3I/ATLAS Shock: Interstellar Object 'Bleeding Matter' In Way No Comet Should

3I/ATLAS defies comet behaviour: steady dust 'bleeding', anti-tail anomalies and Jupiter fly-by ahead

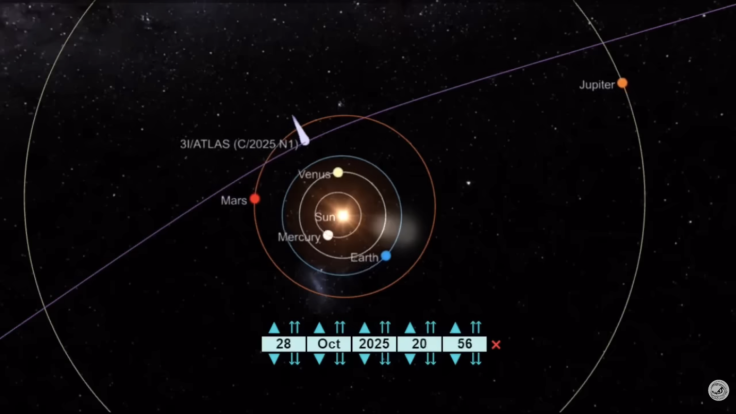

Discovered on July 1, 2025 by the ATLAS survey telescope in Chile, 3I/ATLAS — the third confirmed interstellar object after 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov — hurtled into our solar system at an inbound velocity of about 44 km/s. This rare visitor, designated C/2025 N1 (ATLAS), reached perihelion on Oct. 29 or 30, 2025 at roughly 130 million miles (210 million km) from the sun, inside Mars' orbit, travelling at around 152,000 mph (245,000 km/h). Now post-perihelion, it is racing outbound on a retrograde trajectory inclined at about 5° to the ecliptic, setting up a close approach to Jupiter at 0.357 AU (about 33 million miles or 53 million km) in March 2026 — remarkably near the gas giant's Hill sphere boundary.

The interstellar visitor known as 3I/ATLAS is quietly tearing itself apart — but in a way that no ordinary comet should. Instead of the chaotic outbursts astronomers expect when ice and dust meet the heat of a star, this object appears to be bleeding material with eerie steadiness, as if governed by rules that standard comet theory never anticipated.

Recent NASA observations, including from Parker Solar Probe's WISPR instrument between Oct. 18 and Nov. 5, 2025, and detections of hydroxyl gas (a water fingerprint) via the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, confirm ongoing activity dominated initially by dust, with CO2 gas and H2O ice noted in the coma — though water gas remains low.

3I/ATLAS Mass Loss Defies Comet Textbook

Fresh observations from Tenerife, Spain, captured with the Transient Survey Telescope and the Two-Meter Twin Telescope, show that 3I/ATLAS is not merely shedding dust, but doing so with remarkable precision and internal consistency. The images reveal an interstellar body whose behaviour looks more like a controlled leak than a natural, unstable object rushing past the sun. Pre-perihelion images also revealed a giant sunward jet of gas and dust, alongside green cyanogen emission and an extended anti-tail from mm-scale grains drifting under radiation pressure — features that transitioned from a condensed coma earlier in its approach.

On paper, the figures hardly look sensational: around ten million kilograms of dust released over roughly a month, with a dust production rate near three kilograms per second. Gas still dominates the mass loss, there are no explosive flares, no catastrophic breakups — yet that calm profile is precisely what makes the data so unsettling for comet science.

Ordinary comets, especially near perihelion, lose mass in fits and starts: activity spikes, collapses, stutters and flares as sunlight reaches volatile pockets and fractures the surface. In contrast, the Tenerife data point to a controlled, sustained release, more like a slow haemorrhage than a violent rupture, and that distinction hints at an underlying mechanism that current models simply do not describe. Notably, the object showed no major anomalies at perihelion, with rapid brightening confirmed through solar conjunction via space-based imagers like NOAA GOES-19 CCOR-1 and SOHO LASCO.

