Mummies discovered in Hungarian crypt reveal how tuberculosis ravaged Europe

Mummified bodies discovered in a Hungarian crypt have revealed how tuberculosis ravaged 18<sup>th century Europe, with multiple strains infecting people across the region.

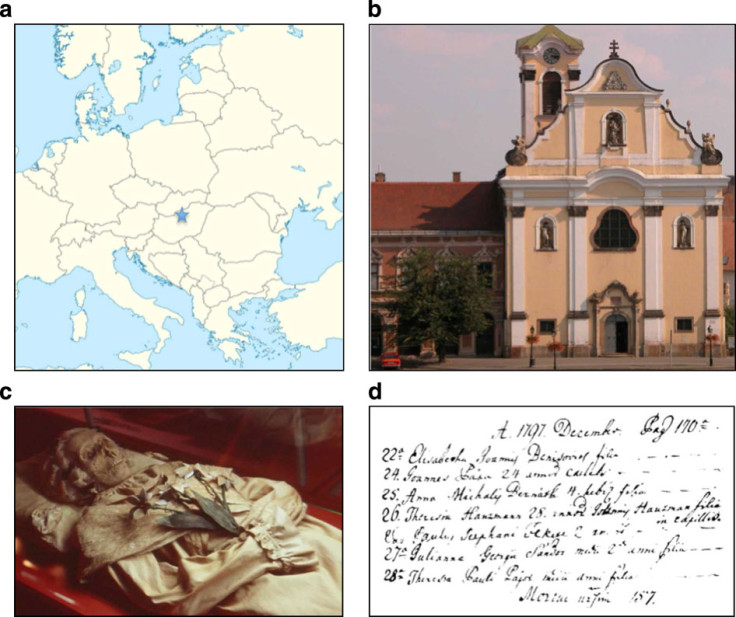

The 200-year-old crypt in the Dominican church of Vác in Hungary provided scientists with 14 TB genomes, suggesting mixed infections were common when the disease peaked in Europe.

Publishing their findings in Nature Communications, researchers at the University of Warwick dubbed the find as "significant" as it could provide clues about future infection control and diagnosis.

Along with the multiple strains, researchers found evidence of a link between strains between a middle-aged mother and her daughter, suggesting both died from the infection.

The team identified the TB DNA through a technique called metagenomics, which involves direct sequencing of DNA without growing bacteria or deliberately picking out the TB DNA.

They used 18<sup>th century sequences to date the origin of the lineage of TB strains found in Europe and America to the late Roman period – fitting with the suggestion that the most recent common ancestor of TB emerged 6,000 years ago.

Lead author Mark Pallen said: "Microbiological analyses of samples from contemporary TB patients usually report a single strain of tuberculosis per patient. By contrast, five of the eight bodies in our study yielded more than one type of tuberculosis – remarkably from one individual we obtained evidence of three distinct strains.

"By showing that historical strains can be accurately mapped to contemporary lineages, we have ruled out, for early modern Europe, the kind of scenario recently proposed for the Americas—that is wholesale replacement of one major lineage by another—and have confirmed the genotypic continuity of an infection that has ravaged the heart of Europe since prehistoric times."

He said that with a current resurge of TB in many parts of the world, their findings can be used to characterise pathogens in contemporary samples: "Such approaches might soon also inform current and future infectious disease diagnosis and control."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.