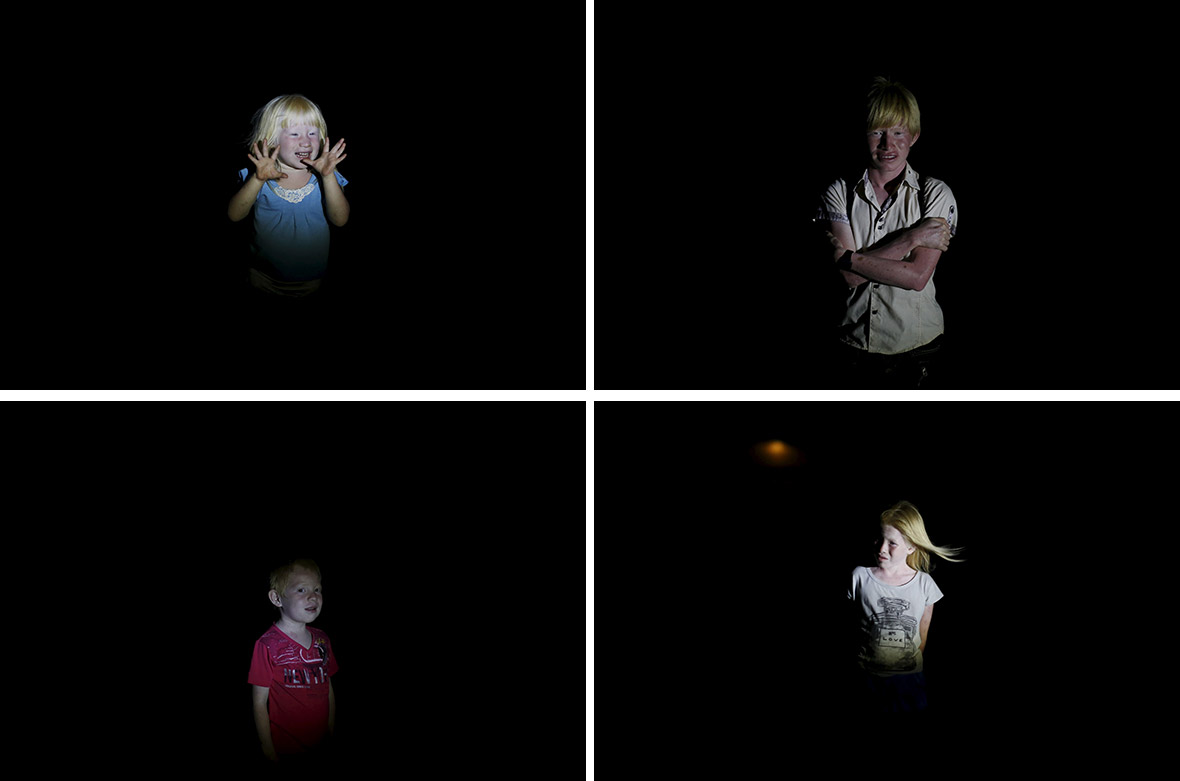

Panama: The islands home to hundreds of albinos who must hide from the tropical sun [Photos]

There are hundreds of people with albinism among the 80,000 indigenous Guna who live on islands off the Caribbean coast of Panama. One in every 150 Guna children born is albino, according to Pascale Jeambrun, founder of the local SOS Albino organisation. At a global level, the rate is around one in 20,000.

For years, the alabaster-skinned people born on this sun-scorched constellation of islands off the Caribbean coast of Panama have been venerated as the the Children of the Moon or the Grandchildren of the Sun. But that same sun is also their greatest foe.

More than half of the region's albinos suffer some form of skin cancer, said Jose Jons, a doctor on the island of Ustupu, compared with an incidence of less than 1% in the global population, according to World Health Organization figures.

As modern medical knowledge about the illness has begun to penetrate the region's atolls, reported cases of skin cancers have risen, said Rosa Espana, head of dermatology at the National Oncology Institute in Panama City. She now sees about three Guna albinos a week in her clinic.

"Until there's a good cancer prevention campaign focused on the Guna, or a dermatology centre there, the problem is going to keep getting worse for the Guna albinos," Espana said.

Because of their sensitive skin, young Guna albinos must be shuttled to and from school, avoiding the baking heat, while they watch their friends play in the streets. The pale eyes of the Guna albinos are also vulnerable to nystagmus, an involuntary eye movement which can impair vision.

According to local legend, the first albino sent to the Guna people by their God, Baba or Bab Dummat, was known as Mago, and considered the father of the sun, Ferrer said. Those who came after Mago are now known as the Children of the Moon, or the Grandchildren of the Sun.

Samuel Jimenez, a 57-year-old albino leader on the island of Archutupu, remembers that as a child, his grandmother would make him stay up late during an eclipse to ward off a mythical winged animal the Guna believe would try and gobble up the moon. "That's why we carry a bow and arrow," he said. "To shoot the beast."

In some countries, such as Tanzania, albinos can be persecuted and killed as a symbol of bad luck, or witchcraft. But the Guna treat their albino children with love and respect.

"As the ancestors say, it's a blessing," said Yira Boyd, mother of six-year-old Guna albino girl Delyane Avila. "If you look after them you can arrive at that special place in the heavens."

People with albinism were not always treated well by their fellow Guna. After Spain colonised the region, until the end of the 19th century, the Guna slaughtered their albinos in the misguided belief they were related to their European overlords, said local albino spiritual leader Maximiliano Ferrer.

From the start of the 20th century, a spiritual reformation blossomed among the Guna, who rediscovered their traditional beliefs and a love of their albino offspring.

The United Nations has established 13 June as International Albinism Awareness Day. Every year thousands of people around the world are born with oculocutaneous albinism, caused by a lack of the pigment melanin, which gives hair, skin and eyes their colour.

The majority of cases of albinism are passed on in an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, which means you need to inherit two copies of the faulty gene – one from the mother and one from the father – to have the condition.

Carriers of the gene have a normal amount of melanin and are not affected by albinism. According to the NHS, there is a one in four chance that the child of parents who both carry the gene will have albinism.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.