Prehistoric dentists: Neanderthals used toothpicks 130,000 years ago

The Neanderthal individual appeared to have experienced irritation and discomfort.

The remains of toothpick grooves on Neanderthal teeth suggest that archaic humans were trying to treat their dental problems as far back as 130,000 years ago. For scientists, this is evidence of a kind of prehistoric dentistry.

Many studies have found toothpick grooves in the fossilised teeth of ancient humans, some as old as two million years, but this behaviour had not often been associated with Neanderthals.

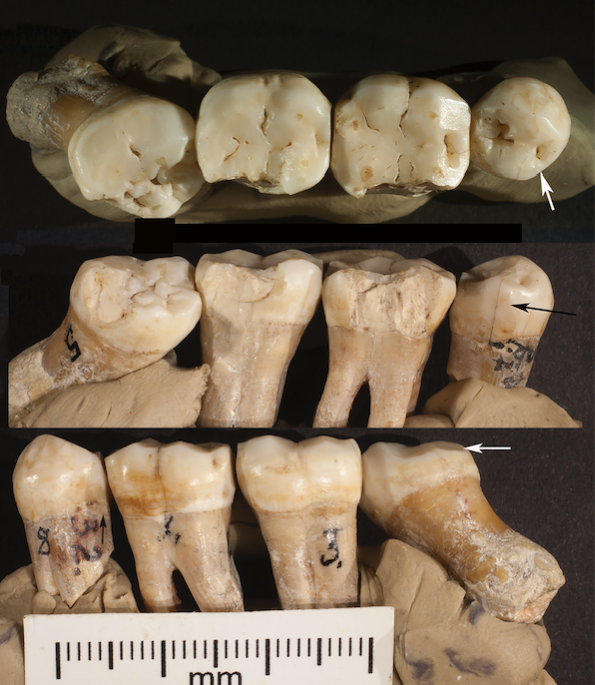

The findings, described in the Bulletin of the International Association for Paleodontology, were made after the researchers analysed four mandibular teeth on the left side of the mouth of a Neanderthal individual.

These teeth are not a new find – they had been discovered more than a century ago at the site of Krapina in Croatia.

However, researchers are currently in the process of re-examining artefacts and human remains that were recovered during the excavation of the site, which took place between 1899 and 1905.

They recently published a study describing one such artefact– jewellery made out of eagle claws.

In this research, the teeth were analysed in detail using a light microscope to document occlusal wear, toothpick groove formation, scratches, and enamel fractures that occurred before the individual's death.

Self-medicating against dental irritation

The researchers identified scratches and grooves on the teeth that suggest that they were likely causing irritation and discomfort to the Neanderthal man or woman they belonged to. However, in the absence of the mandible, the scientists are unable to say whether he or she would have suffered from a severe dental issue such as periodontal disease.

What appears certain however is that the individual attempted to 'self-medicate' to alleviate the dental irritation.

Two of the teeth were indeed pushed out of their normal positions. Associated with that, six toothpick grooves were recovered from among those two teeth and from the two molars further behind them. The results of the analyses rule out that the breaks in the teeth were done after the individual's death and rather suggest manipulations to alleviate dental problems.

"As a package, this fits together as a dental problem that the Neanderthal was having and was trying to presumably treat itself, with the toothpick grooves, the breaks and also with the scratches on the premolar," said study lead author David Frayer, professor emeritus of Anthropology at the University of Kansas.

"It was an interesting connection or collection of phenomena that fit together in a way that we would expect a modern human to do. Everybody has had dental pain, and they know what it's like to have a problem with an impacted tooth."

The scientists said that combined with the discovery of the eagle claw jewellery, these toothpick marks and dental manipulations are interesting because they challenge the idea that Neanderthals were subhumans, with much less advanced skills than modern humans.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.