How 3D printing is guiding US surgeons in full human face transplants

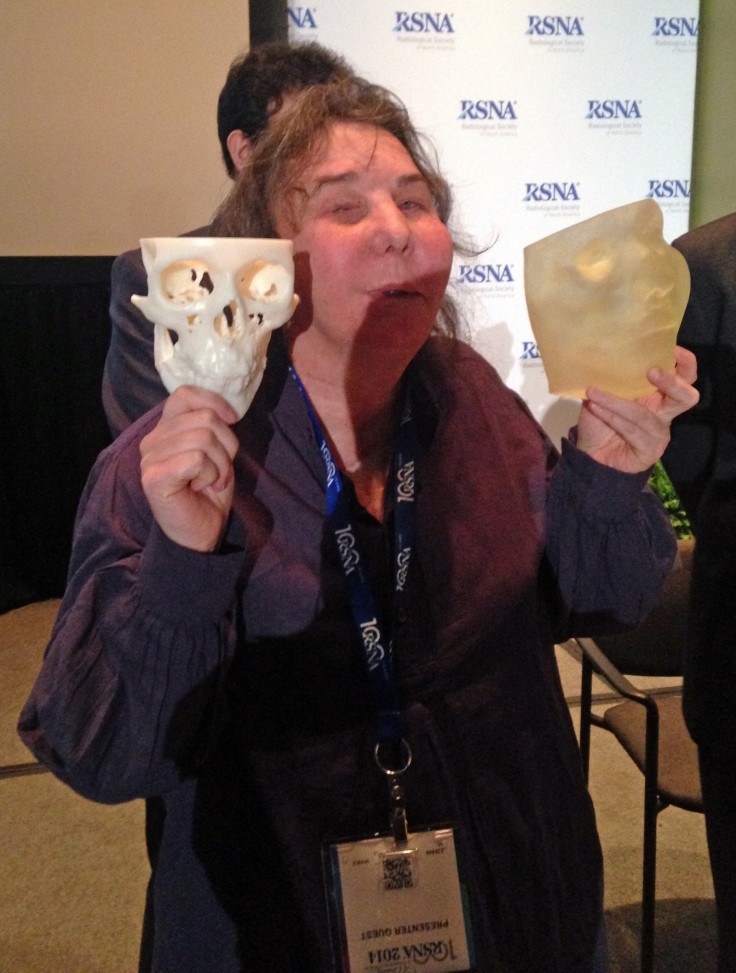

Surgeons at Brigham and Women's Hospital in the US are using 3D printed models of their patients' skin tissues and skulls to guide them in planning complex full facial transplants and presented their methods at the 2014 Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) annual meeting last week.

Full facial transplants have only existed since 2010 and are designed to help patients whose faces have been severely injured from horrific construction, electrical and shooting accidents, fires and maulings by dogs and bears.

To do this, surgeons have to remove what's left of a patient's face and replace it with a complete face from a donor, complete with lips, nose, tear ducts and eyelids.

This incredibly complex surgery can take up to 24 hours to complete and requires a full team of surgeons.

It also requires in-depth surgical planning to make sure the transplant is successful, and so Boston-based Brigham and Women's Hospital has begun using models 3D-printed using the Stratasys Objet500 Connex3 and Objet Eden 260VS 3D printers to support its efforts.

The hospital is the third in the world to have carried out full face transplants and was the first in the US.

"All seven patients who underwent full face transplants at Brigham and Women's Hospital have had boning models 3D-printed. It's only by having this bone model that we can understand the complex relationships of the bone and then plan the surgeries accordingly," said Dr Frank Rybicki, the director of Applied Imaging Science Laboratory at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

In order to make full face transplants possible, the doctors have to understand how the bones and the cardiovascular structure of muscles and tissue work together in the face, as these accidents affect not just soft tissues but also the structure of the skull.

On top of that, when patients come to these surgeons, they have already had emergency surgeries on their faces, perhaps to ensure that they can open their eyes and breathe properly, which makes the situation more complex as their skulls and tissue have become modified through the surgeries.

One example is Carmen Tarleton, a woman who was maimed by her husband and received a full-face transplant in 2013.

"Carmen had over 60 surgeries before she came to us, and that's why she had so much deformity, function deficit and a huge amount of pain from scar tissue every time she smiled or moved any of the muscles in her face," explained Rybicki.

In the past, surgeons have used CT scan data to create 3D visualisations of a patient's soft tissues and the bone underneath, but this is only a two-dimensional image that can be viewed on a computer screen.

By being able to 3D print out both the damaged facial tissue and the modified skull bone model beneath it, the doctors can get a visual representation of what has gone wrong.

This helps them to understand how to be able to give a patient a new face where the muscles and nerves are able to connect to the rest of the body to animate the face and provide sensation.

"What we found was that...we could take the skull model, put it with the soft tissue and have a really accurate 3D model of what Carmen would have looked like before the surgery," said Rybicki.

By continuing to create 3D models once the full face transplant was completed, the doctors have been able to track the changes over time as Tarleton's face continues to heal.

"There's really no other way we can track soft tissue changes over time and no other way we can appreciate these 3D [facial] volumes other than using 3D printing," Rybicki stressed.

"We're also going to start studying the science of what these tissue volumes mean, and it's very likely that this corresponds to other parts of full facial transplants, such as how the soft tissues remodel and whether the volume of tissue affects rejection [from the patient's body]."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.