Space: Sea of Orphaned Stars Producing Cosmic Glow, Says Study

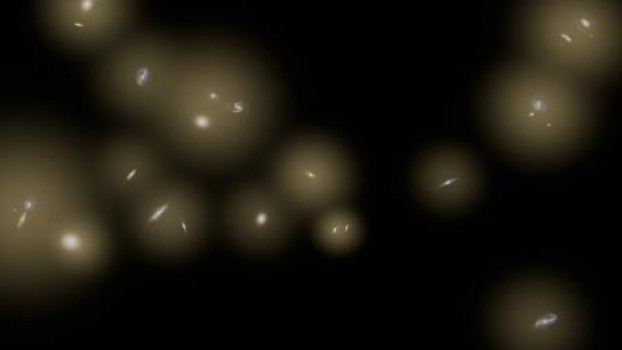

Orphaned stars ripped from galaxies and thrown out during collisions and mergers in space could explain the diffuse cosmic glow, say Caltech researchers.

Data obtained from a Nasa suborbital rocket suggests that many such stars permeate the dark space between galaxies and form an interconnected sea of stars throwing out the light.

The findings by Caltech Professor of Physics Jamie Bock and Caltech Senior Postdoctoral Fellow Michael Zemcov have been published in the journal Science.

Galaxies form in dark matter dense regions formed in the early expanding universe. They tend to cluster together as well. Scientists were looking to measure the large-scale structure directly from maps looking at longer infrared radiation produced by the Herschel observatory.

Meanwhile, another group was looking at the extragalactic infrared background that represents all of the infrared light from all of the sources in the universe, and intrigued that not all of it could be traced back to a source.

When calculating the light produced by individual galaxies, it added up to less than the background light seen.

Measuring the total sky brightness directly was a challenge due to the foreground "Zodiacal light", or dust in the solar system reflecting light from the sun.

The best way they decided to get at the extragalactic background was to measure spatial fluctuations on angular scales around a degree.

Cosmic experiment

That led to the Cosmic Infrared Background Experiment (CIBER) project that saw a probe spend just enough time above the atmosphere to click the pictures and gather starlight.

With its camera and two spectrometers to determine the brightness of zodiacal light and measure the cosmic infrared background directly, fluctuations in two wavelengths of near infrared light were measured.

After removing the fluctuations arising from solar system, known galaxies and stars, they filtered out the remaining background light. Comparisons were done with the Spitzer data for the same period.

The end result was a very bright, blue wavelength of light.

It was too bright to be from the early galaxies as it demanded huge quantities of hydrogen burnt as also synthesis of heavy elements, both of which were absent.

"The colour is also too blue," said Caltech Senior Postdoctoral Fellow Michael Zemcov. "First galaxies should appear redder due to their light being absorbed by hydrogen, and we do not see any evidence for such an absorption feature."

The best interpretation was that the light came from stars outside of galaxies but in the same dark matter halos. In short, the orphaned stars.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.