Day Zero is approaching, when Cape Town may become first global city to run out of water

Images of white South Africans scrounging for water sent sent ripples of shock through some sectors of society. But limited access to water is a fact of life for much of the country's population.

Cape Town is in the grips of an extended drought so severe that in a little over two months it may become the first ever global city to run out of water. At current rates of consumption, "Day Zero" is projected to arrive on 12 April, but some fear it could come sooner, while praying the rains arrive before that.

In an effort to hold off or delay total disaster, strict water rationing has been imposed on the city's four million residents. From Thursday 1 February, they will be allowed to use only 50 litres (13 US gallons) of water a day, down from the current 87-litre limit.

This measure – along with the introduction of three desalination plants and projects to tap groundwater – may be enough to make the city's water resources last until the rainy season. But if all fails and Day Zero does arrive, most of the city's taps will be cut off, and the security forces will be drafted in to guard collection points around the city, where people would have to queue for a daily ration of just 25 litres.

Only hospitals, key economic and industrial areas and densely populated areas with a higher risk of disease would be exempt from the water cut-off, said municipal authorities.

In St James, a charming upmarket suburb of Cape Town, long lines of residents have taken to queuing daily to collect water bubbling up from a natural spring. Images of white South Africans scrounging for water have sent ripples of shock through some sectors of society. But for many black people living in Cape Town's poorer areas, limited access to water is a fact of life. The only way they can get water is to carry buckets of it from communal taps to their shack dwellings.

Christine Colvin, senior manager of World Wildlife Fund (WWF)'s Fresh Water Programme in South Africa, told Reuters: "I think the prospect of Day Zero in a city of four million people is really frightening, because if Day Zero comes and nobody is prepared, there is going to be panic. There are other cities that have come very close during drought conditions to having no water - Sao Paulo in Brazil is one."

"This crisis will demand a whole of society approach, where we all pull together to get through this," the city said in a statement that acknowledged "panic" among residents fretting over the possible difficulties ahead. This weekend, Cape Town's water and sanitation department said it was investigating reports that some retailers might be illegally selling municipal tap water after people were seen lining up with empty bottles at two malls.

The water crisis is propelling Cape Town into the unknown, but the causes have been brewing for a while. Since around the end of white minority rule in 1994, the city's population has soared by 79 percent, while reservoir capacity only increased by 15 percent.

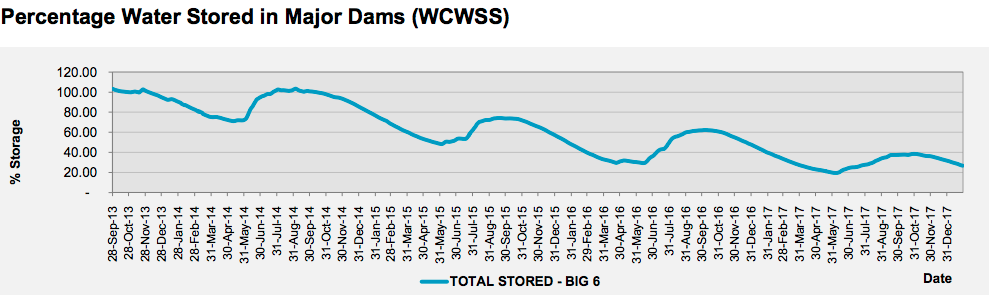

Meanwhile, the region has endured several years of drought. Research on long-term weather data done by the University of Cape Town found that the period from 2015-2017 has been the driest three-year period since 1933, and 2017 was the driest year since 1933, and possibly earlier, since comparable data before 1933 was not available. They say man-made global warming may have contributed to the severe weather, and that similar droughts could be more common in the future.

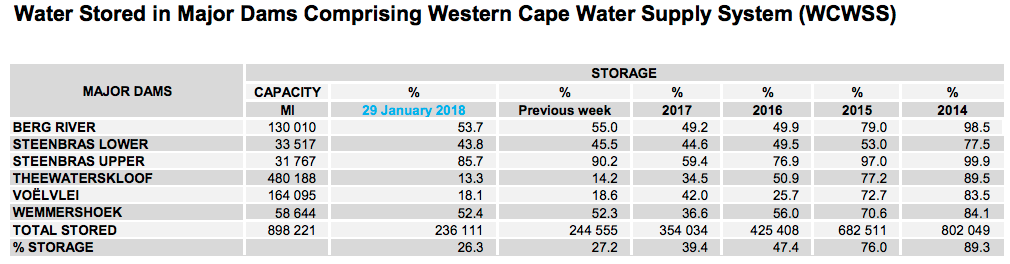

The average level of the reservoirs that are Cape Town's main water source is currently about 27 percent, but the final 10 percent is considered unusable because of mud, weeds and debris at the bottom. Some residents are already complaining that silt in tap water makes it undrinkable. The city says it would have to turn off most taps if the average reservoir level falls below 13.5 percent.

Theewaterskloof Dam, whose reservoir was once the city's biggest provider, is a startling sight. The dam resembles a desert-like, arid piece of land, with hardly any water.

The City of Cape Town authorities publish a daily update of the levels in the city's six main reservoirs, making the data available online for residents. Yesterday's figures showed that Theewaterskloof was 14.2% full. Today it is 13.3%, dangerously close to the 10% cut-off point.

@DaveWallsworth @British_Airways Dave, you were kind enough to retweet some film of Theewaterskloof dam which supplies Cape Town. I filmed it again today and it’s terrifying. Your involvement spread the word incredibly. People need to save water now! Thank you. #dayzero #basmart pic.twitter.com/Nd3bj4mkBF

— Alistair Coy (@alistaircoy) January 28, 2018

South Africa's tourism industry is taking a hit. Agencies have reported cancellations from domestic and international travellers, said Cape Town Tourism CEO Enver Duminy, according to the African News Agency. While tourists are still welcome, tourism authorities urge them to flush the toilet as little as possible and "take a dip in the ocean instead of swimming pools, and maybe even spare yourself a shower."

Helen Zille, the Premier of Western Cape province, said there is still time to avert "Day Zero" if everyone used 50 litres or fewer a day. For now, Cape Town residents are advised to limit showers to fewer than 90 seconds and to use a bucket to collect the runoff and use that to flush the toilet.

In a Facebook post, she offered some suggestions on how to save water. "Turn off the tap of your toilet cistern and use all of the grey water in your house from washing, save it, and put it into your toilet cistern", she said. "No-one should be showering more than twice a week at this stage. You need to save water as if your life depends on it, because it does." Last year, she revealed that she showered once every three days.