Ancient long lost Greek sunken city was actually built by microbes five million years ago

What were thought to be the remains of an ancient, long-lost Greek city submerged off the coast of Zakynthos have turned out to be the result of natural processes. The site, which was discovered by divers several years ago, was actually constructed by microbes thanks to a natural phenomenon that took place five million years ago.

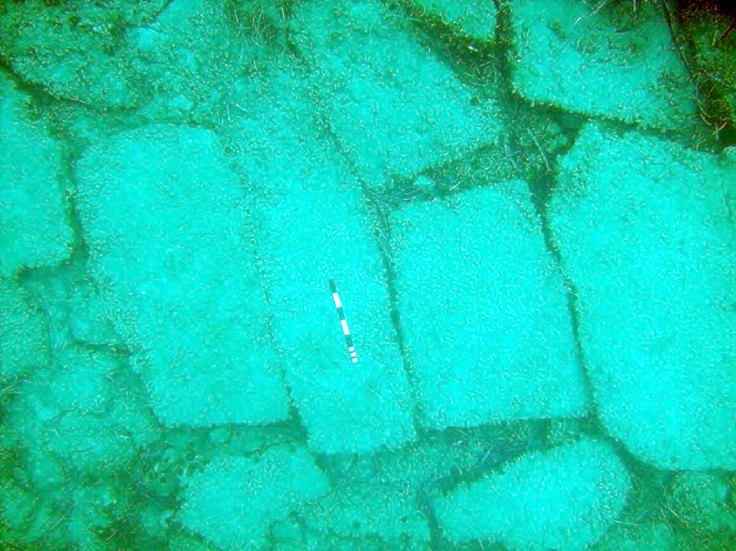

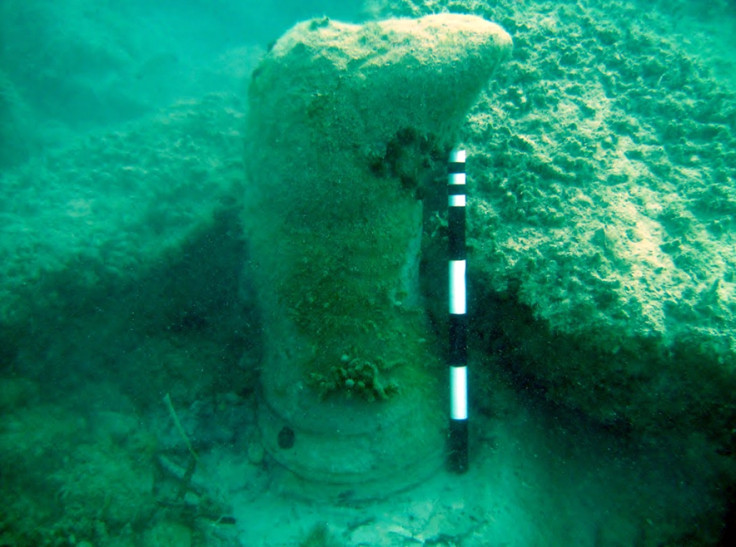

Divers had found what appears to be paved floors, courtyards and column bases. However, no other evidence of antiquities exist at this site. Instead, scientists from the University of East Anglia and the University of Athens considered the possibility of geological origin.

Lead author Prof Julian Andrews said: "The site was discovered by snorkellers and first thought to be an ancient city port, lost to the sea. There were what superficially looked like circular column bases, and paved floors. But mysteriously no other signs of life – such as pottery.

"The disk and doughnut morphology, which looked a bit like circular column bases, is typical of mineralization at hydrocarbon seeps – seen both in modern seafloor and palaeo settings."

Researchers analysed the mineral content and texture of the formations in extreme detail, using X-ray, microscopy and stable isotope techniques. "We investigated the site, which is between two and five meters under water, and found that it is actually a natural geologically occurring phenomenon," Andrews said.

"We found that the linear distribution of these doughnut shaped concretions is likely the result of a sub-surface fault which has not fully ruptured the surface of the sea bed. The fault allowed gases, particularly methane, to escape from depth."

He said microbes in the sediment used carbon in the methane as fuel. This then led to chemical changes that caused a natural cement to form. "In this case the cement was an unusual mineral called dolomite which rarely forms in seawater, but can be quite common in microbe-rich sediments. These concretions were then exhumed by erosion to be exposed on the seabed today.

"This kind of phenomenon is quite rare in shallow waters. Most similar discoveries tend to be many hundreds and often thousands of meters deep underwater. These features are proof of natural methane seeping out of rock from hydrocarbon reservoirs."

The study of the formations, published in Marine and Petroleum Geology, concludes: "Exhumed sediment-hosted concretions exposed in shallow marine settings can be readily confused with archaeological artefacts in countries like Greece which are rich in submerged antiquities, but the extent of which are still poorly known.

"We summarise our findings with the maxim 'all that glistens is not gold' or in this case 'columns and pavements in the sea, not always antiquities will be'."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.