Autoimmune disease: T-cell engineering targets problem cells without weakening immunity

Therapy for autoimmune diseases shows promising results in tests on mice.

A new therapy to treat autoimmune disorders without weakening the immune system has shown promising results in animal trials, scientists have announced. The technique is based on an anti-cancer strategy which involves the re-engineering of immune T-cells to destroy malignant tumour cells.

There are more than eighty types of autoimmune diseases – debilitating disorders in which some immune cells attack and destroy healthy body tissues by mistake. A number of treatments exists, but most end up suppressing a large part of the immune system, thereby leaving people vulnerable to all kinds of diseases.

This study, published in Science, focused on a specific kind of autoimmune disease known as pemphigus vulgaris (PV).

People who suffer from it see some of their antibodies - known as anti-Dsg3 antibodies - attack a protein called desmoglein-3 (Dsg3) that keep skin cells together. This results in severe blistering and leaves people more prone to infections.

The researchers wanted to show that a T-cell engineering approach used against cancer could help PV patients without harming their entire immune system.

If successful, the approach could also be used down the line to treat other autoimmune diseases.

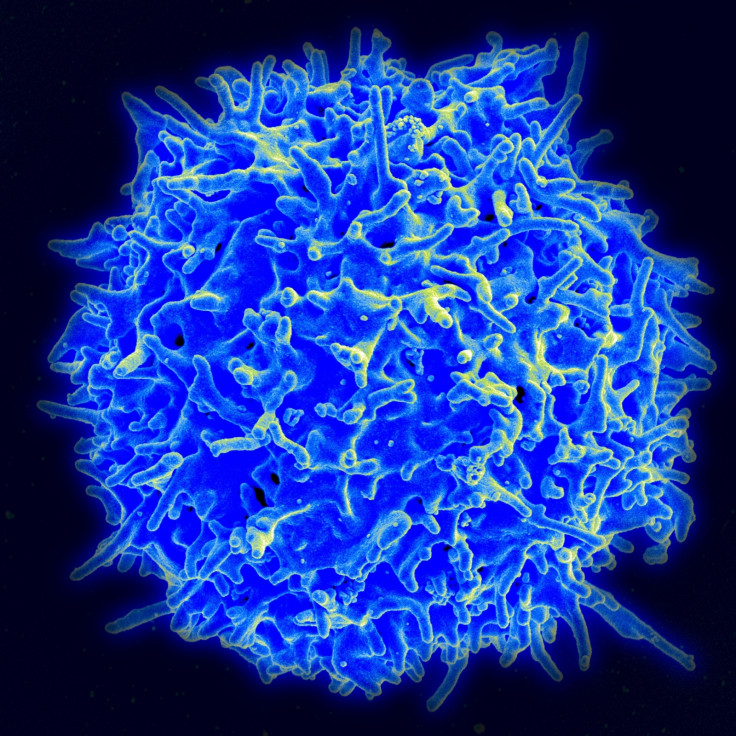

T-cells engineering

T-cell engineering is the process by which cancer patients immune T-cells are re-engineered by scientists so that they express a new receptor on their surface – one that targets cancerous cells and kills them off.

In this study, the scientists from the University of Pennsylvania decided to re-engineer PV patients' T cells so that they would target the immune B-cells that produce harmful anti-Dsg3 antibodies.

"We thought we could adapt this technology that's really good at killing all B cells in the body to target specifically the B cells that make antibodies that cause PV," explains co-senior author Michael Milone.

The researchers developed a receptor that displayed fragments of the autoantigen Dsg3, to which the B-cells that produce anti-Dsg3 antibodies are able to bind. Using a mouse model, they re-engineered the animal's T cells so that this receptor appeared on their surface.

This appeared to kill off Dsg3-specific B cells and prevented blistering in mice. "We were able to show that the treatment killed all the Dsg3-specific B cells, a proof of concept that this approach works," co-senior author Aimee Payne points out.

Other autoimmune diseases

Most importantly perhaps, there were no signs that the engineered T cells caused side effects by hitting the wrong cellular targets in the mice. Unlike other autoimmune disease therapies, patients' immune system was not weakened, and only the immune cells that caused the disease were destroyed.

Such a technology thus presents great potential for treating all the different types of autoimmune diseases. "If you can identify a specific marker of a B cell that you want to target, then in principle this strategy can work," Payne concludes.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.