Interstellar Object 3I/ATLAS: New Data Unveils 'Improbable' 120-Degree Symmetry

New findings reveal 'improbable' symmetry in the interstellar visitor

When the interstellar visitor 3I/ATLAS first flew into our cosmic neighborhood in July 2025, scientists all breathed a sigh of relief. It looked like we had found something we knew: an icy traveler that acted just like the comets we have been studying for hundreds of years. The Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) in Chile found the object on July 1, 2025. It was quickly identified as the third known interstellar visitor, following 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov.

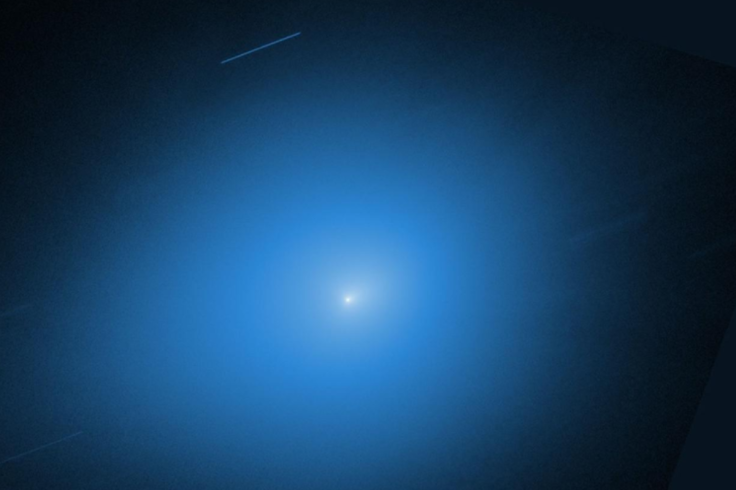

Early NASA images showed a simple scene of hydrogen gas slowly drifting away from a frozen nucleus. This process, called sublimation, fits perfectly with what we already know from our textbooks.

However, as the object made its closest approach to the sun on Oct. 29, 2025, that comfortable narrative began to unravel. What was once a cautious institutional snapshot, released in the wake of a disruptive 43-day government shutdown that lasted from Oct. 1 to mid-November, now lags significantly behind a wave of startling new evidence. Far from being a simple ball of ice, 3I/ATLAS is proving to be one of the most complex and enigmatic objects ever to traverse our solar system.

Why 3I/ATLAS Defies Early Models

The original NASA graphics relied on a 'diffuse model,' where hydrogen was treated as a secondary byproduct drifting outward in a random, cloud-like halo. Recent high-resolution reprocessing of data from the Hubble Space Telescope has shattered this assumption.

Instead of a random mist, researchers have identified organised jet systems that rotate in perfect coherence with the object's spin. These observations, bolstered by data from the James Webb Space Telescope and the MAVEN spacecraft at Mars, suggest the object is far more dynamic than initially reported.

Most striking is the geometric precision of these features. Observers have found three distinct inner jets spaced at nearly perfect 120-degree intervals. Such a level of symmetry is statistically improbable for a natural, irregular icy body and has led experts like Harvard's Avi Loeb to describe the configuration as 'hard to explain' via standard cometary physics. This 'structured motion' suggests that the hydrogen detected earlier is not freely dispersing into the void, but is instead physically linked to these powerful, discrete engines of gas.

Furthermore, the velocity scales used in early models — topping out at 120 kilometres per second — are no longer sufficient. Newer modelling indicates that the hydrogen is being influenced by non-thermal processes, including radiation pressure and jet collimation. Some material remains stubbornly slow and structured, while other components accelerate in ways that simple thermal escape cannot explain. In short, 3I/ATLAS is not just 'off-gassing'; it is behaving like a finely tuned machine.

Hidden Depths: Probing the Nucleus of 3I/ATLAS

Perhaps the greatest limitation of early reports was the 'unresolved' nature of the inner coma. At the time of discovery, the region within 10,000 to 30,000 kilometres of the nucleus was a blurry mystery. We now know this is the 'engine room' where the object's true physical behaviour diverges from every standard cometary model. High-resolution imaging from the HiRISE camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) has recently provided spatial resolution as fine as 30 kilometres per pixel, offering the clearest view yet of this inner sanctum.

Current estimates for the nucleus size remain broad, ranging from 440 metres to 5.6 kilometres in diameter. However, the sheer volume of sustained activity observed as the comet passed Mars on Oct. 3, 2025 at a distance of just 29 million kilometres suggests the object is either much larger than first believed or possesses an internal structure capable of transporting energy in highly unconventional ways. Loeb has even suggested the object could be at least a thousand times more massive than its predecessors, 1I/'Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov.

The role of hydrogen as a primary diagnostic tool has also been demoted. Later observations have revealed a thick shroud of fine dust grains — roughly ten microns in size — forming a coma that borders on opaque. This dust partially shields the nucleus from sunlight, yet the object's activity remains undiminished. This implies that 3I/ATLAS may be drawing on internal energy reserves or is far more robust than the 'dirty snowball' model suggests.

As 3I/ATLAS begins its long journey back into the interstellar dark, passing the orbit of Jupiter in spring 2026, it leaves behind a strained set of scientific theories. Having made its closest flyby of Earth on Dec. 19, 2025 at a distance of 270 million kilometres, the visitor remains observable via ground-based telescopes until it finally exits our neighborhood.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.