NASA prepares space travellers to explore new worlds

Fungi are growing in closed habitats, endangering human health.

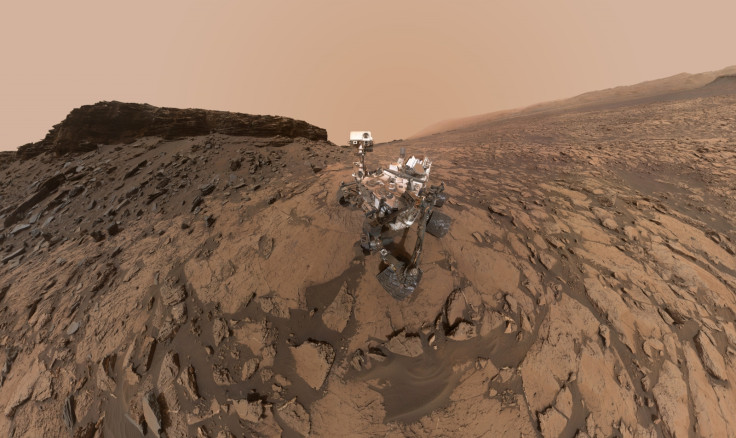

Planning future space explorations, including long missions to Mars, will require building safe closed habitats to ensure that space travellers are kept safe in new worlds far away from Earth.

The threat of contracting painful infections and allergies is multiplied in these isolated environments which can change the composition of the fungal community, that include yeasts and molds, but also the more familiar mushrooms. They are present on the surface of these habitats and this can be problematic because some are pathogenic.

They can colonise the human body and cause allergies, asthma and even skin infections. Understanding how they grow when humans live in closed space habitats is vital to safeguard their health during space journeys.

In a study published in the journal Microbiome, Nasa scientists simulated one of these safe closed space habitats.

"Our study is the first report on the microbiome of a simulated habitat meant for the future human habitation of other planets. We used the Inflatable Lunar/Mars Analog Habitat (ILMAH), a unique, simulated closed environment that mimics the conditions found on the International Space Station and possible human habitats on other planets," study author Dr Kasthuri Venkateswaran, Senior Research Scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory said. "We showed that the overall fungal diversity changed when humans were present."

Cleaning up the space habitat

The ILMAH was primarily commissioned to measure physiological, psychological, and immunological characteristics of human living in isolation. However, it was also an opportunity to examine the microbiological aspects.

They recruited three student crews which were housed inside the ILMAH for 30 days. The habitat was completely isolated from the outside world, except for an exchange of filtered air between the indoor and outdoor environments. The participants were given tasks to do, including cleaning up the habitat and collecting surface samples throughout their stay - at 3, 20 and 30 days of habitation.

These samples were then analysed and characterised by the scientists. They found that the composition of the fungal community in the habitat had changed over time. Certain kinds of fungi - including known pathogens that can cause allergies, asthma and skin infections in humans - increased in number while the students were living inside the ILMAH.

Meanwhile, prolonged stays in closed habitats could also be stressful for inhabitants and might weaken their immune system, making them more vulnerable to the pathogens.

"Fungi are extremophiles that can survive harsh conditions and environments like deserts, caves or nuclear accident sites, and they are known to be difficult to eradicate from other environments including indoor and closed spaces," Venkateswaran explained.

"Characterising and understanding possible changes to, and survival of, fungal species in environments like the ILMAH is of high importance since fungi are not only potentially hazardous to the inhabitants but could also deteriorate the habitats themselves."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.