Decarbonising Top Economies: Delay Tightens Screws on Planet's Climate

Tremendous technological effort will now be needed to limit global warming to two degrees by 2050. Nations of the world have hardly taken any step towards this goal, with many not even bothering to study the task.

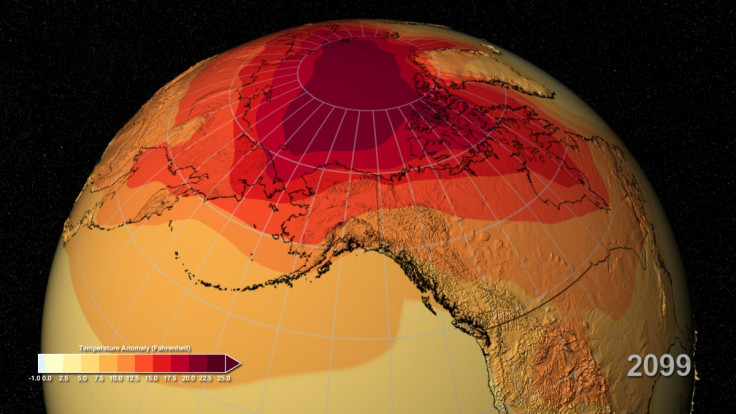

Crossing the 2-degree limit will invite catastrophic and irreversible impacts as predicted by climate scientists.

Led by Columbia University's Earth Institute Director Jeffrey Sachs, the Deep Decarbonization Pathway Project study looks at how to decarbonise the world's top economies and achieve worldwide carbon neutrality by the second half of this century.

"We have just about exhausted the carbon budget," Sachs told ClimateWire. "The world is unfortunately engaged in an unrecognized massive gamble with the future of the planet."

The report found that nations must develop and adopt low-carbon electricity, green the transportation and building sectors and raise energy efficiency.

In the United States, this will call for a total overhaul of the way energy is produced, delivered and used. The US is the world's second-largest emitter after China and uses more energy per person than any other nation.

The report, presented to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, is part of an effort among business leaders, economists and academics to build the technical and economic case for addressing climate change.

A global deal by parties to the global UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is expected to be signed in Paris in 2015. It is expected to include voluntary emission pledges by all big climate polluters.

The report called upon unwavering public support as governments usher in transformational changes, even as it found that serious de-carbonisation is possible even in countries like the Russian Federation. The world's fourth-largest emitter has not developed a de-carbonisation strategy.

A compromise

A major stumbling block has been the difficulty faced by nations in shifting gears from a market-oriented economy to an environment-regulated one. Despite reminders from scientists and international panels on the dangers of climate change ignored, there have hardly been any substantial change in the way governments have tried to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

That is what a perspective piece in the June issue of Nature Climate Change addresses. Lead author J Timmons Roberts, professor of Environmental Studies and Sociology, Brown University proposes a four-step compromise toward emissions reduction that offers "effectiveness, feasibility, and fairness."

The analysis, based on a carbon budget of 420 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide over the period 2012-50, suggests reducing the number of players in the reductions process and narrowing it down to 13 from 194 members. These 13 members of the Major Economies Forum are the largest emitters in the world and include both developed and developing nations, who together contribute 81.3% of total emissions.

They next propose a switch from production based to consumption based carbon accounting in order to factor in the final use of goods and services. Finally, they recommend a redistribution of burden, based on historical contributions and calculating economic responsibility of shares of carbon budget based on the economies of members.

The changes effected by the 13 members can be taken as the last step to the larger UN group through tools, methodologies, training and knowledge. Only if the MEF members agree to such a compromise can a meaningful outcome ever be achieved, the authors write.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.