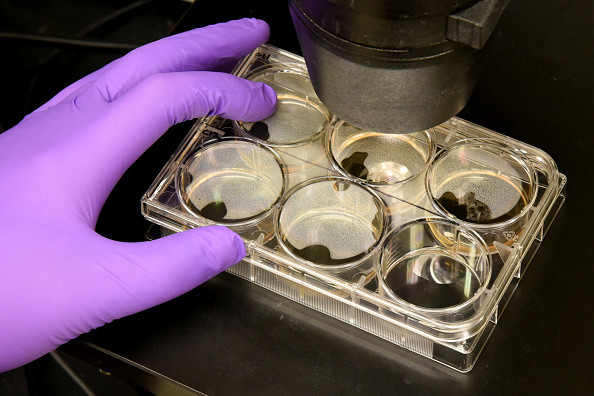

Stem cells from the human placenta are being trialled in the US as a potential therapy for acute radiation sickness in the event of a nuclear attack or accident.

When an incident like the Fukushima meltdown happens, or in the event of nuclear war, treatments for acute radiation sickness need to be distributed fast. It might not be immediately obvious who has been exposed to high levels of radiation and there may not be time to test for blood types for conventional treatments.

A drug trial being carried at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the US has found that placental stem cells could be a good candidate for treating acute radiation sickness.

The drug PLX-R18 uses donated human stem cells to replenish the red and white blood cells and platelets that are destroyed by strong radiation. The cells don't need to be matched by blood type, as placental stem cells have few biomarkers that could be detected and attacked by the body.

"They are quite primordial, they don't show all molecules on their surface and so they are less immunogenic. They are not really identified by the host as being alien – this is what helps the placenta in keeping the foetus unharmed," Arik Eisenkraft, director of homeland defence projects at Pluristem Therapeutics in Israel, the company that designed the therapy, told IBTimes UK.

The macaques in the study were given a potentially lethal dose of radiation and monitored for 45 days. They had an 85% survival rate if they were given between 4 and 10 million PLX-R18 cells per kilogram of body weight, compared with 50% in those that weren't given the therapy.

The study was small, on just 48 macaques. This means the results were not statistically significant – so in a wider population, the treatment may have no more benefit than a placebo, said John Hopewell a consultant radiobiologist at the University of Oxford.

"It is extremely dangerous to just use a single radiation dose level in experiments of this type, because the results can be misleading," Hopewell said.

The fine-scale data of the study has cannot be released because of the nature of the trial, a spokesperson for Pluristem said.

The results are now being taken forward to a larger animal study to be carried out by the NIAID. It is also set to be trialled on humans who have not had a full recovery after a bone marrow transplant.

If it is successful then the therapy could offer a promising and fast way to treat patients with acute radiation sickness. At the moment, no effective therapies exist, Hopewell said.

"Recovery is by bone marrow transplantation with plenty of time to get a good tissue match but even then cases fail.

"In the Chernobyl radiation accident a few cases were found where the bone marrow picture was such that a bone marrow transplant thought advisable, no idea how good the matches were in the time available."

PLX-R18 is now being taken forward to a larger animal study. It is also set to be trialled on humans who have not had a full recovery after a bone marrow transplant.

If the drug is found to be successful in the larger animal study, then it could be approved by the FDA without a full scale trial in humans, as such a trial would be ethically impossible to do.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.