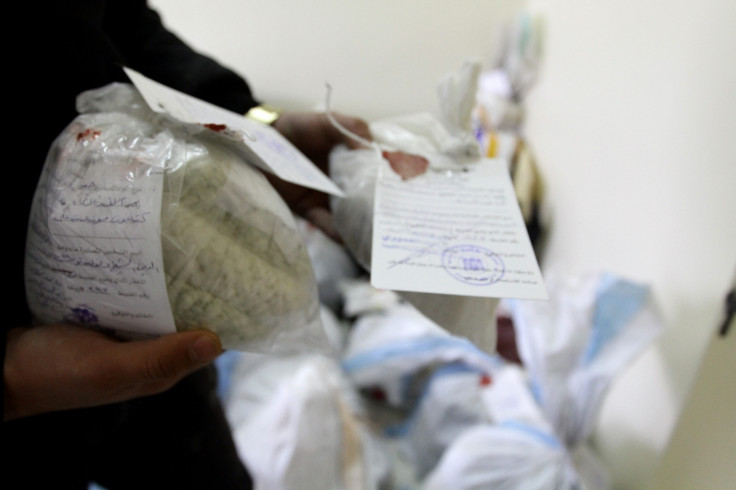

Captagon: Potent drug favoured by ISIS militants could be neutralised with a vaccine

Captagon is an amphetamine-like drug to promote alertness and morale.

Scientists have discovered what gives the 'pharmacoterrorism' drug Captagon its psychoactive potency, and how to mitigate its addictive properties in mice.

Captagon has been called the 'Jihad Pill' and is reportedly dubbed 'chemical courage' by ISIS. Its pharmacological name is fenethylline and was first invented in the 1960s to treat narcolepsy. It is highly addictive and can make its users a lot more alert, sometimes causing hallucinations and feelings of fearlessness.

It is widespread in the Middle East but is not often reported elsewhere. Aside from conflict zones such as Syria, about 40% of children and young adults aged 12 to 22 who use drugs in Saudi Arabia are addicted to Captagon.

In a study in the journal Nature, scientists characterised Captagon's mechanism of action. It is made of two substances, amphetamine and theophylline, a drug usually used to treat respiratory diseases. The theophylline acts synergistically with amphetamine, greatly amplifying the latter's strength.

"This combination greatly enhances amphetamine's psychoactive properties. So it now makes sense why it is so heavily abused," study author Kim Janda of the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, said at a press briefing.

The researchers honed in on the drug's mechanism by creating a vaccine for the various smaller chemical components of the drug. They tried these out one by one and in different combinations on mice, while measuring their activity levels, anxiety behaviours and whether they showed signs of reward from the components.

The drug showed similar effects to amphetamine but were much stronger. These findings make sense of the use of the drug to promote hypervigilance and morale among fighters, the researchers say.

The vaccines created in the experiments could be used to counteract the psychoactive and addictive effects of the drug, Janda said, although this was not the original intention of the research when they set out. Modification for human use is expected to take less than a year.

"If there's interest we could use this in humans. We would probably modify it to enhance [the vaccine's] properties," he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.