Chile's 'Penguins' Student Revolution Grows up [BLOG]

With four students elected to parliament, the battle for free education in Chile enters new era

Chileans went to the polls recently. In the presidential election the centre-left coalition candidate for Nueva Mayoria (New Majority) and former president Michelle Bachelet fell just short of the 50% needed to win in the first round. She will now face a run-off election against rightwing candidate Evelyn Matthei on 15 December, which Bachelet is expected to win. Perhaps the real story though was that four former high-profile student leaders, who had first risen to prominence in 2011 during mass student protests, were elected to congress in elections held the same day. Of the four, three of them - Camila Vallejo (The Guardian's Person of the Year in 2011), Giorgio Jackson and Karol Cariola were feature in Chile's Student Uprising, a documentary I am producing.

A question many have asked is why did some leaders from the combative student movement participate in electoral politics? In addition, now that these former leaders have been elected to congress, how has this been received by the wider student movement? To answer these two questions it is worth briefly putting the student protests into some kind of context.

Penguins against neoliberal education

Chile's privatised education system is just one part of wider neoliberal economic model that has been in place in Chile since 11 September, 1973, when the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende was overthrown by a US-sponsored military coup headed by Gen Augusto Pinochet. Under Pinochet and using state terrorism, a radical programme of neoliberal policies, including mass privatisation, was forced on the population. Thousands were murdered to bring "free markets" to Chile. It took 17 years before the Pinochet dictatorship finally came to an end and in 1990 formal democracy returned. However, the dictatorship's neoliberal economic model was largely continued by the country's new political elites.

A key feature of the model has been inequality: in Chile, the richest 0.01% of the population (around 1500 people) hold 10.1% of country's income. These inequities are also present in the educational system: less than 50% of students attend state funded schools, which are of poor quality and starved of funds. University education is not only one of the most expensive in Latin America but the world and is also starved of state funding. For instance, the University of Chile, the country's main university, only receives 14% of its budget from the state.

In 2006 there were attempts at reforming the system, after thousands of secondary school students took to the streets in what became known as the "Penguins' revolution" (in reference to the students' school uniform). While they managed to obtain some minor reforms of the education law created under Pinochet, their expectations of more profound reform were betrayed by a government and parliament dominated by centre-right political elites who had a vested interest in maintaining a profit-driven education system.

A protest to awaken consciousness

Broadly, this is the system that the current student current uprising has been challenging. Beginning in May 2011, student protests demanding free, quality state-funded education rocked Chile. Some 700 schools were occupied and daily protests took place during that year. One protest in August 2011 drew over half a million people in Chile's capital Santiago (with the population of Chile around 17 million, this would equate to nearly 1.9 million people out on the streets of London). The student protests have continued throughout 2012 and to a lesser degree in 2013.

When we asked Camila Vallejo, then president of the University of Chile Student Federation (FECh) and main spokesperson of the Confederation of Chilean Students (Confech), what the significance of the protests were, she argued that they had "served to awaken consciousness, and signalled a new horizon for Chilean society, in the direction of making profound changes to our country.."

Similarly for Giorgio Jackson, then president of the Catholic University of Chile Student Federation (FEUC) and also a Confech spokeperson, the protests have contributing to making Chileans "put aside the taboo and fears that existed in thinking of a different model" and have "delivered a clear and honest message to the public". "The people empathised with this message because it was not an invented one," he continued. "The reproduction of inequality and privilege exists in Chile and there is a generation that says 'no more'. The neoliberal model, the model of education as a consumer good has had 30 years to operate without restrictions. And it hasn't showed the benefits it promised. So now it's time that we Chileans change this model."

Changing society

As student leaders both Vallejo and Jackson, along with the student movement as a whole, have been very clear that it is not just the education system that has to change; it is the economic and political model to which it belongs that has to be transformed too.

Key to this is getting rid of the constitution enacted under Pinochet and that is still in place today. These unified demands have come from leaders with differing political traditions. Vallejo and Cariola are members of Chile's communist party, while Jackson had no ties to traditional political parties and represented a more liberal left perspective. Importantly, both of these have found a home in a broadbased movement characterised by its creativity and its ability reach out and work with other sectors of society such as trade unions and environmental groups.

By the end of 2011 Chile's political class were certainly on the defensive. As Karol Cariola, a former president of the University of Concepción Student Federation), put it to us: "The model is trembling and so are those who support the model." Throughout 2012 Chilean students continued to mobilise massive numbers to protests, facing heavy repression from Chile's security services.

As 2012 drew to a close there was a feeling that while the students had captured the nation's attention and energised demands for democratic renewal in Chile, ultimately the political class had not conceded significant ground to the students.

Friction in the movement

In 2013 Vallejo, Jackson and Cariola and three other former student leaders decided to run for congress in the hope of achieving change from within the system. They did so with the support of the coalition behind Bachelet's candidacy. Bachelet in turn seems to be making concessions to the students: free education at the primary, secondary and university level is one of her key campaign pledges.

However, the decision to run for office by Vallejo and the other former student leaders has proved controversial within some sectors of the student movement, not least because it was under Bachelet's first presidency from 2006-10 that secondary school students saw demands regarding education that sparked mass protests largely ignored.

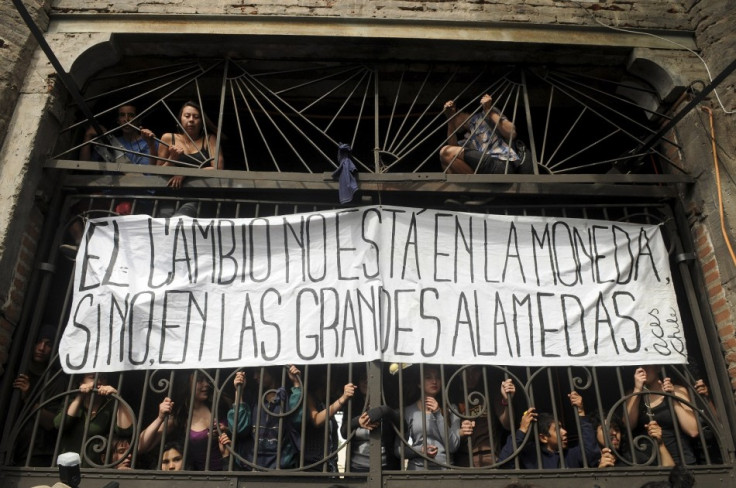

More generally the critique reflects a distrust in the institutional political process held not only from some student sectors but from the population as a whole. For example, on the day of the elections, Eloisa Gonzalez, spokesperson of the secondary school student body ACES and who has consistently argued against participating in elections, was part of a group of students that occupied Bachelet's campaign headquarters.

Similarly, Melissa Sepulveda, the new president of the Universidad de Chile's student federation, has said: "I wouldn't vote for Giorgio Jackson ... for Camila Vallejo neither. ..The possibility for change isn't in congress."

Despite this, Vallejo for one remains adamant that her position has not changed. In response to critics that have accused her of betraying the student movement she said shortly after winning her seat in congress that she continued believing in the same things she did when she was president of the University of Chile's student federation. No doubt the other former student leaders will say the same.

With a Bachelet presidential victory on the horizon, the challenge all the former student leaders face will be to spearhead a transformation of Chile's political system from within. The hopes of millions of Chileans, young and old, rest on their shoulders.

Pablo Navarrete is a British-Chilean journalist and documentary filmmaker. Chile Student Uprising will be released early in 2012. For more information on screenings and how you can support its production visit www.alborada.net/alboradafilms

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.