China: Heavily pregnant dinosaur-like reptile fossil discovered

The find is the first in its group – which includes dinosaurs – to have given birth to live young.

A fossil of a pregnant dinosaur-like reptile has been discovered, showing for the first time that archosauromorphs – the evolutionary group made up of dinosaurs, birds and crocodilians – didn't all lay eggs.

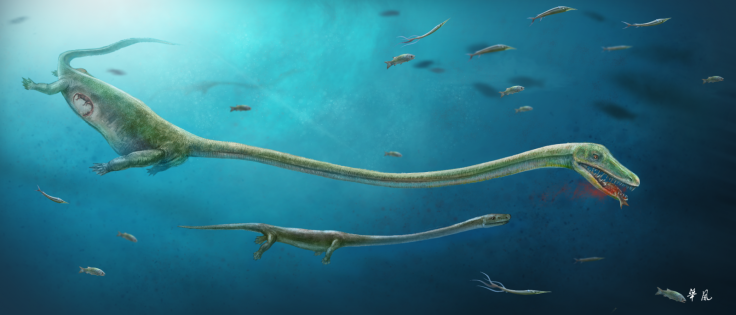

The reptile – called Dinocephalosaurus – lived in the seas around present-day south China. It had an extraordinarily long and thin neck, which stretched for about half its overall body length of about six metres. It lived during the Middle Triassic, about 245 million years ago.

The fossil discovered in southern China was one of just a handful of its species that have been found to date. The odds of finding a well-preserved fossil of Dinocephalosaurus that was about to give birth are extremely slim, the authors say.

The remains of a tiny reptile of the same species is well preserved inside the fossil's ribcage, with no signs of degradation from stomach acid. The smaller reptile – thought to be the embryo – is about 12% the size of the female.

It is the first example of a member of the archosauromorphs group found that is thought to have given birth to live young. This suggests there is no fundamental biological reason that dinosaurs or birds could not also have evolved to give birth to live young – it's just that, from the specimens found so far, it seems that they didn't, study author Mike Benton of the University of Bristol told IBTimes UK.

Baby, or 'food baby'?

Pregnancy isn't the only reason to have one small reptile inside a bigger one. One possibility to rule out was that the female Dinocephalosaurus had simply swallowed another reptile – a member of her own species – as her last meal.

"We were so excited when we first saw this embryonic specimen several years ago but we were not sure if the embryonic specimen is the last lunch of the mother or its unborn baby," said Jun Liu from Hefei University of Technology in China, also a study author, in a statement.

"Upon further preparation and closer inspection, we realised that something unusual has been discovered."

The reptile's extremely long, thin neck is one reason that the researchers think that the dinosaur is more likely to be a fossilised embryo than an example of cannibalism.

"The chances of being able to ingest a reasonably bulky reptile into a little mouth and down that long neck are pretty slender," Benton said.

Another clue was the orientation of the smaller reptile. The smaller animal was facing forwards, suggesting that it had not been swallowed headfirst. Marine mammals usually give birth to their live young tail-first, suggesting that Dinocephalosaurus had independently evolved a similar strategy.

"In the case of underwater animals, dolphins or whales, babies are born tail first, and so with a flick the baby rushes to the surface to get a gulp of air," Benton said.

The findings, published in a paper in the journal Nature Communications, open the door to the search for other archosauromorphs – including dinosaurs – that may also have given birth to live young.

Sea-dwelling archosauromorphs are the most likely targets for further examples of live birth, such as marine crocodiles in the Jurassic period, Benton said.

"Whether any dinosaur will be found with live birth – I've got no idea."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.