Pet Imaging Can Predict Whether Brain-Damaged Patients Will Wake Again

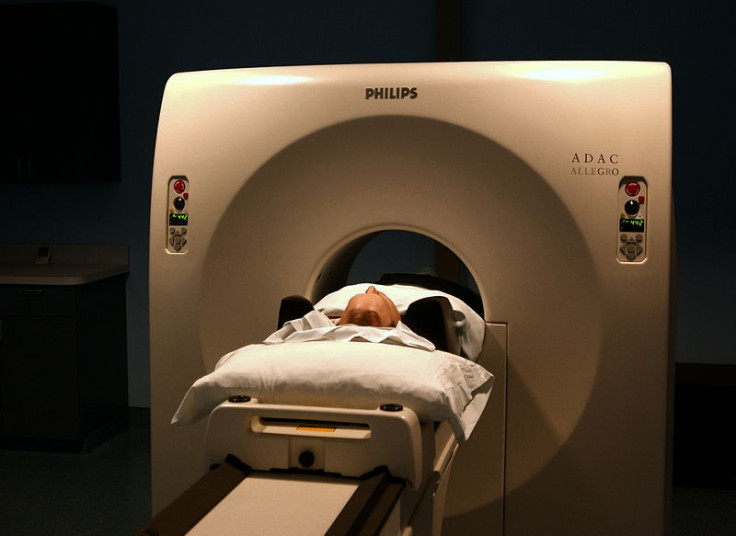

Researchers studying brain scanning techniques have found that positron emission tomography (Pet) is able to accurately predict whether a brain-damaged patient in a vegetative state will regain consciousness.

Bedside clinical examinations have traditionally used to determine what state of unconsciousness a patient is in, but up to 40% of patients are misdiagnosed.

The examinations are used to determine whether a patient is in a minimally conscious state (MCS), where there is some evidence that the patient is aware and responds to a stimuli, or if the patient is in a vegetative state (VS), whereby they are awake but completely unresponsive.

"In patients with substantial cerebral oedema [swelling of the brain], prediction of outcome on the basis of standard clinical examination and structural brain imaging is probably little better than flipping a coin," writes Jamie Sleigh of the University of Auckland and Catherine Warnaby of the University of Oxford in response to the study.

Vegetative state or conscious?

The researchers at the University of Liège, University of Western Ontario and the University of Copenhagen looked at whether Pet using the imaging agent fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) or functional MRI (fMRI) could distinguish between the vegetative and MCS states in 126 patients with severe brain injury.

Their research paper, "Diagnostic precision of PET imaging and functional MRI in disorders of consciousness: a clinical validation study" is published in the Lancet.

Out of the patients, 81 were in an MCS state, 41 were in a vegetative state, and a control group of four patients suffered from locked-in syndrome, whereby they were conscious but behaviourally unresponsive.

All the patients had been referred to the University Hospital of Liége, in Belgium, from across Europe.

"Our findings suggest that Pet imaging can reveal cognitive processes that aren't visible through traditional bedside tests, and could substantially complement standard behavioural assessments to identify unresponsive or 'vegetative' patients who have the potential for long-term recovery," said study leader Prof Steven Laureys.

Overall, FDG-Pet brain imaging was better than fMRI in establishing which patients were conscious. FDG-Pet was 74% accurate in predicting the extent of how much a patient would recover within 12 months.

"From these data, it would be hard to sustain a confident diagnosis of unresponsive wakefulness syndrome solely on behavioural grounds, without Pet imaging for confirmation. [This] work serves as a signpost for future studies," said Sleigh and Warnaby.

"Functional brain imaging is expensive and technically challenging, but it will almost certainly become cheaper and easier. In the future, we will probably look back in amazement at how we were ever able to practise without it."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.