3I/ATLAS Dust Trail Hints at Hidden Order

Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb's calculations suggest that the strange 'anti-tail' seen in 3I/ATLAS cannot be explained by the ultra-fine dust grains typically found in cometary comae, which would be swept away almost instantly by sunlight. Nor can the observed jet be made of larger grains or pebbles, since gas drag would struggle to accelerate those to the measured speeds. The numbers force an awkward compromise: dust grains roughly ten microns across, present in extraordinary quantities.

Here the story of mass loss becomes far more intriguing. To produce the observed brightness, the glow around 3I/ATLAS behaves as though sunlight were reflecting off a single mirror with a radius of about ten kilometres, which sounds poetic but encodes a stark physical reality. Because brightness scales with surface area, and surface area with the square of size, matching that glow demands on the order of 10 separate dust particles — each tiny, but together forming a massive, organised outflow.

Crucially, those grains must be replenished continuously and at almost the same rate over weeks. If the supply faltered, the anti-tail would contract; if it surged, the structure would smear out or fragment. Instead, over observation windows separated by weeks and millions of kilometres of travel, the geometry stays strikingly stable, implying a system that is regulated rather than random.

The estimated dust mass-loss rate, at about 0.7% of the total gas loss, echoes the dust-to-gas ratio of the Milky Way's interstellar medium, but with an important twist. In typical interstellar space, most dust grains are smaller than one micron, while ten-micron particles are rare outside dense molecular clouds where dust can grow, stick and settle.

If 3I/ATLAS is preferentially shedding ten-micron dust, it hints not only at an origin in such an environment, but also at a surface that is layered and cohesive, able to release particles within a narrow size band without triggering a cascading failure. Precovery observations from TESS in May-June 2025 suggest it was already active at 6.4 AU, with a nucleus size upper limit of radius less than 2.8 km from Hubble data, making it larger than prior interstellar objects.

3I/ATLAS Data Gaps Fuel Transparency Questions

A forensic review of Laplacian-filtered Tenerife images reinforces the picture of order rather than chaos: the anti-tail is not diffuse but collimated, with an axis that does not wander randomly or fan out under solar radiation pressure as a loose plume should.

The brightness peak remains sharply defined, and the jet's orientation shifts smoothly with changing viewing geometry — pattern evidence, in legal terms, pointing to a repeatable, constrained internal mechanism. Loeb has speculated on non-gravitational accelerations from mass-loss jets steering it precisely toward Jupiter's Hill radius, a rare alignment, though standard cometary models suffice for many.

Equally striking is what is missing. There are no signs of rotational shedding, no chaotic torque-driven breakup, no episodic venting of the kind associated with volatile-rich nuclei. The object is losing mass, but it appears to do so conservatively, as though preserving structural integrity were a priority rather than a coincidence.

This leads directly to an uncomfortable transparency issue. Ground-based observatories have released detailed data products, yet higher-resolution views from space-based instruments — capable of tracing fine dust dynamics, compositional gradients and near-nucleus behaviour — remain conspicuously limited in the public domain.

Those are precisely the data needed to test whether this mass-loss regime is genuinely unprecedented, and their absence invites scrutiny, even as speculation remains unwarranted. As 3I/ATLAS fades outbound, passing 167 million miles from Earth on Dec. 19, 2025 with no Earth threat, missions like ESA's Comet Interceptor (launch 2029) aim to chase future interstellar visitors.

No one is claiming that 3I/ATLAS is artificial. But the evidence increasingly indicates that it is not behaving like any comet previously modelled, shedding matter slowly and selectively with a consistency that challenges long-held assumptions about how interstellar bodies weather, erode and survive their journeys between the stars.

As 3I/ATLAS speeds towards its intriguing rendezvous with Jupiter in March 2026, its orderly 'bleeding' of dust raises profound questions about the true nature of interstellar wanderers — stay tuned for updates and join the global astronomy community in tracking this cosmic enigma via platforms like the International Astronomical Union's Minor Planet Center.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.