Amber Rudd doesn't understand how strong encryption works, pledges to break it anyway

The state vs encryption: Debate rages about balance between security and privacy.

UK home secretary Amber Rudd has admitted that she doesn't fully understand the technology behind strong encryption, but still wants to break down its security anyway.

"I don't need to understand how encryption works to understand how it's helping the criminals," Rudd said during a fringe event at the Conservative party conference this week (2 October). "I will engage with the security services to find the best way to combat that."

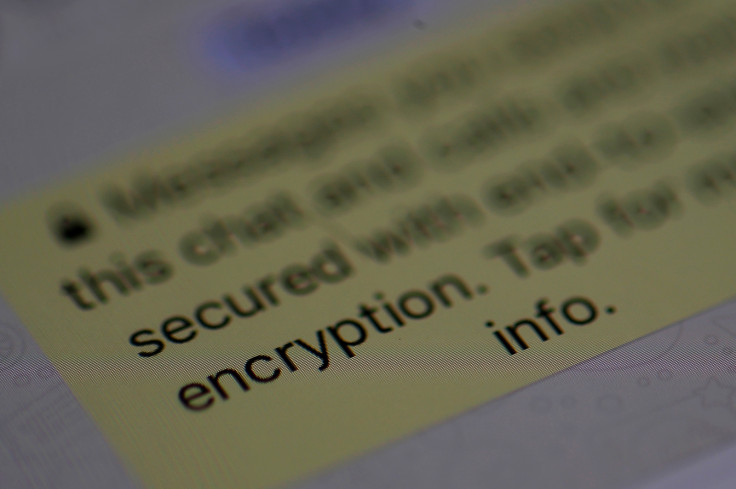

Major technology companies like WhatsApp, Apple and Microsoft each use end-to-end encryption in chat, messaging and corporate applications.

The mathematical protocol means that the content of communications is scrambled, which in turn helps to protect it against snooping and interception.

On one hand, security services across the world claim that popular applications provide "safe spaces" for terrorists and criminals to plot nefarious schemes.

On the other, security experts and digital rights campaigners stress that cryptography is used in everything from internet banking to online shopping.

Breaking down its fundamental security will leave everyone worse off, they argue.

During the conference this week, Rudd was questioned by Michael Beckerman, chief executive of the Internet Association, who said that encryption is mathematical and it "can't be uninvented".

"I am not suggesting you give us the code," the home secretary responded. "I understand the principle of end-to-end encryption – it can't be unwrapped. That's what has been developed.

"What I am saying is the companies who are developing that should work with us."

Rudd went on to slam the technology firms for a "patronising stance" in response to potential government regulation and (yet again) said they need to do more to help stop terrorism.

"It's so easy to be patronised in this business. We will do our best to understand it," she said, as first reported by the BBC.

"We will take advice from other people but I do feel that there is a sea of criticism for any of us who try and legislate in new areas, who will automatically be sneered at and laughed at for not getting it right." The official government stance is that it doesn't want 'back door' access.

But it can't have it both ways, experts warn.

"Rudd has highlighted her own shortcomings in understanding the basic workings of encryption," commented Kevin Bocek, chief strategist at cybersecurity firm Venafi.

"Encrypted messaging apps are just the tip of the iceberg," he said. "What Rudd fails to understand is that encryption is fundamental to the success of the UK economy.

"The reality of end-to-end encryption means tech companies are unable to give access – it is not simply theory but the laws of mathematics.

"Breaking encryption [is] impossible without a backdoor, which leaves systems accessible to cybercriminals alongside law enforcement.

"Rudd is proposing to make the public safer from terrorists – with no proof that removing encryption will have an impact – while leaving them at the mercy of cybercriminals."

Encrypted chat apps became increasingly popular following the Edward Snowden revelations in 2013.

His leaks, taken from the US National Security Agency (NSA) revealed how British intelligence was retaining the text and phonecall metadata of the entire population in bulk.

This broad process, which was for years orchestrated without any parliamentary oversight, included the communications of citizens not suspected of committing crimes.

WhatsApp, for its part, provides UK authorities with metadata – information that experts say is more valuable to the security services than the content of communications. Metadata reveals who is sending the messages, what times messages were sent and users' email addresses.

In 2016, the UK government passed the Investigatory Powers Bill (IPBill), which gave political backing to some of the more controversial aspects of the Snowden revelations.

It gave police and the security services unprecedented access to communications via remote hacking and demanded telecommunication firms store them for up to 12 months.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.